But the daily dressing of her terminal malignant wound was just too painful without the relief of Entonox gas, traditionally only available in secondary care.

As Julie lay in Christchurch Hospital wishing to be at home – and to be as normal as possible for as long as possible – a team of Nurse Maude nurses rallied to make her goal achievable.

The team presented to the recent Clinical Nurse Specialist Society conference on how meeting Julie’s wish motivated them to – within a week – fast-track the policies, training and equipment that were required to enable Nurse Maude district nurses for the first time to deliver home-based Entonox (a mix of nitrous oxide and oxygen) pain relief.

The results were that not only did Julie get to return home to be with her husband Ken*, but also the innovation she motivated has seen home-based Entonox used again for another wound care patient facing severe acute pain when her wounds were cleaned and dressed.

Unlike other forms of pre-and post-dressing pain relief, Entonox works quickly, gives the wound care patients control over their own pain and is short-acting, so doesn’t leave them drowsy for the remainder of the day.

Julie’s story

Julie was a 63-year-old woman with a strong belief system, a very supportive husband and a close circle of family and church friends, says palliative care nurse specialist Mary Fairhall.

She was first diagnosed and treated for metastatic rectal adenocarcinoma in 2013 but the cancer returned in 2015 and treatment was unfortunately unsuccessful. When Fairhall met Julie in late 2016 the palliative patient had an extensive fungating tumour on her back producing a lot of exudate, and the daily dressings of the large, open, tunnelling wound were causing severe pain and nausea. The team tried to address the pain by using oxycodone before and after dressings but Julie still rated her pain five-out-of-five at dressing change time.

This led to Julie being hospitalised, where she was reviewed for analgesia and cares. The “transformative” change was using Entonox gas for dressing changes, as it dramatically reduced Julie’s pain during wound dressings from a five-out-of-five to a one-out-of-five, or even a zero.

But Julie had a real desire to be at home and to live a life as normal as possible. The barrier was that Nurse Maude – or any other district or palliative care nursing service that they knew of – had never delivered Entonox at home.

The high oxygen content of the 50/50 nitrous oxide/oxygen gas means transporting and storing the Entonox gas cylinders is not without risk. District nurses were also not trained in delivering Entonox, and would be doing so in a person’s home without the back-up support available to hospital nurses if there was respiratory failure – so training and processes were required to be in place to keep both nurse and patient safe.

Speedy response

Nurse Maude decided to see meeting Julie’s goal of being home “as an opportunity rather than a challenge”, says Rose McConchie, Nurse Maude’s community clinical nurse educator.

“Our main constraint was time,” says McConchie. Julie started to deteriorate in hospital and the team knew they needed to do a lot in a hurry. This included training, creating safety policies and protocols; and working out how to supply and fund Entonox in the home.

“Certainly the pressure was on,” says McConchie. But, she says, they had a great collaborative team in the oncology ward team, the palliative care team, the wider Nurse Maude team (including the Community Nursing Service Manager and the Clinical Nurse Manager), the gas provider BOC, and Julie’s family.

McConchie had to create Entonox usage guidelines for the patient, a gas monitoring and re-ordering system, and a consent form for storing Entonox gas in a private home. The consent form set out a safety checklist, which included that the storage space should be well ventilated and there should be no open fires, no smoking, and no mobile phone use near the cylinder and its combustible contents.

The district nursing team in Julie’s area needed to be trained to be competent to deliver Entonox for Julie and to respond in a respiratory emergency. The aim was to assign two nurses for each wound dressing – one to do the wound care and the other to deliver the Entonox. The nurse administering the gas has a pulse oximeter to check the patient’s oxygen saturation, and monitors their pulse, blood pressure and sedation level to ensure the patient is not over-sedated. Oxygen, a mask, and emergency equipment are also on hand in case there is respiratory failure and an airway needs to be inserted.

The Entonox training was done speedily by McConchie completing the DHB’s online Entonox training package and being signed off by Canterbury DHB nurse educators as competent, before going on to sign off the district nurses one by one as they each completed the online competency training.

Innovation brings ease

The result was that within one week Julie was able to return home. The thankful patient told the team that their efforts meant she was “much more at ease, much more relaxed and her pain was much better”.

In addition, “her family and friends could visit any time and the pressure was taken off her supportive husband”.

District nurse Elizabeth Croton says she had cared for Julie and Ken in their home so was quick to say yes to Entonox training.

“I knew them both well enough to know that they would both want to be home for these final weeks,” said Croton. “The Entonox training was going to enable this to happen and give me the confidence and skills to provide that care at Julie’s home.”

Julie’s goals wanted to live as normal a life as possible with family and friends in a home that was ‘non-medical’, apart from a treatment room where the dressing changings were carried out. “Her husband was thrilled to have her at home,” said Croton.

Fairhall said the team continued to adhere to Julie’s wishes. In mid-July Julie and her husband requested a hospice admission and she died peacefully five days later.

The Nurse Maude team was very proud that with the support of many they were able to rapidly respond to Julie’s wishes. The creative ‘under the pump’ response has also resulted in a robust process for prescribing and delivering Entonox in-home on future occasions.

Nurse Maude District Nursing has already had another referral, by a nurse practitioner, for delivering Entonox to a woman who had surgery on abscesses under each arm that required cleaning by irrigation and then packing of the healing wound – a process the woman found very painful.

McConchie said the short-acting nature of Entonox made it perfect for painful procedures such as this as it was quickly out of the system, unlike traditional pain relief like morphine. Using Entonox meant this client could get up straightaway, have breakfast, get on her bike and carry on doing what she needed to do for the rest of the day.

The legacy of Julie’s wish is expected to be more wound care clients whose pain needs are not being well met by traditional means being considered for home Entonox treatment. More patients will also be able to choose to receive care in their own homes – reducing both costs to the taxpayer and stress to palliative patients who, like Julie, just want to go home to their own beds.

*Julie and Ken are pseudonyms

]]>Our very own NZNO College for Infection Prevention and Control Nurses is affiliated with this UK-based international organisation. The IFIC’s stated mission is to facilitate international networking in order to improve the prevention and control of healthcare-associated infections worldwide. This site provides free full-text access to the International Journal of Infection Control. Additionally, there is full access to the 2016 edition of IFIC Basic Concepts of Infection Control, which provides a resource of research-based concepts to support the development of local policies and procedures in a number of languages. [Site accessed 2 October 2017 and date of last update is unknown].

Child Health Research Review

www.researchreview.co.nz/nz/Clinical-Area/Paediatrics/Child-Health.aspx

This New Zealand site provides digests of international research across a number of fields. With over 10,000 medical journals from over 50 areas reviewed, this site makes it easy to keep up to date with podcasts and research article reviews. All you need to do is register and select your area of interest for free email updates. This specific review page features key medical articles from global paediatric journals with commentary from a rotating team of Starship paediatric specialists. The Child Health Research Review covers topics such as paediatric endocrinology, nephrology, pharmacology, fractures, immunology, adolescent health, and paediatric neuropsychology. Research Review publications are free to receive for all NZ health professionals. [Site accessed 2 October 2017 and last updated 2017].

]]>

In this article I share some advice I think could be useful for you beforen start your clinical placement.

Some advice for your first clinical placement

-

Be prepared and have a solid support system in place

You are likely to encounter situations and cases you have never been exposed to before. Take a moment to process these experiences and, if needed, vent to your family and friends (while protecting patient confidentiality, of course).

-

Introduce yourself to the healthcare team and be a positive team member

Introducing yourself helps start a friendly and open relationship with your colleagues. Being a positive team member makes you stand out as someone who wants to be there. And you won’t be labeled as just ‘the student’.

-

Mistakes happen

We are only human! Try not to dwell on your mistakes. Instead focus on what you could have done better and how you can learn from the situation. Don’t be afraid to talk through your mistakes with your preceptor; they are there to support and guide you on how to learn from your mistakes.

-

Be prepared for your first patient death

Watching families and friends in emotional pain while their loved one dies is a hard pill to swallow. You may be present for the deaths of babies, children, adults and older people. I found the best way to support someone who is grieving is by providing privacy and comfort. This may involve being ‘all ears’ or simply providing cups of tea. It all makes a difference.

-

Be ready for the long hours

If you’re anything like me you may not be used to working 8-12 hour shifts for three to four days a week. Standing and walking for eight-plus hours, holding your bladder, moving and handling patients weighing more than 120kgs; these are just a few of the physical battles you may deal with each day. So it is important to take care of yourself too. Many nurses develop back problems from lifting patients, so learn to use proper techniques and don’t be afraid to ask for a helping hand. A good pair of comfortable shoes is also essential!

-

Don’t be afraid to put your hand up and ask to do new things

We’re there to learn, right? So don’t shy away or expect the nurse to always come to you. Be assertive and step out of your shell. The best learning happens with practice, so give it a try while you have supervision.

-

Volunteer to make beds and hand out meals

I know these aren’t the best jobs and you’re probably thinking I didn’t come to nursing school to make a bed, however you are part of a team. Helping out your team members and doing little jobs really makes the difference. It shows people you are a helping set of hands and are willing to do pretty much anything.

-

Learn what to do if there is an emergency

It’s easy to feel like you’re in the way of nurses and doctors when there’s an emergency. Ask your preceptor what your role should be if an emergency occurs. This may just be clearing and decluttering the surroundings or being a runner. But be ready to put yourself out there and ask if you can do the vital signs or assist in other ways.

-

Have a notebook in your pocket to jot down key words

I’ve found it helpful to have a notebook in my pocket to jot down medications, illnesses, procedures, and anything I need to learn at a later date. It’s hard to remember things when you have a busy schedule, so this helps get around that.

-

Workplace bullying can happen

Students can sometimes be seen as a burden for nurses who don’t want a long, dragged-out shift. My advice is to tell your preceptor upfront what you can currently do within your scope of practice, and what you would like to achieve from the shift. This will hopefully sway the preceptor to seeing you as an asset rather than a burden.

Try not to get frustrated if you have a new preceptor daily and you are repeating the same small tasks each day. Your preceptor needs to see that you are competent doing these tasks in order to build trust.

If bullying does occur, try to raise the topic with the preceptor in a nice manner. However, this is way easier said than done. Don’t suffer in silence. I’d recommend speaking to either the charge nurse or your nursing school clinical mentor if an issue arises. And don’t leave it until it’s too late to solve.

Also, try not to lose focus on the real reason why you are there.

Top tips for getting along with your preceptor

Discuss your weekly goals and objectives

Letting your preceptor know your weekly goals is essential as it gives them direction on what they need to teach you. Tell them what you’re not so confident in doing and what you would like to learn, so they can make sure you get hands-on practice.

Give them feedback on what you enjoyed learning and what you found helpful

Preceptors like to hear feedback just as much as students do. Let them know if they are doing a good job and ask them for feedback too. For example: “Did I do this well? or “What can I do better next time?”

Answer call bells and phone calls

Show initiative by answering not only your call bells but also other nurses’ call bells. And, if you are near the phone, answer phone calls too. There is nothing more frustrating to staff than seeing a student sitting next to a ringing phone and not answering it.

Answer the phone professionally by introducing yourself and naming the ward. Always take a message or pass the phone on. And always remember to report information back to your nurse.

Ask questions and show you are interested in being there

Instead of clock-watching, show that you’re willing and excited to be there learning. When drawing up medications or doing an assessment, ask reasonable questions that show you have insight and critical thinking skills. For example, ask why something is happening and what the outcome will be, as this shows forward thinking.

Home baking

Home baking works a treat! This may seem like a bribe, but it really is a great way to show your appreciation for your preceptor’s support and time.

Author: Mady Watt is currently a third-year nursing student at the University of Auckland’s School of Nursing.

NB First published online September 21. Re-published October 27 in Issue 5 of Nursing Review.

]]>Our hapori (community) is also renowned for its thriving tourism industry that attracts global recognition. Our cultural capital is our hapū, iwi and marae, which have stood resolute against the test of population decline, political hegemony and oppressive legislation (since the signing of Te Tiriti o Waitangi in 1840).

Recently our community of Fordlands hit the national headlines. To our communal shame, the Rotorua suburb ‘boasts’ significant deprivation, with the New Zealand Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD)1 reporting that Fordlands is the most socio-economically deprived neighbourhood in Aotearoa/New Zealand.

In contrast, and despite the 2011 Christchurch earthquake and its aftermath, the Christchurch suburb of Merivale was found by IMD to be the neighbourhood with the most advantages and least deprivation.

Inequity in action: Fordlands and Merivale

What, if anything, do these findings have to do with health equity, one might ask? Everything, is the only plausible answer!

Starting with Fordlands, the 2013 census data indicates a population of about 1,700. People in the community are mostly Māori. About 45 per cent have no qualifications; almost the same percentage have a level 1-6 qualification, and the predominant occupation is labourer. The average income is between $10,000 and $20,000 per annum; 60 per cent of families in Fordland are sole parents, and most live in rented dwellings. The neighbourhood has one block of corner shops, including a Four Square supermarket and a liquor store.

There are two general practices (seven doctors) near Fordlands – one is a 40-minute walk and the other is almost an hour’s walk. Neither practice is on the bus route. The children’s parks are minimal, and a far cry from other parks in the advantaged areas of Rotorua. A gang presence is not uncommon, making parents think twice about whether riding a bike in their neighbourhood is safe2.

Merivale’s census data indicates that most of the advantaged suburb’s about 2,700 people are European; 23 per cent have a degree and they earn in excess of $70,000 per annum.

A property search comes up with descriptions like ‘architecturally designed splendour, impeccable landscaping and an array of shopping facilities’.

Another search reveals at least five general practices (25 doctors); most practices can be reached by foot in roughly five to 10 minutes, plus there is a private hospital to boot. Not only are the people of Merivale spoilt for GP choice, they also reside in a health-enhancing environment.

Whitehead’s widely used definition of health inequity is “health inequalities that are avoidable, unnecessary and unfair are unjust”.

Braveman broadens the definition to argue that health equity is the absence of disparities for socially disadvantaged populations that are persistently exposed to systemic discrimination within a society.

A health equity lens would suggest that Fordlands residents’ disproportionately low share of resources is unfair, avoidable and unjust. In contrast, the already advantaged people of Merivale have greater access to government-funded primary health care and attractive local amenities.

Being healthy, it seems, is a whole lot easier when you live in areas of affluence.

Strengths, lessons and solutions?

You can argue that the system and structures are skewed favourably towards the people living in Merivale, not Fordlands.

This bias is avoidable, and ‘disrupting’ the status quo is within the remit of policy decision-makers and nurse leadership. It is remiss to blame individuals; instead we must always apply a critical and health equity lens on the system and the, at times invisible, bias towards privilege.

We could also learn from Rotorua’s main industry, tourism – an industry reliant on attracting people by providing services that meet tourists’ wants, needs, cultural worldview, preferences and desires. Understanding these factors is tourism’s core business and it unashamedly moulds itself to fit its target populations. To do otherwise would bankrupt an entire industry.

Arguably, the health system – with DHB budget blowouts and burgeoning demand outstripping supply – is an industry near bankruptcy. Taking a lesson or two from tourism seems both logical and sensible.

Another strength for Rotorua is its marae: focal points for whānau, hapū and iwi and places where Māori take reo, kawa and tikanga for granted. Whakapapa connects individuals, and from marae a sense of belonging is affirmed. Roles and responsibilities are also equally valued, which is critical to sustaining livelihoods.

But how are these strengths reflected in the design of our systems? And, importantly, are we truly ready to design systems that move us closer to health equity by meeting the needs of people most in need?

Author: Sonia Hawkins is a College of Nurses Aotearoa board member and Director Consultant for Te Pani Limited.

]]>But that doesn’t mean joy in work is impossible, says the Massachusetts-based Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI). In fact, it argues, improving joy in work is “possible, important and effective” as joy impacts not only on staff satisfaction but also on patient experience, quality of care and an organisation’s performance.

The institute sought to put its theory into action with a series of innovation projects in 2015-16 involving hospitals and health organisations in both the United States and the United Kingdom – including the American Association of Critical Care Nurses – and earlier this year published the resulting IHI Framework for Improving Joy in Work.

Dr Donald Berwick, IHI’s president emeritus, admits that joy in work sounds “flaky”. And, as he writes in a foreword to the 42-page framework document, the first feedback he received to suggesting joy in work should be a strategic goal for health organisations was “Get real!”

He acknowledges getting through the day is probably a more common goal in “inevitably stressed” work environments where “truly good people try hard to cope with systems that don’t serve them well, facing demands they can, at best, barely meet”. But the research literature is there that joy is both possible and important for the healing professions.

Why focus on joy in work?

Recent US studies found that 33 per cent of registered nurses seek another job within a year and 50 per cent of doctors report symptoms of burnout.

The institute decided that part of the solution was to focus on steps to restore joy to the healthcare workforce through a practical framework. It did a scan of the current published literature on engagement, satisfaction, and burnout; carried out interviews and site visits based on the literature scan; and worked with 11 health and healthcare systems in a two-month prototype programme testing steps, refining the framework, and identifying ideas for improvement.

The report – two of its six authors are nurses – says focusing on joy in the “physically, intellectually and emotionally demanding” health professions was important for three reasons.

Firstly, it says joy is one of healthcare’s greatest assets and looking at assets – and not just the health system’s deficits and gaps – may help find a solution to burnout. “Healthcare is one of the few professions that regularly provides the opportunity for its workforce to profoundly improve lives,” says the report. “Caring and healing should be naturally joyful activities.”

The second reason was that joy was more than the absence of burnout – it was also about having meaning and purpose. “By focusing on joy through this lens, healthcare leaders can reduce burnout while simultaneously building the resilience healthcare workers rely on each day.”

Finally, having joy in work can be seen as a fundamental right. The report authors point to the work of W Edwards Deming, the ‘father of quality management’, who said, “Management’s overall aim should be to create a system in which everybody may take joy in [their] work.”

The report says there is also a strong business case for improving joy, though it acknowledges there is not a single validated measure for joy in the workplace. But the business case for joy in work draws on outcomes including staff engagement, satisfaction, patient experience, burnout and turnover rates which in turn have been linked to greater professional productivity, lower turnover rates, improved patient experience, outcomes and safety resulting in lower costs.

“Perhaps the best case for improving joy is that it incorporates the most essential aspects of positive daily work life,” says the report. “A focus on joy is a step toward creating safe, humane places for people to find meaning and purpose in their work.”

Taking action on joy

Creating joy and engagement in the workplace is a key role of effective leaders, believes the Institute.

But it says in developing the framework it became evident that leaders often find it challenging to see a way to move from the current state to joy in work. This led to the ‘Four Steps for Leaders’ (see box) to help guide them in: finding out what matters to their staff, identifying impediments to joy, taking a systems approach to addressing those barriers, and testing whether the approaches are working.

An example from one of the framework prototype initiatives was a hospital inpatient unit deciding to focus on improving teamwork by testing introducing change-of-shift huddles to the unit’s various teams until the nurses involved established the best time, what to focus on and who would lead the huddle. By the end of four months, 90 per cent of teams on the unit were conducting daily huddles and engagement scores had risen by 30 per cent.

Another example was staff at the University of Virginia School of Nursing who identified a strong desire not to feel the pressure to respond to work emails when on time off. A small group of staff tested a small change – stopping sending email to staff during their time off – and the positive benefits led to it being expanded to all employees.

The paper says the ‘Four Steps for Leaders’ do not ignore the larger organisational issues, or “boulders” that exist, such as the impact of electronic health record functionality on clinicians’ daily work, or workload and staffing issues.

“Rather, the steps empower local teams to identify and address impediments they can change, while larger system-wide issues that affect joy in work are also being prioritized and addressed by senior leaders. This process converts the conversation from ‘If only they would …’ to ‘What can we do today?’”

The institute also created a framework that sets out the nine core components they believe contribute to a happy, healthy, productive workforce.

With Maslow’s hierarchy of needs in mind, it identified that there were five fundamental human needs that must be met to improve joy in work. These are: physical and psychological safety; meaning and purpose; choice and autonomy; camaraderie and teamwork; and fairness and equity.

“While all five of these human needs will not be resolved before addressing local impediments to joy in work, actions and a commitment to addressing all five will ensure lasting results,” says the report.

The framework and steps aim to help health leaders start on the path to more joy in the workplace and less burnout – a path that the institute believes is worth following for both the benefit of staff and patients.

“The gifts of hope, confidence, and safety that healthcare should offer patients and families can only come from a workforce that feels hopeful, confident, and safe,” says Berwick. “Joy in Work is an essential resource for the enterprise of healing.”

He adds that leaders who use the framework “might well find that the joy it helps uncover is, in large part, your own”.

Four Steps for Leaders (towards fostering joy in the healthcare workforce)

- Ask staff, ‘What matters to you?’

- Identify unique impediments to joy in work in the local context.

- Commit to a systems approach to making joy in work a shared responsibility at all levels of the organisation.

- Use improvement science to test approaches to improving joy in work in your organisation.

IHI Framework for Improving Joy in Work

- Physical and psychological safety: Do people feel free from physical harm? Including work-related injuries, infections and violence? Do they feel secure and free to express relevant thoughts and feelings, ask questions, admit mistakes or speak up about unsafe conditions?

- Meaning and purpose: Do people feel that the work they do makes a difference?

- Choice and autonomy: Do people feel they have a choice and voice in the way things are done?

- Camaraderie and teamwork: Do people feel like they are part of a team and have mutual support and companionship?

- Recognition and rewards: Is there meaningful recognition of people’s contribution? Are team accomplishments celebrated?

- Wellness and resilience: Is the health and wellness of all employees valued including cultivating personal resilience, stress management, an appreciation of work/life balance and provision of mental health support?

- Participative management: Do leaders involve and engage others before implementing change? Keep individuals informed of future changes that may impact on them? Do they consistently listen to everyone – not only when things are going well?

- Daily improvement: Does the organisation use improvement science to identify, test, and implement improvements to the system or processes?

- Real-time measurement: Do the measurement systems used enable regular feedback to facilitate ongoing improvement?

- Source:Perlo J et al (2017) IHI Framework for Improving Joy in Work. (IHI White Paper) Cambridge, Massachusetts: Institute for Healthcare Improvement. (Available online at ihi.org.)

PROs include: Great starting point for parents on information for caring about their babies in care; attractive app; can create own baby’s profile; users can connect to others through app community features.

CONS include: Some of the medical terms are difficult to understand; only brief information on topics so parents still need to look further for more in-depth information on important topics.

Full app review at www.healthnavigator.org.nz/app-library.

The NZ App Project: Health Navigator, a health website run by a non-profit trust, is using technical and clinical reviewers to develop a New Zealand-based library of useful and relevant health apps. Nurses are invited to support the project by either recommending consumer-targeted health apps for review and/or offering to be app reviewers. Email

[email protected] to find out more.

Fall prevention specialists from the UK, Australia and New Zealand came together in September to discuss and share approaches to reducing harm from falls during the Health Quality & Safety Commission’s tri-nation forums in Auckland and Wellington.

In recent decades, fall rates in hospitals and other inpatient settings have often been viewed as a nurse-sensitive indicator of the quality of patient care – or lack of quality when nursing is understaffed and under pressure.

But Dr Frances Healey, a nurse and deputy director of Patient Safety for National Health Service (England), says framing falls as a nursing problem does patients no favours.

“As actually we know that some of the key risk factors for people who fall in hospital are undetected medical causes, dementia that has not been confirmed, inappropriate medication prescribing, and poor fluid retention management.”

So the solutions – or causes – may not be nurse-sensitive. “All of our work in England has been very much based on reframing falls prevention as a totally multi-disciplinary problem,” says Healey. “I’m speaking as a nurse and I’m not for one moment denying the criticality of nurses within the team.”

She says they now regard falls as a symptom rather than just an accident. Tri-nations forum colleague Lorraine Lovitt, the lead for the New South Wales fall prevention programme, uses the analogy of seeing falls as the ‘canary in the mine’ that tells you something wider is amiss with the patient.

Julie Windsor, the patient safety clinical lead for older people for NHS (England), says at least 400 risk factors have been identified for falls. “So you can’t just say they [the risk factors] are all in the nursing arena – because they never will be and they’re not,” says Windsor who – like Healey and Lovitt – is a nurse herself.

“Instead it is identifying for each individual person what their risk factors are and then working out how these can be resolved or best managed.”

Healey says that is not to say that nurse staffing levels are not a factor.

“Of course we’d say it makes complete common sense that if a patient is going to call for help, needs help and you don’t have enough nurses to answer the call, of course that’s going to cause a problem.” But she says there are better tools for measuring whether staffing is adequate to meet patient acuity and demand than using falls as a nurse-sensitive indicator.

She says the point of reporting incidents, like a fall or medication error or misdiagnosis, is to learn from them and, as deputy director of Patient Safety, she wants to encourage reporting of incidents so that learning can happen. “If you don’t report it – how can you learn from it? So to then use them [incident reports] to say you are not a good quality provider is detrimental and counterproductive to the whole purpose.”

Healey says the NHS does publish incident rates per provider, but the regulators are most concerned when reported incidents are very low and classify them as “potential underreporting of safety incidents”. “It is not perfect, but is a far healthier way, perhaps, of encouraging it [reporting].” Likewise, she says labelling falls as primarily a nursing quality indicator “can’t help us with the message that we need the whole team to help our patients”.

Lovitt says in New South Wales hospitals one interdisciplinary approach they are taking is ‘safety huddles’ where nurses can flag the risks that showed up in their patient screenings – like delirium or a memory issue – and take a team approach to managing them.

Early last year the results were published in the British Medical Journal (Anna Barker et al.) of a randomised controlled trial in six Australian hospitals of a nurse-led ‘six-pack’ bundle of nursing interventions to reduce fall injuries. The 12-month trial found no difference in falls or injury rates between the intervention and the control group.

In an online letter to the BMJ, Julie Windsor wrote that while the results might at first appear disappointing to the many frontline nurses and nurse leaders who had “wholeheartedly and valiantly” tried to make improvements, it was now time to move on. “[It is] time now to re-energise and look at innovative and novel quality improvement initiatives that include all professional groups,” she said.

Because nursing can’t do it alone.

]]>“While empathy and sympathy are both reactions to the plight of another person, sympathy is just a feeling of pity for their misfortune. Empathy is like walking a mile in someone else’s shoes; sympathy is just being sorry that their feet hurt.”

Levett-Jones, Professor of Nursing Education at the University of Technology, Sydney (UTS), addressed the recent Australasian Nurse Educators Conference on why empathy still matters to nurses and the patients they care for, and how her research shows that empathy should – and can – be taught.

The three levels of empathy

Levett-Jones explains that there are three levels of empathy and some levels come more easily than others.

The first level is affective empathy, which is the easiest form of empathy as nearly everybody, except narcissists, is hardwired to feel empathy for misfortunes they can relate to – particularly if the person suffering that misfortune is similar in sex, age, nationality or ethnicity to themselves.

The next level is cognitive empathy, which requires more than the empathetic imagination necessary for affective empathy, as it requires empathetic intelligence to attempt to see the world through another person’s eyes.

Levett-Jones says cognitive empathy also requires a non-judgmental stance, which is a challenge to everybody, but particularly for nurses. “I’m a proud nurse, but I’ve also sat in many handovers when nurses have made judgmental statements like: ‘[That’s just] drug-seeking behaviour’ and ‘They are just a whinger’.

“If we could look into each other’s eyes and understand the unique challenges that each of us faces, we would treat each other with much more empathy, patience, tolerance and care,” says Levett-Jones.

The third and highest level of empathy is behavioural empathy, which steps empathy up a further notch and requires effort, intelligence and deliberate practice to develop and communicate empathetic concern for another and a readiness to put that empathy into action. Levett-Jones says many regard behavioural empathy as being synonymous with compassion.

Empathy in decline

Interest in empathy has never been higher, with double the number of books written on the subject in the past five years than in the previous years, says Levett-Jones. Likewise, the number of web searches on the topic have tripled.

But while interest is high, research indicates that empathy itself is going through new lows, with Levett-Jones quoting one large retrospective study of American college students showing that empathy has declined by more than 40 per cent over the past 30 years, with the steepest decline being this century. Screens and social media are thought to be one possible cause of the decline, with young people spending increasing amounts of time reading and sending emoticons and emojis, rather than reading real faces.

Nursing and medicine is not immune to this decline, with a body of evidence showing that fresh-faced nursing and medical students’ empathy levels decline by up to 50 per cent from when they start their degrees to when they finish them. Levett-Jones says some of the reasons are believed to be prioritising technical and procedural skills over values like empathy, limited attention to teaching and assessing empathy skills, and students being desensitised and suffering compassion fatigue from being exposed to human suffering without appropriate preparation or support.

“We kind of got the hunch that if we threw nursing students into situations that obviously were intended to generate an empathic response, it would happen,” says Levett-Jones. “It actually doesn’t, as what happens is that students are in survival mode and they can shut off.”

Does empathy still matter?

Does it matter whether nurses are empathetic? Most definitely yes, believes Levett-Jones, with empathy being a key component of all therapeutic relationships. Demonstrating empathy is also seen as a key competency indicator by the Nursing Council of New Zealand.

Levett-Jones says there is compelling research that empathetic engagements with patients have a major impact – from decreasing levels of depression and distress, increasing adherence to treatment plans and improving physiological outcomes, from tissue healing to blood pressure. “What medication, technology or high-level medical intervention could influence all of those outcomes?” she says.

Research also indicates that having empathy is a plus for health professionals as it enhances their clinical reasoning ability and is linked to job satisfaction, resilience and coping skills. Other research has indicated that nurses are at a higher risk of burnout, distress, depression and attrition if they don’t have the required level of empathy skills.

“There has been a lot of hype about the fact that nurses get compassion fatigue if they are too empathetic – if they care too much – but actually the opposite is true,” says Levett-Jones. “Empathy is actually energising; it is fulfilling and it is satisfying. A lack of empathy is actually soul-destroying and saps our energy.”

Sadly, she says, it has been demonstrated that the people who get the least empathy from healthcare professionals are those who need it most – that is, people from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds, aboriginal people (in Australia), and people with physical or intellectual disabilities, mental illnesses or lifestyle-related diseases.

Yes, empathy can and should be taught

Empathy, therefore, matters to both nurses and their patients, concludes Levett-Jones; it matters enough that nursing shouldn’t rely on the hope that the people drawn to the profession are intrinsically empathetic.

She quotes from the UK’s 2013 Francis Report on patient neglect in Mid-Staffordshire hospital, which, amongst its findings, said: “In addition to safety, healthcare needs to have a culture of empathy. Such a priority cannot be assumed, it needs to be the subject of training.”

Also guiding the nursing education professor’s philosophy is Aristotle’s quote that “educating the mind without educating the heart is no education at all”.

“One of the statements that runs around my mind the whole time is that if we ‘capture their hearts, their minds will follow’,” says Levett-Jones. “So I never, ever, tell my students a whole series of facts about a disease. I always tell them about a person with that disease and their life story in a way that hooks the students’ imaginations and attention.”

Amongst the methods of teaching empathy is using tools, such as film, art and literature, that give students insights into the perspectives of people they may not normally encounter or engage with in meaningful ways. Movies such as The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (about a man with locked-in syndrome) and Wit (a challenging film about a woman dying of ovarian cancer) are amongst the teaching tools in Levett-Jones’ toolbox.

But she says a review of four recent randomised, controlled trials indicates that experiential simulations – where students are asked to ‘stand in the patient’s shoes’ – were the most beneficial for teaching empathy. Levett-Jones has developed several such simulations herself to put students in the shoes of some of those patients who need empathy the most, but receive the least – including CALD patients, who are twice as likely to experience serious adverse events in hospital as English-speaking people.

Teaching empathy by simulation scenarios

Levett-Jones’ cultural empathy simulation puts nursing students in the scenario of being a backpacker who becomes a bedridden patient in the hospital ward of a developing country.

Wearing a 3D virtual reality visor, they watch a 3D video unfold where everything is alien to them – the hospital environment, the language and the clinical practices show cultural behaviours and symbols unfamiliar to an Anglo-Celtic Australian.

The research tested the students using several standard empathy scale tests. A cultural competency scale test before and after the simulation found significantly higher scores after the simulation. Students also told researchers that they were amazed how quickly a 10-minute video had changed their views and how they now had an understanding of being an outsider.

The second major simulation scenario came about after Levett-Jones become concerned about students’ attitudes to people with disabilities. A trigger for the scenario was the unempathetic treatment of a nursing colleague’s teenage daughter, who had been hospitalised for three months after a brain injury.

The resulting disability simulation put second year students either into the role of a person with a brain injury (following a car accident) or of a rehabilitation nurse. The ‘patient’ wore a special hemiparesis suit that replicates the experience of aphasia, dysphagia, and being blind and weak on one side of their body. The ‘nurse’ comes and helps to dress the ‘patient’ then takes them for a walk, before leaving them to sit at an outside table in a busy public area for five minutes (while the ‘nurse’ watches from a distance).

Levett-Jones says in nearly all cases people turned away from the ‘patient’ and didn’t offer to pick up a dropped walking stick or help them to stand.

The findings from the research showed a significant increase in empathy pre and post-simulation for the ‘patient’ student, but somewhat surprisingly the increase in empathy pre and post-simulation was even higher for the students who played the ‘nurse’ role.

It appeared that watching people being indifferent to their patient had really challenged them and the test for the teachers was to ensure the students received an empathetic and not a sympathetic or pitying response.

But simulation has shown that it is possible to teach future, and current, nurses to feel increased empathy for people whose lives are beyond their own experiences.

“We have such an opportunity with undergraduate students, new grads and with other nurses to really challenge their level of empathy,” says Levett-Jones. “To really do things that can increase empathy because – as I have shown you – empathy has a profound impact on patient outcomes.”

]]>Reading this article and undertaking the learning activity is equivalent to 60 minutes of professional development.

This learning activity is relevant to the Nursing Council registered nurse competencies: 1.1, 1.4, 2.9, 4.3

Learning outcomes

Reading and reflecting on this article will enable you to:

- increase familiarity with the Code of Conduct standards for professional nursing conduct and behaviour

- practise applying the principles and standards of the Code

- raise awareness of the appropriate approach for health professionals towards professional boundaries, social media and electronic communications

- locate and review guidelines that underpin nursing practice.

Introduction

Three documents from the Nursing Council of New Zealand (NCNZ) provide a comprehensive guide to nursing professional conduct and behaviour in New Zealand.

The documents span all scopes of practice3,4,5 settings and specialties. Every nurse should be very familiar with these documents and copies of them should be easily accessible in all work settings. This article provides an overview of each document with useful tips and examples to prompt reflection. It does not cover everything OR replace the need to read the documents.

The Code of Conduct² is the primary document, with the two additional documents Guidelines: Professional Boundaries⁷ and Guidelines: Social Media and Electronic Communication⁸, providing extra information and guidance.

The Code of Conduct

“The Code is a set of standards defined by NCNZ describing the behaviour or conduct that nurses are expected to uphold. The Code provides guidance on appropriate behaviour for all nurses and can be used by health consumers, nurses, employers, NCNZ and other bodies to evaluate the behaviour of nurses²”.

The Code promotes four core values; respect, trust, partnership and integrity. These values are referred to throughout the eight principles and the 81 standards.

Code principles

- Respect the dignity and individuality of health consumers (10 standards).

2. Respect the cultural needs and values of health consumers (10 standards).

3. Work in partnership with health consumers to promote and protect their wellbeing (8 standards).

4. Maintain health consumer trust by providing safe and competent care (12 standards).

5. Respect health consumers’ privacy and confidentiality (8 standards).

6. Work respectfully with colleagues to best meet with health consumers’ needs (10 standards).

7. Act with integrity to justify health consumers’ trust (14 standards).

8. Maintain public trust and confidence in the nursing profession (9 standards).

The Code also contains guidance on: professional misconduct, escalating concerns, fitness to practise and public confidence.

| Code of Conduct Example 1: | “I’m worn out working two jobs; if it’s quiet I sleep through the night shift – I tell the HCA to wake me if anything major happens.” |

| Specific problems |

|

| Standards to consider | 4.2 Be readily accessible to health consumers and colleagues when you are on duty.

6.4 Your behaviour towards colleagues should always be respectful and not include dismissiveness, indifference, bullying, verbal abuse, harassment or discrimination. 6.8 When you delegate nursing activities to enrolled nurses or others, ensure they have the appropriate knowledge and skills, and know when to report findings and ask for assistance. 7.3 Act promptly if a health consumer’s safety is compromised. Other standards that may also apply here include 4.10 and 6.1. |

| Code of Conduct Example 2: | “I help my neighbour out by checking her husband’s clinical notes for his results as he never gets around to telling her; she says he doesn’t mind her knowing. He isn’t my patient but I can easily access his information.” |

| Specific problems |

|

| Standards to consider | 5.1 Protect the privacy of health consumers’ personal information.

5.2 Treat as confidential information gained in the course of the nurse-health consumer relationship and use it for professional purposes only. 5.6 Health records are stored securely and only accessed or removed for the purpose of providing care. 5.7 Health consumers’ personal or health information is accessed and disclosed only as necessary for providing care. Other standards that may also apply here include 5.5. |

Guidelines: Professional boundaries

Nurses must remember that within any professional relationship there is a significant power dynamic in play.

This dynamic – and the boundaries of professional practice – can be tested as nurses seek to support and empathise with patients and patients’ families. Patients and their families will often feel vulnerable and seek to increase a relationship with a nurse, feeling they can trust the nurse to have their best interests at heart.

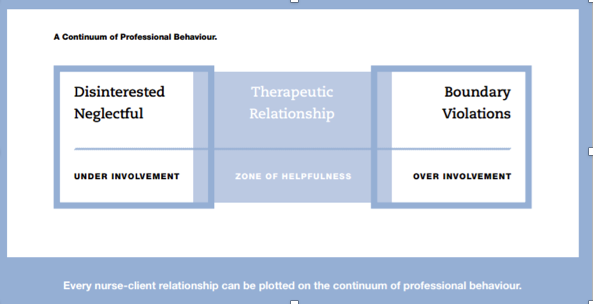

The professional boundaries document highlights the need for nurses to be responsible for maintaining a professional boundary in all aspects of the nurse-patient relationship, and gives examples that can occur across nursing. The balance required is illustrated using the ‘Continuum of Professional Behaviour’ diagram (see Figure 1).

The guidelines also contain clear and effective ‘questions for reflection’ on professional boundaries:

- Is the nurse doing something the health consumer needs to learn to do themselves?

- Whose needs are being met – the health consumer’s or the nurse’s?

- Will performing this activity cause confusion regarding the nurse’s role?

- Is the behaviour such that the nurses will feel comfortable with their colleagues knowing they had engaged in this activity or behaved in this way with a health consumer?

Key areas for nurses to be aware of are covered, including: caring for close friends or family; sexual relationships with patients or former patients or patients’ partners/family members; gifts, bequests, loans; financial transactions; power of attorney; and concluding professional relationships.

Boundary transgressions have resulted in some serious breaches and consequences. If you become aware of a colleague’s boundary transgression, the document provides advice on how to proceed.

| Professional boundaries Example 1: | “I house-sit for the family of a long-term patient. I had told them I don’t like my current flat and want to get away. They trust me and even pay me $50 a week for expenses.” |

| Specific problems |

|

| Standards to consider | 7.5 Act in ways that cannot be interpreted as, or do not result in, you gaining personal benefit from your nursing position.

7.6 Accepting gifts, favours or hospitality may compromise the professional relationship with a health consumer. Gifts of more than a token value could be interpreted as the nurse gaining personal benefit from his/her position, the nurse taking advantage of a vulnerable health consumer, an attempt to gain preferential treatment, or an indicator of a personal or emotional relationship. 7.13 Maintain a professional boundary between yourself and the health consumer and their partner and family, and other people nominated by the health consumer to be involved in their care. 8.8 Ensure you only claim benefits or remuneration for the time you were employed or provided nursing services. Other standards that may also apply include 7.8, 7.10, 7.11 and 7.12. |

Guidelines: Social media and electronic communication

Electronic communication is part of everyday life for most people, including nurses. Health professionals have a responsibility to take a more considered approach to what they communicate and to understand the consequences of what is sent in an email, text or posted online.

The social media guideline highlights specific areas related to breaching confidentiality and privacy, either intentionally or unintentionally, working respectfully with colleagues and employers, using professional language at all times, working with integrity and maintaining public trust and confidence in the nursing profession.

| Social media Example 1: | “If I post a photo or story about work on social media, I always keep the privacy setting to just my friends and I never use patient names.” |

| Specific problems |

|

| Standards to consider | 5.2 Treat as confidential information gained in the course of the nurse-health consumer relationship and use it for professional purposes only.

5.8 Maintain health consumers’ confidentiality and privacy by not discussing health consumers, or practice issues in public places including social media. Even when no names are used, a health consumer could be identified. 6.4 Your behaviour towards colleagues should always be respectful and not include dismissiveness, indifference, bullying, verbal abuse, harassment or discrimination. Do not discuss colleagues in public places or on social media. This caution applies to social networking sites e.g. Facebook, blogs, emails, Twitter and other electronic communication mediums. 8.1 Maintain a high standard of professional and personal behaviour. The same standards of conduct are expected when you use social media and electronic forms of communication. |

| Social media Example 2: | “I needed to place Mum in a rest home. I looked for the nurse manager of the nearest one online and his social media account was full of photos of his partying and bad language.” |

| Specific problems |

|

| Standard to consider | 8.1 Maintain a high standard of professional and personal behaviour. The same standards of conduct are expected when you use social media and electronic forms of communication. |

Remember!

- Employers, employees, staff, colleagues, patients and their family members may well check your online presence.

- Privacy settings do not prevent the sharing of information. Anything you send to another person can be copied and shared with others.

How do I use the documents if I’m concerned about a colleague?

Practice issues will often spread across a number of principles and standards. Check through the Code of Conduct and also refer, as required, to the two guideline documents.

- If you see a professional practice situation that concerns you to the degree that you think you need to refer your concerns, write it down.

- Refer to the Code and/or the social media and/or professional boundary documents.

- Review each principle and each standard to see where the issues you have identified fit.

- Note down the relevant standard(s).

- Follow your organisation’s professional practice reporting process.

Note: Check with your employer and employer policies in the first instance. If you then consider notifying the Nursing Council, ensure that what you have identified is a professional practice issue and not an employment issue.

In conclusion

These three documents, which are freely available on the NCNZ website, provide comprehensive guidance for professional nursing practice. Used alongside the relevant nursing competencies, they provide nurses, employers and the public with a clear framework for all aspects of professional nursing behaviour and conduct.

QUICK CODE CHALLENGESee if you can identify which principles and standards could be relevant to these three scenarios. |

|

| Challenge 1 | One of the clinic patients is Māori and she often requests that whānau come into the clinic room with her. It’s absolutely not appropriate in my view and makes me feel I’m being watched, so I’ve started saying no. |

| Challenge 2 | One of my colleagues shouts at residents who are hard of hearing. She really talks down to them and doesn’t bother explaining when she is doing something as she says it just takes ages. They don’t get a choice. |

| Challenge 3 | One nurse I work with was quite rough and demeaning to a patient in the emergency room and didn’t explain any of the care given. The patient was under police escort. I’ve seen this nurse behave this way many times with patients who are prisoners with guards or under police escort. |

Download the learning activity here >>

Useful tip

Refer to the below THREE documents if you are dealing with practice issues:

- Code of Conduct²

- Guidelines: Professional Boundaries⁷

- Guidelines: Social Media and Electronic⁸

The document may help you to identify or approach a situation. They can even provide helpful wording for framing feedback.The three documents, plus many more standards and guidelines are freely available to download from www.nursingcouncil.org.nz.

Recommended resources

- Health and Disability Commissioner (2009). Code of health and disability services. Consumers’ rights. Retrieved from www.hdc.org.nz/the-act–code/the-code-of-rights.

- The NCNZ’s Code of Conduct and Guidelines are freely available to download at www.nursingcouncil.org.nz/Nurses/Code-of-Conduct.

- The College of Nurses (NZ) website for Professional Support Guides on bullying and practice issues at www.nurse.org.nz/powerpoint-presentations.html.

- Worksafe NZ: Bullying Prevention Toolbox at www.worksafe.govt.nz/worksafe/toolshed/bullying-prevention-toolbox.

About the author

Liz Manning RN, BN, MPhil (Nursing), FCNA (NZ) is the director of Kynance Consulting and provides project management services, professional nursing supervision, coaching, mentorship and portfolio development support.

This article was peer reviewed by:

Cheryl Atherfold RN MHSc (Nurs) FCNA (NZ), who is an associate director of nursing practice and education at the Waikato District Health Board.

Erin Meads RN, BN, PGDipAdvNsg is the director of nursing for the Auckland-based primary health organisation ProCare.

References

- COLLEGE OF NURSES (NZ) Inc (2017). Professional Support Guides. Retrieved from

www.nurse.org.nz/powerpoint-presentations.html - NURSING COUNCIL OF NEW ZEALAND (2012). Code of Conduct. Wellington: Author.

- NURSING COUNCIL OF NEW ZEALAND (2012). Competencies for Enrolled Nurses. Wellington: Author.

- NURSING COUNCIL OF NEW ZEALAND (2017). Competencies for the nurse practitioner scope of practice. Wellington: Author.

- NURSING COUNCIL OF NEW ZEALAND (2007). Competencies for Registered Nurses. Wellington: Author.

- NURSING COUNCIL OF NEW ZEALAND (2011). Guideline: delegation of care by a registered nurse to a health care assistant. Wellington: Author.

- NURSING COUNCIL OF NEW ZEALAND (2012). Guidelines: Professional Boundaries. Wellington: Author.

- NURSING COUNCIL OF NEW ZEALAND (2012). Guidelines: Social Media and Electronic Communication. Wellington: Author.

- PRIVACY ACT (1993). Retrieved from

www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1993/0028/latest/DLM296639.html - WORKSAFE NEW ZEALAND (2017). Bullying Prevention Toolbox. Retrieved from

www.worksafe.govt.nz/worksafe/toolshed/bullying-prevention-toolbox.

The five-year Longitudinal Interprofessional (LIP) study, being run by the University of Otago in collaboration with Otago Polytechnic and the Eastern Institute of Technology, involves graduates from eight health professions (nursing, dentistry, dietetics, medicine, occupational therapy, oral health, pharmacy, and physiotherapy).

Lead researcher and physiotherapist Dr Ben Darlow says there is a real lack of data about how new health professionals adapt to the workforce and learn to work in healthcare teams. The LIP study will explore attitudes and skills related to interprofessional practice, as well as early career trajectories and influences on these.

The study involves whole year groups from each discipline and first surveyed the students before they started their final year of training (in 2015 or 2016) and continued with yearly surveys until their third year of professional practice (either 2018 or 2019). About 130 of the participants went through the Tairāwhiti Interprofessional Education (TIPE) Programme (based on the East Coast) and part of the research is comparing attitudes to collaborative team work between the TIPE graduates and the other graduates.

Darlow said keeping track of the graduates as they start work and keeping them engaged with the study was a real challenge, but also an exciting opportunity. To date it has had on average around an 80 per cent response rate to its annual survey of graduates. The next survey is due out in October, with the survey questions adaptable for graduates who may have changed clinical field, career or are taking a break.

Nurses make up 13 per cent of study participants. The average nurse participant age at graduation was 23 years old and 99 per cent were female.

Jennifer Roberts, head of EIT’s School of Nursing, said it was fortunate that TIPE allowed its nursing students the opportunities to learn alongside other health professional students, particularly as interprofessional health care and quality improvement is a key competence for registered nurses.

More information is at the study website lipstudy.researchnz.com.

]]>