Health and Disability Commissioner Anthony Hill has found the Waikato District Health Board failed to provide adequate care to a 78-year-old man during his hospital admission, which occurred in 2013.

The man had lived at home with his wife and been active and mobile, although he suffered from emphysema. He was admitted to the emergency department at 10.36am on a Friday after falling over at home and was diagnosed with a displaced left neck of femur fracture.

The orthopaedic surgeon on that day decided an acute total hip joint replacement was needed and anticipated he would be operated on later that day. However, at 6pm the surgeon finished for the day and handed over to another consultant orthopaedic surgeon.

The man was due for surgery on Saturday, but at 8am the surgeon decided it was better to defer it until Monday, despite the optimal time frame for such acute surgery being no more than 48 hours.

The first doctor said surgery was delayed because there were others more in need of an operation. The second surgeon said there were no dedicated orthopaedic theatres available over the weekend and that it was best to wait until a weekday when staffing levels were higher and he could be better looked after.

In the evening of his fifth day in hospital, a Tuesday, he finally had the operation.

The day after surgery (day six) the man began to deteriorate and when his Adult Deterioration Detection System (ADDS) score reached four that afternoon the nursing staff contacted a house officer. The man’s ADDS continued to fluctuate that night between 3 and 7 and he was reviewed by a house officer but a senior medical officer was not called.

The man improved during the daytime hours of day 7 (an ADDS score of 0-1) but then deteriorated that evening, rising to 4 and then to 11 at 10.30pm and leading to an intensive care review and admission to a High Dependency Unit. The man died on his 13th day in hospital.

Hill said the hospital had a policy that a senior medical officer should be contacted if a patient deteriorated rapidly, as the man did between day 6 and 7 of his hospital admission, but that did not happen.

Hill said the case highlighted particular hospital systems issues that contributed to the provision of suboptimal care: in particular, the delay in carrying out the surgery was more than double the optimal timeframe for such surgery, and a failure to escalate appropriately to senior staff, in accordance with DHB policy, when the man deteriorated post-operatively.

As a result, it was found that the DHB failed to provide services to the man with reasonable care and skill, Hill said.

He recommended that the DHB report back to him on the effect of the key changes it had made to its services on acute orthopaedic waiting times and quality of patient care.

The changes made by the DHB since the incident in 2013 included dedicated orthopaedic operating theatres, an acute escalation process, orthopaedic service subspecialising, and an integrated orthogeriatric service.

Hill also recommended that the DHB conducts a scheduled audit of the standard of care provided to acute patients with hip fractures, based on the Australian and New Zealand Guideline for Hip Fracture Care, and provides evidence of an up-to-date audit of staff compliance with the application of DHB policy, including the recognition of the deteriorating patient and the escalation of care to senior staff.

Source: New Zealand Herald with additional reporting by Nursing Review from HDC report

]]>A great deal of research in recent years has focused on the benefits of mobilising all patients as soon as possible after surgery. Mobilising after hip or knee replacement surgery (lower limb arthroplasty or LLA), however, has traditionally been delayed. But advancements in surgical and anaesthetic technique mean it is now not only safe to mobilise these patients earlier, but there is also evidence that there are many benefits in doing so.

Background

Arthrosis – the degeneration of a joint most commonly caused by osteoarthritis – is the leading reason for having joint replacement surgery or arthroplasty. Arthrosis is debilitating, often causing pain and disability and substantially reducing the quality of life of those affected.

The first attempts at joint replacement surgery happened more than 100 years ago, but only became effective in the 1960s (1,2). Hip and knee replacements (LLA) have become more common in the last two decades and, with our ageing population, demand will continue to grow (it is estimated that arthrosis affects 75 per cent of people over 65).

To meet this growing demand, researchers are looking at ways to reduce costs. Traditionally, LLA patients spent extended periods of time recovering in hospital. While length of stay has reduced for all types of surgery in the past 10 years, there is still a huge variability in length of stay globally after LLA, with ranges of 1–21 days (4).

A number of enhanced recovery programmes (ERPs) – also known as enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) or ‘fast track’ protocols – have gained popularity in Europe and the US, with beneficial results for both LLA patients and providers (5). Many ERPs are expensive to implement, however, with entire units set up with increased staffing and equipment.

But while researching the barriers and opportunities for LLA patients in my own hospital (as part of a nursing research methods paper), I found one key component of many ERPs that I felt could be hugely beneficial as a stand-alone change: mobilising LLA patients on the day of surgery, not the day after. This became the focus of my master’s degree research. (Mobilising the day after surgery, i.e. day one, was standard when I began the study. See sidebar 1 for a summary of literature review findings on the benefits of early mobilisation of LLA patients.)

Introducing day of surgery mobilisation

Like many idealistic students, I wanted to carry out a randomised controlled trial to compare outcomes between day of surgery and day one mobilisers. However, my literature review revealed so many benefits in mobilising early, that I decided it would be unethical to make some patients stay in bed and not have the opportunity to benefit.

So, with the support of our surgeons and management at my 38-bed private surgical hospital in New Plymouth, I introduced an early mobilisation initiative for LLA patients as a quality improvement project. The initiative included developing a checklist so nurses could be confident that their patients were safe to mobilise (see checklist box). Three months later, after receiving ethics consent, I audited the discharged patient files for my master’s thesis and compared the outcomes of early mobilised LLA patients with the outcomes of patients mobilised on day one.

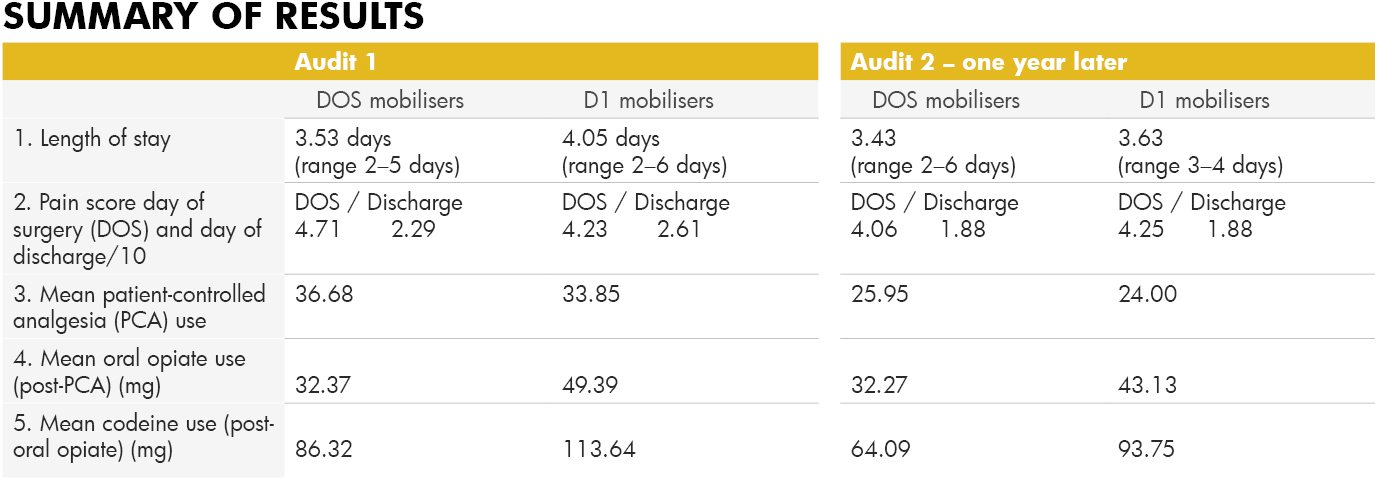

Exactly a year after the first audit, I conducted a follow-up audit. This was partly because uptake of the idea at the beginning was relatively slow, but gained support over the year as nurses and surgeons saw the benefits to patients. I also wanted to ensure that the gains were sustained (see sidebar 2 for audit results).

Conclusion

Many nurses were initially sceptical about mobilising LLA patients on the same day as their surgery. But the initiative soon gathered momentum when nurses saw for themselves their patients gaining independence earlier, with less pain and fewer adverse effects post-surgery.

This change of heart was reflected in the audit results with only 56 per cent of LLA patients being mobilised successfully on the day of surgery in the first audit, compared with 84.6 per cent a year later.

While pain scores on the day of surgery were slightly higher on the day of surgery for early mobilisers, by the day of discharge their scores were lower, and less pain relief was used by early mobilisers during their stay, indicating lower pain levels. The length of stay decreased after the initiative and continued to decrease in the follow-up. Early mobilisation after LLA has now become the norm at our hospital as we continue to see improved outcomes for these patients.

*Author: Diane Alder Is a registered nurse at New Plymouth’s Southern Cross Hospital and completed a Master of Health Sciences degree last year.

Sidebar 1:

The benefits of early mobilisation of LLA patients

-

Less risk of venous-thromboembolism (VTE)

Patients mobilised the day of surgery are 30 times less likely to suffer from VTE complications (6).

-

Less pain

A number of studies show early mobilisers state lower pain scores overall (7,8,9). And the benefit isn’t just short-term; a German study found their early mobilisation group stopped taking analgesia altogether by day 41, while the traditional day one mobilisers continued to take analgesia for a further 30 days (10).

-

Less opiate pain relief required

Lower pain scores means less pain relief. One study showed a 60 per cent reduction in opiate use in the early mobilising group (6). Less opiate medication means a reduction in side effects, such as nausea and vomiting, so a reduced need for anti-emetics.

-

Less syncope

Often cited as a reason not to mobilise on the day of surgery, the risk of syncope is actually less likely to occur (6). Judicial intravenous fluid replacement and good pre-mobilising assessment is, of course, important.

-

Fewer blood transfusions

Fear of increased blood loss is also cited as a reason not to mobilise but early mobilisers actually have less need for blood transfusions – 9.8 per cent compared with 23 per cent (6,11).

-

Less joint stiffness

Joint stiffness can be associated with chronic pain following LLA. A Danish researcher found that early and intensive mobilisation helped to avoid the development of specific knee arthroplasty complications such as prolonged stiffness and delays in recovery of strength (12, 13).

-

Less mortality

Several large studies show that mortality reduces with ERPs that include early mobilisation (11,14,15).

-

Less time in hospital

Fifteen recent studies showed a reduced length of stay with ERPs; five of the studies isolated early mobilisation and studied its effect on length of stay. Results varied but 100 per cent had reduced length of stay for early mobilisers.

-

Increased quality of life/satisfaction

Most patients would prefer to be home, back to work or back to the golf course as soon as possible. A Danish study showed early mobilisers had increased quality of life/satisfaction (16).

-

Fewer infections

Many studies show shorter lengths of stay mean fewer infections, (8, 10, 17, 18). If a patient is able to mobilise to the toilet within hours of having LLA surgery, there is no need for an indwelling urinary catheter, removing the risk of catheter-induced UTIs. The less time a patient is in bed, the less chance of orthostatic pneumonia. And less time in hospital means a reduced likelihood of a hospital-acquired infection.

-

Fewer re-admissions

Early opponents to fast-track protocols argued that, if discharged too early, patients would just return as re-admissions. In fact, patients who mobilise earlier are far less likely to be re-admitted (4,19).

-

Economic benefits

There are huge savings to be made with reduced length of stay. Several studies have researched the economic benefits, citing savings of US$454,000 per annum in just one hospital in the US (20), €3.5 million in total per annum in Denmark (15), and £141 million in total per annum in the UK (11).

Side bar 2:

Early mobilisation New Zealand clinical audit

Audit 1: December 2015, following the introduction of an early mobilisation initiative for LLA patients in September 2015.

Subjects: n=52 (pre-initiative) + n=52 (post-initiative) = 104 patients, split into two groups; those that mobilised day of surgery (DOS) n=38; and those that mobilised day one (D1) n=66. Age range of patients was 51–92 years.

Audit 2: Follow-up audit. December 2016, one year later.

Subjects: n= 52, divided into DOS mobilisers n=44 and D1 mobilisers n=8.

Safety criteria checklist for early mobilisation

1. Patient is haemodynamically stable

● Blood pressure is stable, with systolic ≥ 100

● Heart rate is stable ≤ 100bpm

● Bleeding is minimal-moderate, if drain used then ≤ 50ml/hour

● Patient is not light-headed or short of breath at rest

2. Patient is neurovascularly stable

● Patient can actively plantar and dorsi flex ankles of both feet

● Patient can actively contract both quadriceps (doesn’t necessarily have to lift leg actively)

● Sensation can be reduced in operated leg, but not absent

3. Patient consent

Patient is alert and oriented and able to consent to mobilising

● Pain is controlled to level considered acceptable to patient at rest

REFERENCE LIST

- Wroblewski, B. M., Siney, P. D., & Fleming, P. A. (2006). The charnley hip replacement: 43 years of clinical success. Acta Chirurgiae Orthopaedicae et Traumatologiae Cechoslovaca, 73(1), 6-9.

- Mont, M., Jacobs, J., Lieberman, J., Parvizi, J., Lachiewicz, P., Johanson, N., & Watters, W. (2012). Preventing venous thromboembolic disease in patients undergoing elective hip and knee arthroplasty. (2011). The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 19(12), 768.

- Lilikakis, A. K., Gillespie, B., & Villar, R. N. (2008). The benefit of modified rehabilitation and minimally invasive techniques in total hip replacement. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, 90(5), 406-411. doi:10.1308/003588408X285900

- Stambough, J. B., Nunley, R. M., Curry, M. C., Steger-May, K., & Clohisy, J. C. (2015). Rapid recovery protocols for primary total hip arthroplasty can safely reduce length of stay without increasing readmissions. The Journal of Arthroplasty, 30(4), 521-526. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2015.01.023

- Bandholm, T., & Kehlet, H. (2012). Physiotherapy exercise after fast- track total hip and knee arthroplasty: Time for reconsideration? Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 93(7), 1292-1294. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2012.02.014

- Pearse, E. O., Caldwell, B. F., Lockwood, R. J., & Hollard, J. (2007). Early mobilisation after conventional knee replacement may reduce the risk of post-operative venous thromboembolism. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery-British Volume, 89B(3), 316-322. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.89B3.18196

- Lunn, T. H., Kristensen, B. B., Gaarn-Larsen, L., & Kehlet, H. (2012). Possible effects of mobilisation on acute post-operative pain and nociceptive function after total knee arthroplasty. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica, 56(10), 1234-1240. doi:10.1111/j.1399-6576.2012.02744.x

- Labraca, N. S., Castro-Sanchez, A., Mataran-Penarrocha, G., Arroyo-Morales, M., Sanchez-Joya, M., & Moreno-Lorenzo, C. (2011). Benefits of starting rehabilitation within 24 hours of primary total knee arthroplasty: Randomized clinical trial. Clinical Rehabilitation, 25(6), 557-566. doi:10.1177/0269215510393759

- Raphael, M., Jaeger, M., & van Vlymen, J. (2011). Easily adoptable total joint arthroplasty programme allows discharge home in two days. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia-Journal Canadien d Anesthesie, 58(10), 902-910. doi:10.1007/s12630-011-9565-8

- den Hertog, A., Gliesche, K., Timm, J., Muhlbauer, B., & Zebowski, S. (2012). Pathway-controlled fast-track rehabilitation after total knee arthroplasty: A randomized prospective clinical study evaluating the recovery pattern, drug consumption, and length of stay. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery, 32(8), 1153-1163. doi:10.1007/s00402-012-1528-1

- Malviya, A., Martin, K., Harper, I., Muller, S. D., Emmerson, K. P., Partington, P. F., & Reed, M. R. (2011). Enhanced recovery programme for hip and knee replacement reduces death rate: A study of 4,500 consecutive primary hip and knee replacements. Acta Orthopaedica, 82(5), 577-581. doi:10.3109/17453674.2011.618911

- Holm, B., Kristensen, M. T., Myhrmann, L., Husted, H., Andersen, L. O., Kristensen, B., & Kehlet, H. (2010). The role of pain for early rehabilitation in fast track total knee arthroplasty. Disability and Rehabilitation, 32(4), 300-306. doi:10.3109/09638280903095965

- Husted, H., Jørgensen, C. C., Gromov, K., & Troelsen, A. (2015). Low manipulation prevalence following fast-track total knee arthroplasty: A multicenter cohort study involving 3,145 consecutive unselected patients. Acta Orthopaedica, 86(1), 86-91.

- Savaridas, T., Serrano-Pedraza, I., Khan, S. K., Martin, K., Malviya, A., & Reed, M. R. (2013). Reduced medium-term mortality following primary total hip and knee arthroplasty with an enhanced recovery programme: A study of 4,500 consecutive procedures. Acta Orthopaedica, 84(1), 40-43. doi:10.3109/17453674.2013.771298

- Khan, S. K., Malviya, A., Muller, S. D., Carluke, I., Partington, P. F., Emmerson, K. P., & Reed, M. R. (2014). Reduced short-term complications and mortality following enhanced recovery primary hip and knee arthroplasty: Results from 6,000 consecutive procedures. Acta Orthopaedica, 85(1), 26-31. doi:10.3109/17453674.2013.874925

- Larsen, K., Sorensen, O. G., Hansen, T. B., Thomsen, P. B., & Søballe, K. (2008). Accelerated perioperative care and rehabilitation intervention for hip and knee replacement is effective: A randomized clinical trial involving 87 patients with 3 months of follow-up. (2008). Acta Orthopaedica, 79(2), 149-159. doi:10.1080/17453670710014923

- Tayrose, G., Newman, D., Slover, J., Jaffe, F., Hunter, T., & Bosco, J. (2013). Rapid mobilization decreases length-of-stay in joint replacement patients. Bulletin of the NYU Hospital for Joint Diseases, 71(3), 222-226.

- Wellman, S. S., Murphy, A. C., Gulcynski, D., & Murphy, S. B. (2011). Implementation of an accelerated mobilization protocol following primary total hip arthroplasty: Impact on length of stay and disposition. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine, 4(3), 84-90. doi:10.1007/s12178-011-9091-x

- Robbins, C. E., Casey D., Bono, J. V., Murphy, S. B., Talmo, C. T., & Ward, D. M. (2014). A multidisciplinary total hip arthroplasty protocol with accelerated postoperative rehabilitation: does the patient benefit? The American Journal of Orthopedics, 43(4), 178-181.

- Chen, A. F., Stewart, M. K., Heyl, A. E., & Klatt, B. A. (2012). Effect of immediate postoperative physical therapy on length of stay for total joint arthroplasty patients. Journal of Arthroplasty, 27(6), 851-856. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2012.01.011

The announcement of an extra $6.5m for the adult cochlear implant programme came just over a week after an online petition by 22-year-old Danielle Mackay, signed by 26,643 people, was presented to Parliament by the country’s first deaf MP Mojo Mathers. The petition called for the Government to increase funding so Mackay could receive cochlear implant surgery before she lost her hearing.

Health Minister Jonathan Coleman said that in 2013 the number of funded cochlear implants for adults increased from 20 to 40 a year and the latest announcement meant that 100 implants could be funded this financial year. The money is to come from “reprioritisation” within Vote Health.

]]>

Building work will begin this year and the expansion is expected to be completed by next winter, allowing nearly 100 additional complex surgeries per year. The unit currently has around 1,500 ICU admissions each – more than half from other DHBs around the lower North Island and upper South Island.

]]>

Name: Sue Clynes

Job title: OR nurse/Maxillofacial team leader

Location: Onboard the Africa Mercy

5.45 AM Wake:

My alarm chirps and I quickly turn it off before it disturbs my husband John. I like to get up and spend some time in prayer before I start my day. I then shower, get dressed, and head up to breakfast with my husband and friends in the dining room. I live on board the Africa Mercy, which is a hospital ship giving free operations to the poorest of the poor.

At the time of writing this, we are working in Madagascar. Approximately 450 people from all around the world are living on board so mealtimes are interesting and fun. After breakfast I head back to my cabin, take my antimalarial tablet, clean my teeth, put my hat on and leave for work, which takes me about 30 seconds as I just have to walk down one staircase.

7.45 AM Start work

I like to get to work before everyone else so I can call into the ward and introduce myself to the patients and get the theatre set up in plenty of time. I turn the bed warmer on, and check the theatre lights and the suction unit. By then other nurses start to arrive so I can start to delegate tasks like fetching local anaesthetic and saline. Most staff are experienced theatre nurses but they only come for two to four weeks so have to be guided and supervised.

We also have some who come for eight or 11 weeks or longer so they can also supervise and teach, which is a help as it can be quite exhausting constantly teaching, especially when every two weeks you have a completely new group of people. Actually it’s more like teaching a new group every two to three days as all nurses want to work in ‘maxfax’ during their time on the ship.

The surgeon I work with, Dr Gary Parker, has been on the ship for 28 years! He came to see how he liked it, then met his wife and brought up his family here. He is the kindest person I have ever met. I love working with him.

I have been the maxillofacial team leader for 18 months and at the end of July will have been on the ship for two years. I started training at Middlemore Hospital 40 years ago and left in 1981 to bring up my children. I did some part-time work as a practice nurse but returned full time as a theatre nurse at Mercy Hospital in Auckland in 1996 and was a theatre nurse at Tauranga Hospital for 10 years before joining the ship.

8.00 AM Team briefing

Staff gather for the team briefing on today’s theatre list, which is part of the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist. We first introduce ourselves to each other and everyone in the room is allowed to speak and query anything they don’t understand.

It’s such a valuable tool and so many things are picked up at the briefing. Instrument and equipment requirements are discussed at this time so the surgeon and nurses know ahead of time if there will be any issues with availability.

Today we have three cases. The first patient is a 61-year-old man who had an anterior mandibulectomy three months ago to remove an ameloblastoma (a benign tumour that originates from the enamel on the teeth). He is coming today to have an iliac crest bone graft (ICBG) to cover the titanium plate that we used to reconstruct the mandible. In a certain percentage of cases involving speaking and chewing, the plate will wear through the skin either in the mouth or externally, so on Mercy Ships we endeavour to bring all our mandibulectomy patients back at three to six months and do an ICBG so this doesn’t occur.

It also gives us an opportunity to remove any remaining excess skin that hasn’t retracted. This isn’t removed at the time of the initial surgery as the skin’s memory tightens the skin up so well that the patient will actually end up with facial deformities. This surgery takes about three hours.

The second case is a 23-year-old with a parotid tumour for parotidectomy and the third case is an incisional biopsy of a maxillary tumour. This patient is also 23 and has quite a large tumour that she says first appeared 10 months ago. We are all hoping that it was longer than just 10 months because otherwise she will not have a very good prognosis. If it is not malignant, we can do a maxillectomy, but there is no point doing that if it will regrow in six months (sadly, there is no radiotherapy or chemotherapy follow-up support available).

If it is malignant, she will be referred to the palliative care team and we will pray for a miracle.

Today we have two maxillofacial medical students from Antananarivo (Madagascar’s capital city) where the country’s only maxfax surgeon works. Mercy Ships does a lot of education of health professionals so that once the ship leaves the country, the impact lives on through the ongoing education.

Also in theatre today is a Canadian nurse Mandy (new to maxfax), a Korean nurse Molly who has been in OR for two days, and Esther from Australia who has been in our OR for four weeks so is my right-hand girl. We usually have three nurses in the OR but one theatre isn’t working today so we have an extra. Esther asks to scrub up for the ICBG so that frees me to catch up on some admin. And we should all get breaks today!

12.10 PM Scrub up after quick lunch

I have to snatch a quick 10-minute lunch as thefirst case is coming to a close and I need to relieve Esther, who has been scrubbed all morning and needs to have a proper lunch break. I’ll catch up later.

1.00 PM Theatre break

We don’tusually stop at lunchtime, as it takes longer to get restarted, but the anaesthetic nurse needs to have her break as well so we have a break. During that time, I coach Mandy and Molly about scrubbing for the parotidectomy. Molly scrubs for it and Mandy is to scrub for the third case.

As Esther is to circulate, I have a chance in the afternoon to add some screws to one of the plating sets we found was short on screws yesterday and to replace a drill bit in another set. I have a long tea break during the parotidectomy to make up for my short lunch break. I also start thinking about a recent shipment of boxes of sutures that need to be stored somewhere during my admin day tomorrow.

5.15 PM Back to cabin

I often get back to our cabin before John so check my emails and bank account. I ring him about 5.30 and remind him it’s time to come home. We usually meet in the dining room. Tonight is Tuesday night so it’s ‘Africa night’, which I like but isn’t to everyone’s liking! Chicken with Sake Sake – yum! One of the girls we sit with comments that it looks like it’s already been processed. And plantain!

6.00 PM Laundry slot

We have to sign up to do our laundry. You get an hour slot to use the washing machine and then another hour to use the dryer. There’s someone following you so you have to be on time or you will miss your slot!

7.00 PM Fellowship group

On Tuesday nights I drop into Fellowship Group. There is no Bible study so I don’t get behind and if I am working late (and I often am) it doesn’t matter if I don’t make it. I am getting to meet all sorts of interesting people from all parts of the ship whom I may not normally meet hidden away in the OR. The rest of the time I am surfing the net or reading. We have a great library on the ship so it’s easy to slip up and grab a new book.

In Madagascar some lovely person has paid for us to have fast internet so we are able to watch videos and Skype our families, which is a real treat. Other evenings I go for a walk on the dock with a friend for half an hour that gets us out in the fresh air. Otherwise sometimes I get to the end of the week and realise I haven’t actually been outside.

10.00 PM Sleep time

Should be sleep time but I can’t stop thinking about storing those sutures. So John and I have a talk about them as he is the Engineering Stores manager and is very experienced in managing supplies. I then ask God for wisdom tomorrow as we are a bit overstocked at the moment and I need to do some readjusting of our stores. Then I manage to get off to sleep.

All Africa Mercy crew are volunteers, having either self-funded or, if staying longer, raised sponsorship from family, friends, colleagues, churches or community groups to cover the room and board costs of living and working on the ship. www.mercyships.org.nz

]]>The nurses were part of the first cohort of the new postgraduate programme for registered nurse first surgical assistants (RNFSAs) run by The University

of Auckland and supported by Health Workforce New Zealand (HWNZ).

Thirteen experienced theatre nurses from across the country signed up for the one-year programme that got under way in July last year as a HWNZ innovation project. Twelve of those nurses graduated this spring and while the HWNZ evaluation continues, the initial feedback is good enough for a second cohort to be already waiting in the wings to get under way in February.

Yvonne Morgan, a first surgical assistant and the programme’s clinical co-coordinator is not surprised the demand is there. Her own training as a FSA was prompted after moving into the private hospital sector in 2001 and finding herself increasingly in a de facto FSA role traditionally carried out by doctors in the public sector. “You’d never be allowed to have that role without formal training in the UK,” says the English-trained nurse who came to New Zealand in 1998 with three years of theatre work behind her. Morgan sought out and completed an Australian perioperative nurse surgeon assistant (PNSA) training programme in 2006 and since then has been a self-employed first surgical assistant working across the private and public sectors.

She was also approached by The University of Auckland, that was interested in finding out the potential demand for a FSA programme here. So in 2007-2008, as part of her master’s thesis, she surveyed the College of Surgeons and was “astounded” at the surgeons’ level of support for the advanced nursing role.

Work began on developing a programme and word of mouth had filled the first cohort last year with private sector nurses before HWNZ stepped in to support the programme as an innovation project and nurses from Auckland District Health Board also come on board.

HWNZ project manager Laura Aileone says HWNZ funding helped ensure a more transparent and robust introduction of the new advanced role, including a qualitative and quantitative evaluation of its impact.

The successful dozen

The first graduate cohort of 12 nurses was made up of nine nurses from the private sector (based in areas from Dunedin to the North Shore, including one who now works across the public and private sectors in Christchurch) and three from the Auckland District Health Board. HWNZ met the cost of all students’ fees and in addition provided some back-fill cover for the public health nurses.

This first cohort had eight to 24 years theatre experience under their belts and worked in the fields of orthopaedics, urology, cardiac, general surgery, plastics, paediatric and otorhinolaryngology (ORL or ENT).

All of the students – private and public – had to have the backing of a surgeon mentor as well as their nurse unit manager to ensure they had the support to complete the programme. The programme was made up of two papers, the equivalent of a postgraduate certificate, the first focusing on the intraoperative

role and the second on the pre and post-operative role of a FSA. Each student also kept a clinical skills logbook and they were required to meet at least the basic level for each skill to pass. They were also encouraged to carry on using the logbook until they met the advanced level.

Morgan says most of the private sector nurses on the programme had been carrying out a first assistant role to varying degrees, even if this was just holding a clamp.

It was a new role, however, for the public sector nurses who were used to working in a tertiary training hospital with registrars or junior doctors taking the first assistant role. “So first of all, they were second assistants and the registrar was operating as first assistant, then they started to share the first assistant role, and then they moved onto acting as first assistant for all or part of the procedure.”

There were 12 study days in all during the programme, including reinforcing the nurse’s anatomy and physiology knowledge with a cadaver workshop lead by three surgeons. The nurses had a hands-on learning experience of dissection through tissue during a simulation workshop using four anaesthetised live pigs, carried out under the supervision of four surgeons. The nurses found out more about the structure of the abdominal wall and how to cope with a venal or arterial bleed.

Morgan says one nurse declined to take part for religious reasons and the others were initially really squeamish. “In the end they totally forgot it was a pig. It’s got drapes on it and looks like a routine surgery scenario that we work in.” Morgan says the similarity between a pig’s anatomy and a human’s made it a “very, very effective way of teaching”.

She adds that getting clinical practice experience could prove to be difficult for the three public sector nurses, as they work in the same area of paediatric cardiac surgery.

Beyond the theatre doors

The focus of the programme was not only on what happens on the operating table but what happens before and after the theatre doors swing shut.

Morgan says many theatre nurses – including herself some time ago – know little of what’s happened pre or post-operatively with the patient under the drape sheets.

The programme fills the gap by teaching the FSAs about tests required before and after surgery, how to interpret the results and the post-operative process, including discharging a patient after surgery.

Morgan says doctors and nurse specialists on the ward have had access to this information but it hasn’t always been provided to the theatre nurse. She says one of her own patients provides a good example of what a difference knowing your patient can make. Morgan had phoned the woman prior to surgery and met her on the ward before she was due to go to theatre. “I saw she was extremely anxious and was getting herself worked up,” recalls Morgan. She also observed the patient was obese. She was able to pre-warn the theatre team that the very fearful patient would needs lots of hand holding and comforting to allay the anxiety. Morgan was also able to ensure that an operating table was used that could bear the patient’s weight and that specially adapted surgical instruments were on hand. The result of that ward visit was a much smoother event which prevented the already stressed patient from arriving into theatre to find they didn’t have an appropriate table or instruments to carry out her surgery.

Morgan says her students are also reporting the rewards of being informed, like finding out early about abnormal test results so patients don’t have to be ‘starved’ and readied for surgery, only to be informed at the last minute that their surgery has had to be delayed.

Aileone says this is backed up by initial feedback from the evaluation researchers that the programme was breeding a ‘culture of inquiry’ amongst the students. It was also providing more continuity for patients before and after their surgery.

Evaluation still under way

While the first cohort finished the year-long programme midway through 2011, the evaluation continues for a further six months. The final report is due in February 2012. Aileone says the report will present a qualitative evaluation of the new programme and role from the trainees, surgeons and other members of the surgical team, and quantitative measures of what impact the role has had on surgical through-put, reduction in surgical list cancellations and time released for surgeons and registrars to perform more complex tasks.

Aileone says HWNZ has confirmed it will support a second cohort, with 14 prospective students already expressing interest for the February intake.

Meanwhile, one of the project’s first ADHB graduates is working in a dedicated FSA role, which Morgan believes is the first such role in a DHB. The paediatric cardiac RNFSA works across the ward and theatre in a unique model that could be shared with other DHBs.

Aileone says sharing and learning across the public and private sectors is a major focus of the HWNZ-supported project so the role can be embedded in “business as usual”. “A HWNZ innovation proposal has to demonstrate it’s not just a one-off bright idea that fizzes out,” says Aileone. “It’s got to demonstrate it can embed and be sustainable in New Zealand.” ✚

Tasks of the RNFSA

The tasks of the RNFSA include traditional surgical assistant roles like skin preparation, clamping of vessels and retracting of tissue, along with extended practice roles like bone graft harvesting, suturing, tissue dissection, haemostasis and infiltration of local anaesthetic.

Background

In late 2008 the Nursing Council decided that as the first surgical assistant (FSA) role included cutting into tissue, it was outside the regular role of the registered nurse. At the time it was estimated that there were about 30 experienced nurses in the private hospital sector working in some version of the FSA role and a further 20 or so public hospital nurses trained to work in a specialist PEG tube-placement FSA role in endoscopy units.

The council’s decision was prompted by a Private Surgical Hospital Association query and lead to all FSAs being required to seek council authorisation if they wanted to continue practising in the role. Meanwhile, the council consulted on whether the RN scope of practice should be revised to allow expanded practice by suitably qualified and endorsed nurses.

About eight FSAs successfully sought authorisation before the council introduced a new enabling RN scope of practice midway through 2010. The scope allows suitably trained and qualified RNs who meet endorsed national standards to work in expanded roles like the RNFSA.

Physician assistant vs first surgical assistant

Down the road at Counties Manukau DHB, a HWNZ pilot of the physician assistant role has also just been completed.

The two American-trained physician assistants (PAs) worked to support the surgical team in a ward-based pre and post-operative role. Initial feedback has been very favourable.

Aileone says the two project teams kept each informed of their work, as neither wanted duplication or overlap. She believes the two roles are quite discreet, as the PA didn’t take an intraoperative role.

However, Morgan believes there potentially is some overlap, as the RNFSA model developed at ADHB involves a similar pre and post-operative role to the role that PAs had been filling in Counties Manukau.

She points out that in the US the PA role is very similar to the RNFSA role and there is also overlap with the American NP role. It has been argued that while the US has the population to support all three roles, New Zealand doesn’t. So communication over any overlap has been important. “One of the worries is that if there was too much similarity between them the role wouldn’t become viable.”

Morgan says the FSA qualification is on the master’s degree pathway and some could carry on to seek nurse practitioner status. She has a master’s degree herself but says unfortunately her role includes all the NP-required elements bar prescribing. But she says that doesn’t mean that other FSAs practice in the future couldn’t include prescribing, making them eligible to seek NP status.

]]>