“Industry should know we are pretty serious about making sure this is dealt with,” Ardern told Mike Hosking on Newstalk ZB.

Her comments come after the Herald reported new Health Minister David Clark as not ruling out regulation or a tax. Ardern reiterated that position.

“We know we have got a problem. And I think people would be surprised by how much sugar is being placed in everyday items.”

Ardern said a sugary drinks tax was not the only answer, given the high sugar content across other processed foods.

“We want to work with industry to try and get that rate of use down. Try and encourage industry to do that themselves. But we are leaving all options on the table.

“We are making sure we use some of the options that still exist before that [considering a sugary drinks tax]. There are examples in the UK where they got salt down dramatically by working alongside industry. We should make use of those options.”

Professor of Population Nutrition and Global Health at the University of Auckland Boyd Swinburn said Labour was right not to rule out tough action including a sugary drinks tax.

“It is actually very refreshing to see a government who is prepared to look at the evidence and look at every possibility that’s on the table that’s been recommend. So this is a breath of fresh air,” Swinburn told Newstalk ZB.

Labour accused the last Government of inaction on the issue of obesity and accused some manufacturers of rigging a labelling system designed to flag healthy products to shoppers.

Health Minister David Clark said his preference was to work with the industry to develop a better front-of-pack labelling system, and to set firm goals to reduce sugar content in packaged food.

Clark said there was “growing evidence” around the effectiveness of a sugary drink tax, but such a step wasn’t a silver bullet because it was only focused on drinks.

“I want to talk with industry first before going down any track like that.”

One likely change will be to labelling on food packaging. Currently there is a Health Star Rating System that is meant to signal the healthiness of the product by the number of stars on the front of the packet.

Clark believes there is a flaw in the voluntary system, in which manufacturers can “cancel out” the effect added sugar and other unhealthy ingredients have on a star rating if the product contains healthier ingredients like grains.

He said he would seek further advice on whether the Health Star system would be retained, or a new front-of-pack system introduced.

“There are some anomalies in the current system. It seems strange that breakfast cereals can have some fibre in them and then suddenly they get a high star rating despite having a lot of sugar.”

Asked if front of package health labelling could be made mandatory, Clark said he would consider all options but wanted to get advice first, and talk to industry.

Labour’s previous health spokeswoman, Annette King, said she agreed with celebrity chef and healthy food campaigner Jamie Oliver that people would be more conscious of what they were eating if they knew the number of teaspoons of sugar or salt that is in their food, and Clark has said a label that displayed such information could be helpful.

“I think there is room for more explicit labelling to indicate the amount of sugar in food products,” Clark told the Herald.

“And I also want to have constructive conversation with industry about how they think they could reduce sugar content over time in products. Personally, I think the most constructive approach is to work with industry. But I have also indicated that if the result that we need isn’t achieved then we are prepared to regulate.”

Timelines would eventually be set, Clark said, but he acknowledged that wouldn’t be straightforward.

“My experience is industry prefers to have clear expectations and be able to manage its own destiny. So I’m hoping that there will be a constructive relationship there.”

The New Zealand Food and Grocery Council declined to comment.

Sue Chetwin, chief executive of Consumer New Zealand, said the current Health Star system had serious flaws and her organisation supported an overhaul, and wanted it to be mandatory across more products including frozen foods.

“What they really need to do is change the algorithm … a cap would be a simple way so once you got to a certain level of those bad foods then you couldn’t get a Health Star rating that was, say, above two or something like that.”

Another change supported by Consumer that will likely be made under the new Government is a requirement for country of origin labelling on single ingredient food such as fruit and meat.

Former Green MP Steffan Browning’s Consumers’ Right to Know (Country of Origin of Food) Bill is at select committee stage, having been supported at first reading by all parties except Act.

]]>Tokoroa’s Ka Pai Kai was one response to growing concern over ‘food swamps’ – the over-abundance of unhealthy but ready-to-eat foods in communities, Zaynel Sushil of Waikato District Health Board’s Population Health Unit told the Christchurch conference.

He said very recent research conducted in New Zealand confirmed deprived areas had approximately five times more fastfood outlets and convenience stores than grocery outlets. Exposure to cheap and easy unhealthy food was about three times higher for schools in deprived areas.

“The food environment where we live, work, learn or play influences our food choices. Food swamps and social problems like poverty all follow a similar pattern and some suggest this can lead to a vicious cycle where people are less able to act in their own long-term interests,” he said.

Ka Pai Kai set up a local food network to help the Waikato community work together to build a sustainable local food system. The Ka Pai Kai action plan included food provision, at-risk youth training, café food and waste policy, councils and indigenous food networks.

“It began with a healthy school lunch programme, transformed into a community social enterprise and, since its inception in March 2015, three kohanga, a preschool and nine primary schools have joined.”

This year the Network was recognised by the philanthropy sector as a project for intergenerational change and awarded a significant funding boost, said Sushil.

Healthy school lunches

In another presentation West Coast Community and Public Health Nutrition Health Promoter Jade Winter told the conference about workshops on the West Coast where they provided examples of nutritious and cost-effective lunchboxes.

These included foods such as pasta, carrot sticks, bananas, plain yoghurt, kiwifruit, filled bread cases, boiled eggs, celery sticks, rice crackers, broccoli, hummus and homemade slices.

The cost, at an average of $2.31 per meal, was based on supermarket prices on the West Coast.

“I always explain to parents that providing a healthy lunchbox at a low cost will nearly always require a little time. However, by chopping up extra vegetables at dinner time, or making extra, you are potentially saving time and power!”

Ms Winter said it soon became obvious that parents and caregivers needed a robust, budget-friendly, easy to understand resource so Community and Public Health produced Nourishing Futures with Better Kai. The booklet combines nutrition information and guidelines with practical information such as handy ingredients for the pantry, building a healthy lunchbox, sandwich-filling ideas, healthy party food, dealing with picky eating, oral health and recipes for using leftovers.

Ms Winter said the booklet has had significant input from parents, caregivers, teachers, dietitians, nutritionists and public health professionals to ensure it is as useful as possible.

“Toddlers and young children need appropriate nutrition for growth and development. Eating habits are formed from a very young age and it is important to cultivate these as early as possible. Introducing nourishing foods encourages children to learn about and enjoy different tastes and textures. We hope the resource will help parents and caregivers with that.”

Nourishing Futures with Better Kai is available free on the Community and Public Health website at www.cph.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/nourishingfuturesbetterkai.pdf.

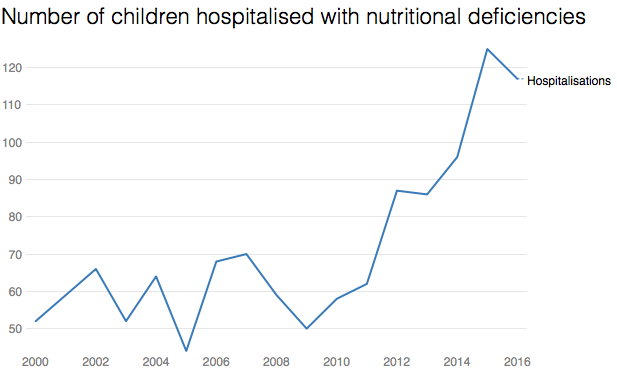

]]>Child hospitalisation data shows around 120 children a year now have overnight stays due to nutritional deficiencies and anaemia, compared to an average 60 a decade ago.

Doctors say poor nutrition is also a factor in a significant proportion of the rest of the 40,000 annual child hospitalisations linked to poverty – and that vitamin deficiencies are more common in New Zealand compared to similar countries.

“Housing, stress and nutrition – it’s all tied together,” said pediatrician Dr Nikki Turner, from the Child Poverty Action Group. “If you want to eat nutritiously on a low-income it’s difficult, and that means you’re more likely to get sick and stay sick for longer.”

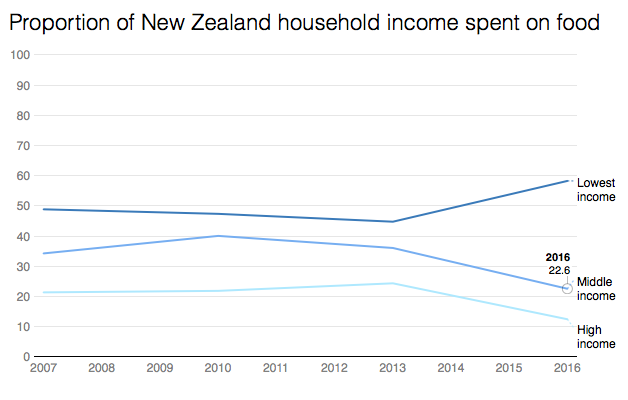

The new health data comes as food prices continue to rise, with the consumer price index last week indicating food costs were up 2.3 per cent on a year ago. At the same time, income in the poorest third of households has remained flat since 1982.

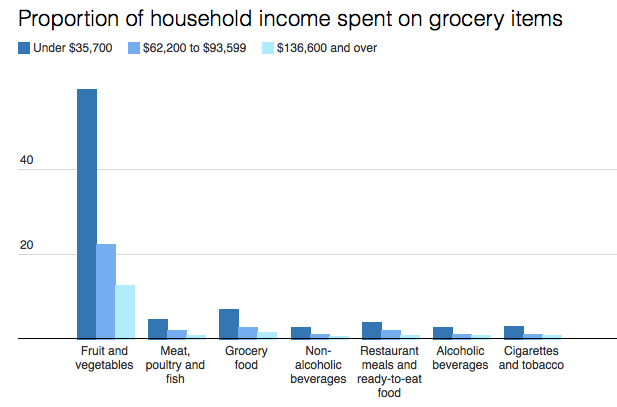

Statistics New Zealand information released to the Herald shows for families on the lowest incomes (under $35,000), that means they’re now spending 60 per cent of their income on food, compared to 48 per cent in 2007.

More than half of that goes on fruit and vegetables, data shows. Among middle-income families, 22 per cent of income goes on food, with one fifth of that on fruit and vegetables.

An Australian paper has suggested that “food stress” is believed to be experienced when more than 30 per cent of income is spent on groceries.

In practice, “food stress” means increasing reliance on food banks, charities, cheap “fillers” like white bread and noodles, or simply going without.

“I try to fill up the pantry but it only lasts one or two days and then it’s empty again,” said solo dad of three kids, Daniel*, from Otara. “I have to skip my own lunches because the kids are always hungry and I try to prioritise school lunches for them. I know that’s important.”

Dr Cameron Grant, the head of paediatrics at Auckland University, said it was rare for children to be hospitalised for severe nutritional issues in New Zealand, malnutrition was a factor in a significant proportion of illnesses.

“A third of children hospitalised at Starship have iron deficiency, for example,” Grant said. “A lack of vitamin D is also very common. That increases the risk of respiratory illnesses.”

New Zealand rates of iron deficiency are twice as high as Europe, the UK and Australia, he said, and Vitamin D deficiency was higher than the USA, because our food lacked nutrients.

However, New Zealand diets were also energy rich, meaning children could be both undernourished and obese – a situation that was not improving.

Child Poverty Action Group’s Turner said contrary to popular opinion, it wasn’t an issue of poor budgeting causing the problem.

According to household income data, low-income families spent about the same on cigarettes and alcohol as middle-income earners, for example.

“Low income families are not wasting money any more than anyone else, but it just doesn’t stretch far enough,” she said.

The University of Otago 2016 Food Survey estimates the basic weekly food cost for a man is $64 per week. For a woman it’s $55, and a 5-year-old is $40.

Research at the Auckland City Mission found families coming for food parcels have an average $24 per person each week for all groceries. That’s around $3.50 a day.

However, Massey University PhD candidate Rebekah Graham, who researches food insecurity, said some people had even less – such as one woman who had only $25 a week for herself and two children.

The food she bought – tinned fruit, bacon-and-egg pies, noodles – was barely enough to meet the family’s food requirements. Despite that, the woman still bought a cake as a gift for friend suffering a bereavement.

Graham’s research found families frequently had to make terrible choices to survive. One woman, surviving on $1 loaves of white bread, was unable to produce enough milk to feed her baby. Others put off urgent dental work. She also heard of people taking sleeping pills on a Friday so they could sleep through the weekend and not have to pay for food.

Chief executive of Variety, the Children’s Charity, Lorraine Taylor said food was always the first thing to go if families needed something – whether that was school uniforms or doctor’s bills. They also heard of parents not eating to feed their kids.

The charity, which runs a child sponsorship programme but is increasingly propping up families with food vouchers, said it was unacceptable that charities were left to fill the gap.

“Food should not be a negotiable. We want to live in a country where all Kiwi children are fed nutritious food.”

The Ministry of Health’s principal nutrition advisor Elizabeth Aitken said it last carried out a national children’s nutrition survey in 2002, and did not have more recent data on quantified nutrient intakes for children.

It said diet was just one of a range of causes of anaemia and nutritional deficiencies, but it knew obesity was increasing from poor quality diets.

The ministry had a range of programmes to help parents with advice on nutrition and development, she said.

Daniel’s family

The kids are always hungry at Daniel’s house, but the cupboards are almost never full.

A solo dad to three school-aged kids, he struggles to make the groceries last the week, even though he skips his own lunches and uses all the leftovers – and attended a budgeting course to learn how to make money go further.

“Sometimes I have to lock the cupboard to make sure we have enough,” he says. “I find it hard.”

Daniel – which is not his real name – has at most $200 to spend a week on food, depending on bills or how much work he gets. He earns about $500 a week. His rent it $180, for a three-bedroom in Otara.

The only fruit he buys are apples and oranges, even though his kids love grapes, and they eat toast and spaghetti for dinner most nights a week. A cooked chicken is a luxury, only for special occasions. The kids never buy their lunches, instead having bread and cheese, maybe a muesli bar, and a piece of fruit.

“I know it doesn’t look good if they don’t have lunch,” Daniel says. “I have to skip my own lunches because the kids are always hungry and I try to prioritise school lunches for them. I know that’s important.”

A sponsorship – through the charity Variety – has helped, helping with the children’s shoes and clothes, and occasional supermarket vouchers.

Sometimes, however, the bills push him to line up at the food bank for a parcel, even thought he hates it.

“I feel embarrassed at times, but I just had to tell myself that we are desperate,” he says. “I have no choice.”

]]>

A University of Otago study, published in the international journal JAMA Pediatrics, looked at whether allowing infants to control their food intake by feeding themselves solid foods instead of traditional spoon-feeding, would reduce the risk of becoming overweight up to age 2.

The study, led by Professor Rachael Taylor and Associate Professor Anne-Louise Heath, found no difference in body weight or energy intake between spoon feeding and baby-led weaning (BLW) but did find other benefits.

Taylor said it did provide evidence that babies who fed themselves from the start had a better attitude towards food and were less fussy about food than the spoon-fed children in the study.

]]>

This New Zealand-developed app allows the user to search and compare nutritional information, ingredients and claims on 8,000 New Zealand food products.

Using their smartphone or tablet the user can scan the barcode of a food label and get easy to interpret nutritional information on the product using a traffic light-style colour rating for levels of total fat, saturated fat, sugar, and salt. This allows them to compare products at a glance. They also receive immediate suggestions for ‘healthier’ alternative foods or products.

PROS include: Produced by trustworthy organisations: The University of Auckland’s National Institute for Health Innovation, The George Institute for Global Health, and Bupa New Zealand.

CONS include: Does not include information and messages on portion size.

More information on this and other reviewed apps at:

www.healthnavigator.org.nz/app-library.

Full FoodSwitch review at: https://www.healthnavigator.org.nz/app-library/f/foodswitch-new-zealand-app/

The NZ App Project: Health Navigator, a health website run by a non-profit trust, is using technical and clinical reviewers to develop a New Zealand-based library of useful and relevant health apps. Nurses are invited to support the project by either recommending consumer-targeted health apps for review and/or offering to be app reviewers. Email [email protected] to find out more.

Julia Rucklidge is no believer in there being one magic ingredient or wonder food. “I just don’t think it’s out there,” says the professor of clinical psychology at the University of Canterbury.

But the researcher is increasingly convinced that there are strong links between nutrition and mental illness. For the past decade she has been running randomised controlled trials (RCT) to investigate the impacts of a cocktail of micronutrients on mental health issues, from ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) to the anxiety, stress and trauma associated with the Canterbury earthquakes.

Her findings, which have been published in the British Journal of Psychiatry, saw her receive the New Zealand Psychological Society’s Ballin Award in 2015 for contributions to psychology and a 2014 TEDx talk on her work has been viewed more than 350,000 times – and that number is still growing.

Rucklidge was initially very sceptical that nutrients could be effective in helping to treat mental illness. “I thought if it was that simple we would have figured this out already.”

But prompted by initial positive findings by her PhD supervisor back in her native Canada – and frustration at poor outcomes from conventional treatments for ADHD – she began her own research in the field upon arriving in New Zealand (see box).

“I’ve now been running clinical trials over the last 10 years and all our data are very robust in finding that, over and over again, giving broad-spectrum micronutrients – 36 vitamins and minerals in combination with no one magic ingredient – can help many people (experiencing mental illness). Certainly not everyone is cured by nutrients, but we can help a lot.”

No single answer

Rucklidge is quick to point out that she does not see nutrition as a standalone treatment for mental illness. Neither does she believe that bad diets, or nutritional deficiencies, are the root causes of mental illness, but are instead just one more contributing factor.

Her research trials focus on the impact of that one variable – taking micronutrients – but in the ‘real world’ she advocates a multi-layered, evidence-based approach to preventing and treating mental illness, including lifestyle factors such as exercise and eating healthily (adding supplements when required), and using stress reduction techniques such as mindfulness and psychological therapies such as cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT).

She is also not advocating that people who are currently on medications should stop taking them and swap to micronutrients (any change of medication should always be discussed with the patient’s prescriber and, if undertaken, done slowly and under close professional monitoring).

But she would like to see a shift to people being prescribed, or seeking out, medications such as antidepressants only when other approaches have been deemed unsuccessful, and says, “I think we need to stop seeing them [medications] as frontline treatment.”

She, for one, believes that many medications are over-subscribed, with one in eight New Zealand adults currently taking antidepressants and about a quarter of a million Kiwis being on prescription sleeping pills.

“We know that the data is very clear that medications (like antidepressants) are very effective in the short-term,” she says.

But people are often on medications long-term and it is the long-term efficacy data published within the past decade that Ruckledge believes people should be concerned about, as this indicates, for example, that in the long-term antidepressants are having little impact on depression recovery and relapse rates.

Why micronutrients?

So if taking a cocktail of micronutrients is having an effect on some people’s mental illnesses, it begs the question: why does it work?

“That is the million-dollar question,” says Rucklidge. “We are trying to figure that one out – we have lots of ideas and hypotheses about why [micronutrients] might work.”

One hypothesis is that people aren’t eating diets as rich in nutrition as they once did. Epidemiology studies have indicated that the more that people eat a modern western diet – high in processed foods, refined grains and sugary drinks and low in vegetables and fruits – the more likely it is that mental health issues will emerge.

Rucklidge points out there are a host of other factors contributing to the rise in mental health issues – including poverty, genetic predisposition, the stress of modern life and domestic violence – but eating a sensible, whole-food diet that is high in fruit and vegetables may contribute to curbing the trend.

She adds that even people who do eat well may not be getting the nourishment they did a century ago because of factors such as mineral depletion in the soil resulting in less nutrient-dense plants, and an emphasis on appearance and shelf-life over the nutrient values of food.

So some people, she argues, because of their genetic programming, may be more vulnerable to developing mental illnesses because they are getting insufficient nutrients for their metabolisms – even if they are eating what are considered ‘good’ diets. Supplementing those people’s diets with micronutrients may potentially correct that nutrient imbalance.

Rucklidge points to the work of Bruce Ames, a biochemist and emeritus professor at the University of California, Berkeley, whose research has included looking at the role that the 30 essential vitamins and minerals play in the formation of proteins and enzymes.

Ames’s findings include that high doses of some vitamins could successfully treat more than 50 genetic diseases, particularly inherited metabolic diseases caused by defective enzymes, and he believes that eliminating vitamin and mineral deficiencies in the general population may restore what he calls “metabolic harmony”.

Rucklidge says this makes her team wonder whether Ames’s work also applies to mental illness, because vitamins and minerals are required for the enzymes needed to make neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine and adrenalin.

“So are we [with the broad-spectrum supplement] providing the nutrients necessary for these neurotransmitters? Very potentially, yes.”

Likewise, they hypothesise, they could be helping to feed the mitochondria that are the energy factories of human cells and possibly helping to overcome some people’s issues with the gut absorption of nutrients.

The micronutrient formulas that Rucklidge uses for the trials (she points out that neither she nor the university sells or makes money from the brands they use) take a ‘shotgun’ approach by delivering 14 vitamins, 16 minerals, three amino acids and three antioxidants in much higher doses than you would find on your supermarket shelves. The research team doesn’t know which of the array of shotgun pellets, i.e. ingredients, are making a difference – or what dosage – and she says it may be that different ingredients are important for different people.

In the future, researchers may be able to personalise micronutrient formulas to meet an individual’s needs based on their genetic profile and nutrient levels. “But we are not there yet so we take the shotgun approach that our bodies have evolved to know what to do with nutrients – so those you don’t need you will pee out.”

She says that to date they have observed no side effects from their research participants and are currently monitoring and collecting data on long-term users. Taking high-dose micronutrients poses potential risks for some people – for example, those people with genetic disorders causing copper metabolising difficulties or haemochromatosis (iron overload).

Eating ourselves better

Can we just eat our way to better mental health?

Rucklidge says she can’t recommend the perfect diet for better mental health – the clinical psychologist says it isn’t her area of expertise. Research into different dietary regimes also indicates that a person’s genotype may influence why some lose weight under diet ‘x’ and others don’t – similar effects are likely to apply to any mental health benefits.

“But what I can say very confidently is the more you eat crap food, the worse you are going to feel. And there isn’t a single study out there that shows the modern western diet has been of great assistance to us.”

So the simple message she would share is for people to reduce the amount of processed food they eat.

“That is a general comment I can feel confident about, as I haven’t seen any studies that show eating highly processed, packaged foods is having a wonderful outcome for people.”

She also endorses food activist Michael Pollen’s simple guide Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.

But Rucklidge’s research, and that of others interested in the field, indicates that what people are eating right now might not adequately meet the nutritional needs of those with mental health issues. Some people may be able to meet those nutritional deficiencies by dietary change, but Rucklidge believes, after observing hundreds of people in her studies, that other people may need to take additional nutrients, probably because of their particular genotype.

“I’ve seen some people on some unbelievably excellent diets – diets that I could not fault – who have made all the lifestyle changes, yet they are still depressed or anxious. But they have had favourable responses to taking broad-spectrum micronutrients.”

Food for thought indeed.

ADHD study

Rucklidge’s largest published study to date, in the British Journal of Psychiatry in 2014, was a blinded, randomised, controlled trial looking at the impact of a nutrient supplements on 80 adults with ADHD who were not currently taking any psychiatric medications.

For eight weeks 42 of the participants took a broad-spectrum micronutrient formula (15 capsules a day of 14 vitamins, 16 minerals, three amino acids and three antioxidants) and the other 38 took 15 placebo capsules (containing a small amount of riboflavin to mimic the smell and urine colour associated with taking vitamins).

The study found significant differences in self and observer ADHD rating scales between those who were taking the active supplements and those who were not. Clinicians did not observe differences between the groups on ADHD rating scales but did rate those taking the micronutrients as being more improved in their global psychological functioning and their ADHD symptoms. Further analysis also found a greater improvement in mood for the participants with moderate to severe depression who were taking the active capsules.

Quake stress study

Another study compared the impacts of two micronutrient formulas on Christchurch adults who were experiencing heightened anxiety or stress two to three months after the February 2011 earthquake.

The 91 adults were randomly assigned to take either an over-the-counter micronutrient formula, a lower dose of a specialist micronutrient formula, or a higher dose of the specialist micronutrient formula. All three treatment groups were monitored during the one-month trial and for one month afterwards.

All participants experienced significant declines in psychological symptoms but those taking specialist micronutrients experienced a greater reduction in intrusive thoughts, with the high-dose specialist micronutrient group reporting greater improvements in mood, anxiety and energy.

A year after completing the study, 64 of the original participants (plus 21 of the 29 non-randomised controls) were re-assessed. The study found that all groups had experienced significant psychological improvements, but treated participants had better long-term outcomes and those who had stayed on micronutrients (or stopped all treatment) reported better functioning than those who had switched to other treatments, including medication.

MORE INFORMATION:

International Society for Nutritional Psychiatry Research

Lists research published in the area of nutritional approaches to the prevention and treatment of mental disorders www.isnpr.org

Mental Health and Nutrition Research Group, University of Canterbury

Information and contact details for Julia Rucklidge’s research projects

www.psyc.canterbury.ac.nz/research/Mental_Health_and_Nutrition/index.shtml

TEDx Talk

What if nutrition could treat mental illness? by Julia Rucklidge (2014)

www.youtube.com/watch?v=3dqXHHCc5lA

In people with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease, regular omega-3 supplements do not appear harmful but have no beneficial effect as a treatment for dementia when compared with a placebo. More research is required to determine the effect of omega-3 supplementation in people with other types and severity of dementia, including those who are nutritionally deplete.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

You work in long-term residential care and note that several residents with dementia are taking regular omega-3 supplements in the belief that this improves brain function and slows the progression of dementia symptoms. Foods rich in omega-3 fats such as oily fish are important for a healthy balanced diet but you are unsure of the safety and benefits of omega-3 supplementation for treating dementia. You decide to review the evidence.

QUESTION

Is omega-3 supplementation – over and above usual diet – a safe and effective option for treating cognitive and functional decline in people with dementia?

SEARCH STRATEGY

PubMed- Clinical queries (Therapy/Narrow): omega-3 AND dementia

CITATION

Burckhardt M, Herke M, Wustmann T, Watzke S, Langer G, Fink A (2016). Omega-3 fatty acids for the treatment of dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4:Cd009002.

STUDY SUMMARY

A Cochrane systematic review assessing the efficacy and safety of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) supplementation for the treatment of people with dementia. Inclusion criteria were:

Type of study: Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing omega-3 PUFA (either as a supplement or an enriched diet) with placebo. Studies were to include people with dementia diagnosed using accepted diagnostic criteria. Dementia could be at any stage or severity. Studies investigating only dietary advice, or not specifying the intake of omega-3 PUFA, were excluded.

Types of intervention:

- Dietary supplements of any dose of omega-3 PUFA capsules versus placebo. Omega-3 PUFA was to be the main active ingredient of supplementation and given regularly (at least weekly) for at least 26 weeks.

- Diets enriched with omega-3 PUFAs in specific portions versus usual diet.

OUTCOMES

Primary outcomes: changes in global and specific cognitive function, functional outcomes {e.g. activities of daily living (ADL)}, overall dementia severity and adverse effects.

Secondary outcomes: quality of life (QoL), compliance with the intervention, symptoms associated with dementia (e.g. mood changes), entry to institutional care, hospital admissions, and mortality.

STUDY VALIDITY:

Search strategy: Reviewers searched ALOIS, the specialised register of the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group up to December 2015 to locate eligible studies. This register holds dementia research identified from major healthcare databases {MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), CINAHL, PsycINFO and Lilacs}, international trial registers, and sources of grey literature. In addition, major healthcare databases were searched separately, manufacturers of omega-3 products contacted, and conference abstracts and reference lists of included studies reviewed. No language restrictions applied.

Review process: Two reviewers independently examined titles/abstracts and then full text to identify relevant studies. Two reviewers also independently extracted data, performed or checked data entry, and assessed study quality. Discussion or involvement of a third person resolved differences in opinion.

Quality assessment: The Cochrane Collaboration tool was used to assess risk of bias in included trials. The tool looks at random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and potential bias from industry involvement.

Overall validity: A high-quality review involving high-quality studies.

STUDY RESULTS:

After the removal of duplicates, 2332 articles were screened, of which 31 full-text articles were considered for inclusion. Three RCTs involving 632 participants were included in this review. All participants had Alzheimer’s disease (AD) of mild to moderate severity. Trials involved similar doses of omega-3 PUFA supplements (between 1.75 and 2.3 g/day). Trial duration varied and was for either six, 12 or 18 months. At six months, there was no significant difference between those taking omega-3 PUFAs and those receiving placebo for changes in cognitive function, changes in functional outcome measures (activities of daily living – ADL) or overall dementia severity (see table). There were also no significant differences between groups for QoL and mental health symptoms. Non-significant results were observed regardless of the dose and duration of supplement intake. Tolerability was poorly reported in the included studies, although serious adverse events appeared to be uncommon.

COMMENTS:

- Participants were similar at baseline for relevant characteristics including use of AD medication, dietary intake of omega-3 and MMSE score. Increased serum fatty acid levels in the omega-3 supplement but not the placebo groups indicated good compliance with the intervention.

- Study quality was high and all outcomes were measured using validated tools. Non-significant improvement in cognition with omega-3 supplements was considered too small to be clinically significant.

- A significant improvement in instrumental ADL (ability to live independently) observed in one very small pilot study requires confirmation with further research.

Reviewer: Cynthia Wensley RN, MHSc. Honorary Professional Teaching Fellow, the University of Auckland and PhD Candidate, Deakin University, Melbourne [email protected]

]]>