By Lesley Batten and Claire Minton

Learning outcomes

Reading and reflecting on this article will enable you to:

- gain an understanding of the current knowledge of the physiology of sleep and its association with illness and healing

- consider steps to enhance patient sleep, including identifying poor sleep quality and advising patients on steps they can take to improve their sleep, and considering the institutional environment for sleep, therefore potentially improving health outcomes.

Reading this article and completing this ‘Appeared to sleep well’: How much sleep has your patient had and why does it matter? self-assessment learning activity is equivalent to 60 minutes of professional development.

NCNZ competencies addressed: Registered Nurse competencies: 1.4, 1.5, 2.1-2.4, 2.6,

2.8-2.9, 3.2, 4.1-4.3

Introduction

Of one thing you may be certain, that anything which wakes a patient suddenly out of his sleep will invariably put him into a state of greater excitement, do him more serious, aye, and lasting mischief, than any continuous noise, however loud.

(Florence Nightingale1, 1860, p. 44)

Sleep is defined as the “temporary state of relative unconsciousness from which an individual can be roused either by internal or external stimuli”2

(p. 105).

Since Florence Nightingale’s time1, nurses have recognised the importance of sleep to patients’ recuperation and wellbeing as well as nurses’ capacity to support patients’ sleep. Patients experiencing sleep deprivation or fragmented sleep develop complex physiological reactions that, with their other health conditions, result in poorer health outcomes, including increased hospital stays and delirium. However, nurses often rely on their own observations to assess sleep quality – an inherently unreliable process.

In this article we provide an overview of current understanding of the impact of sleep and sleep deprivation on recuperation for adults in institutional settings and argue for a whole-of-system approach to ensure that environments where patients sleep best meet their needs.

While we particularly mention sleep in institutional settings such as hospitals, the information is relevant for nurses working with patients in all areas and for nurses themselves, especially those who undertake shift work. We do not address the many sleep disorders in this article.

Sleep

Mrs Brown, aged 72, admitted today with a #NOF following a fall at home. While awaiting surgery, she is in traction in a six-bedded bay, with a PCA for analgesia. She usually cares for her husband who has mild dementia, and states that she sleeps lightly at home.

When Mrs Brown reports feeling exhausted the next day, what factors would you consider? What, if anything, could you change?

Sleep is a complex phenomenon and is vital for many bodily functions. Two processes are involved in sleep regulation: a homeostatic component of sleep pressure after periods of wakefulness, and circadian influences via the circadian body clock. The circadian body clock regulates all circadian rhythms including the sleep-wake cycle – periods of sleep and wakefulness over a period of approximately 24 hours2,3. Sleep patterns differ throughout life stages and change with ageing processes.

Normal sleep involves a sequence of complex physiological states controlled by the central nervous system (CNS) and associated with changes in many body systems. Sleep is a cyclical process with distinct physiological responses over the course of the sleep cycle.

There are two sleep states:

- Non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep (approximately 75% of sleep time).

- Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep (approximately 25 per cent of sleep time).

NREM sleep includes three stages N1–3, progressing from light to increasingly deeper sleep, when it becomes increasingly more difficult to rouse a person3,4.

REM sleep occurs at the end of these stages, and usually gets longer throughout the total sleep period.

Each full sleep cycle ranges from approximately 70 to 120 minutes, with an average of 90 minutes, and most adults have about five cycles over an eight-hour sleep with some brief awakenings between cycles. While asleep, the body undergoes processes of physiological and psychological conservation and restoration.

During NREM sleep stages, parasympathetic activity increases, sympathetic tone decreases and the release of human growth hormone aids epithelial and cell repair, while skeletal muscles relax, allowing the conservation of chemical energy for cellular processes. The basal metabolic rate falls, heart rate, breathing rate, muscle tone, core temperature and blood pressure all decrease.

REM sleep is important for cognitive restoration and is associated with changes in cerebral blood flow, increased cortical activity, increased oxygen consumption and cortisol release with alterations in heart rate, temperature, blood pressure and breathing rate. Most muscles become atonic during REM sleep. Increased cerebral blood flow is thought to aid memory storage, learning and concentration2.

All sleep stages are important to health; however, when unwell and in an unusual environment such as a hospital ward, individuals’ sleep patterns change in multiple ways, including with reduced sleep depth, increased sleep fragmentation, including more arousals, awakenings and limited REM sleep. A list of the factors that may disrupt a patient’s sleep cycle is included in Box 1.

Inadequate sleep – its effects

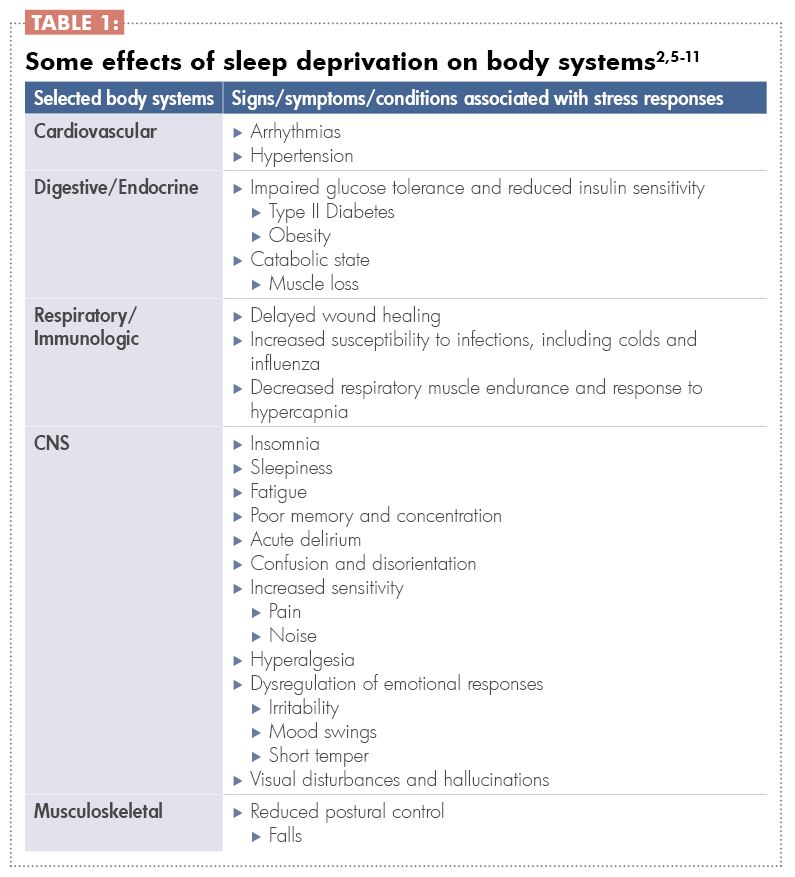

Sleep deprivation, either acute or chronic, causes a stress response that disrupts the key hormone release cycles normally linked to circadian rhythms, including the early evening melatonin release, the late-night release of growth hormone and the peak of cortisol release soon before waking naturally2 (see Table 1).

These effects of sleep deprivation and the stress response combine to contribute to poor health outcomes. Those outcomes include increased length of hospital stay, increased morbidity including nosocomial infections, and hospital-acquired injuries such as pressure injuries, poor wound healing, and mortality2,5,7. Specifically for hospitalised elders, these outcomes increase the risk of needing residential care post-discharge9.

Modifying the sleep environment

As shown in Box 1, many factors impact on sleep, and some are potentially modifiable by either the individual or the institution.

Research findings about sleep quality are consistent, with around 30 per cent of hospital patients reporting unsatisfactory sleep12. Firstly, patients’ sleep is often disrupted. In one study9, patients woke about 13 times per night. Secondly, sleep duration is short – about 3.75 hours per night in one study9. Thirdly, disruptions often mean that patients are woken mid-sleep cycle (of about 90 minutes).

There is the potential for patients to then experience disorientation (sleep inertia), depending on the stage of sleep from which they were awoken, the amount of sleep that they have had and the time of day they are woken13. Patients attempt to catch up on sleep during the day but this is largely unsuccessful6. However, research findings about other factors are more nuanced and contextual, such as the impacts of light and type of noise on sleep, the differences between sleeping in a single or multi-bed room, and even how much the hospital bed affects sleep9,14.

There is, however, much interest in how the environment can be modified and a number of approaches are being tested internationally. While many single approaches, such as ‘quiet times’ are tried, the most successful approaches are those that are whole-of-system, including consideration and management of all the work and of all the staff who affect what happens at night time in a ward or unit14. Successful approaches include a combination of the following activities:

- Agreed ‘quiet times’ when disturbances are limited and routine care activities are put on hold if possible. Those times are usually between 10pm and 6am.

- Lights automatically dimmed corresponding with quiet times.

- Shifting of the times for ‘routine’ cares and vital signs recording throughout the 24-hour period to limit disruptions at night.

- Reducing the prescription of medications given during quiet times, or shifting the times for administration (e.g. intravenous antibiotics).

- Limiting the administration of medications known to inhibit or impact on sleep to earlier in the day.

- Monitoring noise in corridors, with warning lights when a threshold is breached.

- Assessment and care planning so that patients who want to settle first at night are settled first.

- A night-time routine, including quiet music, lights gradually dimming.

- Care with the use of sedatives.

- Grouping of cares overnight 9,10,14.

Personalising sleep interventions

Individualised approaches to promoting sleep have also been researched. Interestingly, while individual patients may respond positively to these approaches, the evidence is quite weak and more research is needed11. The current evidence is strongest for massage, acupuncture, music, and natural sounds 5,11, and weak for ‘sleep hygiene’ (good sleep habits) and relaxation approaches11. However, there is also the opportunity for hospitalised patients to receive information at this time to aid their sleep at home.

Assessing sleep

Considering how important sleep is to healing and recuperation, attention to assessment of a patient’s sleep pattern is important. While sleep measurement is complex and reliant on tools such as EEG, sleep assessment includes understanding the person’s baseline sleep pattern and how the patient perceives their own sleep quality, questions about which are included in every nursing assessment. Standardised sleep assessment tools that are often only used in research could be used in everyday clinical practice12. These tools could replace nurses’ perceptions that are the most common assessment method. Nurses’ perceptions are highly unreliable, with nurses overestimating the perceived sleep quality8,12,15. It also results in the ‘appeared to sleep well’ record commonly seen in clinical notes.

One easy-to-use tool that, to date, has been mainly used in critical care units, the Richards-Campbell Sleep Questionnaire, includes five separate line measures of:

- Sleep depth (light-deep)

- Sleep latency (delay in falling asleep – fell asleep almost immediately)

- Awakenings (awake all night – awake very little)

Returning to sleep (when woken or waking, couldn’t get back to sleep – got back to sleep immediately)

Sleep quality (a bad night’s sleep – a good night’s sleep).

When used in research, another question is added related to the noise level in the environment15. Importantly, this tool requires patient self-report and is therefore a more valid measure of sleep.

Conclusion

The impacts of restful sleep cannot be overestimated and nurses are in a unique position to both monitor and promote sleep in institutional settings and to also support individuals at home. Patients who experience sleep deprivation exhibit poorer health outcomes, some of which are preventable, and identifying poor sleep and its causes are important steps in improving sleep health. There is much potential in a multi-pronged approach to modifying the sleep environment, combined with better use of assessment tools.

Download the learning activity here >>

Box 1:

What affects a patient’s sleep?

The individual, their health condition and responses

- Their normal sleep pattern.

- Current condition.

- Co-morbidities.

- Pain and discomfort.

- Anxiety.

- Pre-existing sleep disorders, such as apnoea.

- Age.

- Cultural needs, including whether sleeping in an environment with strangers or with

- people of other genders is appropriate.

Therapies

- Medications (e.g. steroids, diuretics).

- Indwelling devices (e.g. catheters, IV devices).

- Equipment (alarms, mechanical noises).

- Care interventions.

Environment

- Temperature, such as air-conditioned rooms.

- Noise.

- Disturbances.

- New environments, including hospital beds.

- Light.

- Presence of others in single or multi-bed rooms.

About the authors:

- Lesley Batten RN PhD is a senior researcher at Massey University, Palmerston North.

- Claire Minton RN MN is a lecturer and PhD candidate at Massey University, Palmerston North.

This article was peer reviewed by:

- Sally Powell RN MHSc (Clinical), a clinical nurse specialist in sleep health at Canterbury District Health Board’s Sleep Unit.

- Karyn O’Keeffe PhD, a research fellow and sleep physiologist at the Sleep/Wake Research Centre, Massey University.

Recommended resources

- The Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre website provides self-help information for patients about how to improve their sleep during their hospital stay: www.mskcc.org/cancer-care/patient-education/improving-your-sleep-during-your-hospital-stay.

- The Australasian Sleep Association has resources for health professionals on sleep disorders: www.sleep.org.au/professional-resources/health-professionals-information.

- The Sleep Health Foundation Australia has resources for patients and health professionals on sleep health and sleep disorders and their management:

www.sleephealthfoundation.org.au.

References:

- NIGHTINGALE F (1860). Notes on nursing. Appleton & Company. Accessed 7 April 2017 from http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/nightingale/nursing/nursing.html

- CRAFT J, GORDON C, HUETHER S, MCCANCE K, BRASHERS V, & ROTE N (2015). Understanding pathophysiology. Mosby: Sydney.

- SCHWARTZ JRL, & ROTH T (2008). Neurophysiology of sleep and wakefulness: Basic science and clinical implications. Neuropharmacology 6, 367-378.

- SILBER, MH (2012). Staging sleep. Sleep Medicine Clinics 7 (3) 487-496.

- SU C-P, LAI H-L, CHANG E-T, YIIN L-M, PERNG S-J, CHEN P-W (2012) A randomized controlled trial of the effects of listening to non-commercial music on quality of nocturnal sleep and relaxation indices in patients in medical intensive care unit. Journal of Advanced Nursing 69(6). doi: 10.111/j.1365-2648.2012.06130.x

- PULAK L, & JENSEN L (2016) Sleep in the intensive care unit: A review. Journal of Intensive Care Medicine 31(1) 14-23. Doi 10.1177/0885066614538749

- RADTKE K, OBERMANN K, & TEYMER L (2014). Nursing knowledge of physiological and psychological outcomes related to patient sleep deprivation in the acute care setting. MEDSURG Nursing 23(3) 178-184.

- RITMALA-CASTREN M, LAKANMAA R, VIRTANEN I, & LEINO-KILPI H (2014). Evaluating adult patients’ sleep: An integrative literature review in critical care. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 28, 435-448. doi: 10.1111/scs.12072

- MISSILDINE K, BERGSTROM N, MEININGER J, RICHARDS K, & FOREMAN M (2010). Sleep in hospitalised elders: A pilot study. Geriatric Nursing 31(4) 263-271.

- BARTICK M, THAI X, SCHMIDT T, ALTAYE A,

& SOLET J (2010). Decrease in as-needed sedative use by limiting night time sleep disruptions from hospital staff. Journal of Hospital Medicine 5(3) E20-E24. doi; 10.1002/jhm.549 - HELLSTRÖM A, FAGERSTRÖM C, & WILLMAN A (2011). Promoting sleep by nursing interventions in health care settings: A systematic review. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing 128-142. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2010.00203.x

H - OEY L, FULBROOK P, & DOUGLAS J (2014).

Sleep assessment of hospitalised patients: A literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies 51, 1281-1288 http://dx.doi.org/10.1061/j.ijnurstu.2014.02.001 - TROTTI LM (2016). Waking up is the hardest thing I do all day: Sleep inertia and sleep drunkenness. Sleep Medicine Reviews http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2016.08.005

- FILLARY J, CHAPLIN H, JONES G, THOMPSON A, HOLME A, & WILSON P (2015). Noise at night in hospital general wards: A mapping of the literature. British Journal of Nursing 24(10) 536-540.

- KAMDAR B, SHAH P, KING L, KHO M, ZHOU X, COLANTUONI E, COLLOP N, & NEEDHAM D (2012). Patient-nurse interrater reliability and agreement of the Richards-Campbell sleep questionnaire. American Journal of Critical Care 21(4) 261-269, doi: 10.4037/ajcc2012111

- NURSING COUNCIL OF NEW ZEALAND (2010, amended 2016) Competencies for registered nurses. Retrieved May 2017 from www.nursingcouncil.org.nz/Publications/Standards-and-guidelines-for-nurses.