Thousands of nurses have invested thousands of hours and, in a number of cases, thousands of dollars into postgraduate study.

There are many motivations, both personal and professional, for taking the postgraduate path, but as there is no automatic pay jump for nurses who complete a postgraduate certificate, diploma or master’s degree, immediate financial reward is probably not high amongst them.

Postgraduate study can open the door to career progression – for example, taking on an advanced practice role such as clinical nurse specialist, nurse practitioner or, more recently, nurse prescriber – or to other roles such as nurse educator and nursing school lecturer, and to positions in nursing management.

PDRP: Expert level allowances

There are national expectations that, before applying for expert level on most professional development recognition programmes (PDRPs), a nurse will have completed postgraduate study, or its equivalent. A nurse approved at an expert PDRP level receives:

- NZNO DHB MECA: an extra $2.16 an hour on base pay ($4,500 for a standard 40-hour week)

- NZNO PHC MECA: an extra $2.10 an hour on base pay rate

- PSA DHB Nurse MECA: an extra $2.88 an hour ($6,000 a year) N.B. Only for expert nurses approved by 1 October 2017; it then drops to $2.16 pro-rata.

Senior nurse pay scales

Postgraduate study can be an employment requirement for joining and progressing through the grades of a DHB’s senior nurse pay salary scale.

- NZNO DHB MECA: senior nurse salary scale $70,871 to $114,967

- PSA DHB Nurse MECA: senior nurse salary scale $75,013 to $113,486

Salary differences between nurses with graduate and postgraduate qualifications

The Ministry of Education has an ongoing project monitoring the income and employment trends for graduates by analysing the anonymous tax and tertiary education data of young people graduating from 2003-4 onwards.

The extensive data includes looking at the average top, mid and bottom income for young nurses 10 years after they have graduated with a nursing degree or with a postgraduate certificate or diploma in nursing. (No specific data is available for master’s degrees in nursing.)

N.B. The study focuses on young people, so 10 years after graduating these nurses will be aged roughly between 31 and 36 and a number may be working part-time so the income levels may reflect that.

Low to top nurse income range 10 years after graduating with:

- an undergraduate degree: $28,082 to $70,391

- a postgraduate certificate/diploma: $41,759 to $83,693.

Learning outcomes

Reading and reflecting on this article will enable you to:

- gain an understanding of the current knowledge of the physiology of sleep and its association with illness and healing

- consider steps to enhance patient sleep, including identifying poor sleep quality and advising patients on steps they can take to improve their sleep, and considering the institutional environment for sleep, therefore potentially improving health outcomes.

Reading this article and completing this ‘Appeared to sleep well’: How much sleep has your patient had and why does it matter? self-assessment learning activity is equivalent to 60 minutes of professional development.

NCNZ competencies addressed: Registered Nurse competencies: 1.4, 1.5, 2.1-2.4, 2.6,

2.8-2.9, 3.2, 4.1-4.3

Introduction

Of one thing you may be certain, that anything which wakes a patient suddenly out of his sleep will invariably put him into a state of greater excitement, do him more serious, aye, and lasting mischief, than any continuous noise, however loud.

(Florence Nightingale1, 1860, p. 44)

Sleep is defined as the “temporary state of relative unconsciousness from which an individual can be roused either by internal or external stimuli”2

(p. 105).

Since Florence Nightingale’s time1, nurses have recognised the importance of sleep to patients’ recuperation and wellbeing as well as nurses’ capacity to support patients’ sleep. Patients experiencing sleep deprivation or fragmented sleep develop complex physiological reactions that, with their other health conditions, result in poorer health outcomes, including increased hospital stays and delirium. However, nurses often rely on their own observations to assess sleep quality – an inherently unreliable process.

In this article we provide an overview of current understanding of the impact of sleep and sleep deprivation on recuperation for adults in institutional settings and argue for a whole-of-system approach to ensure that environments where patients sleep best meet their needs.

While we particularly mention sleep in institutional settings such as hospitals, the information is relevant for nurses working with patients in all areas and for nurses themselves, especially those who undertake shift work. We do not address the many sleep disorders in this article.

Sleep

Mrs Brown, aged 72, admitted today with a #NOF following a fall at home. While awaiting surgery, she is in traction in a six-bedded bay, with a PCA for analgesia. She usually cares for her husband who has mild dementia, and states that she sleeps lightly at home.

When Mrs Brown reports feeling exhausted the next day, what factors would you consider? What, if anything, could you change?

Sleep is a complex phenomenon and is vital for many bodily functions. Two processes are involved in sleep regulation: a homeostatic component of sleep pressure after periods of wakefulness, and circadian influences via the circadian body clock. The circadian body clock regulates all circadian rhythms including the sleep-wake cycle – periods of sleep and wakefulness over a period of approximately 24 hours2,3. Sleep patterns differ throughout life stages and change with ageing processes.

Normal sleep involves a sequence of complex physiological states controlled by the central nervous system (CNS) and associated with changes in many body systems. Sleep is a cyclical process with distinct physiological responses over the course of the sleep cycle.

There are two sleep states:

- Non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep (approximately 75% of sleep time).

- Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep (approximately 25 per cent of sleep time).

NREM sleep includes three stages N1–3, progressing from light to increasingly deeper sleep, when it becomes increasingly more difficult to rouse a person3,4.

REM sleep occurs at the end of these stages, and usually gets longer throughout the total sleep period.

Each full sleep cycle ranges from approximately 70 to 120 minutes, with an average of 90 minutes, and most adults have about five cycles over an eight-hour sleep with some brief awakenings between cycles. While asleep, the body undergoes processes of physiological and psychological conservation and restoration.

During NREM sleep stages, parasympathetic activity increases, sympathetic tone decreases and the release of human growth hormone aids epithelial and cell repair, while skeletal muscles relax, allowing the conservation of chemical energy for cellular processes. The basal metabolic rate falls, heart rate, breathing rate, muscle tone, core temperature and blood pressure all decrease.

REM sleep is important for cognitive restoration and is associated with changes in cerebral blood flow, increased cortical activity, increased oxygen consumption and cortisol release with alterations in heart rate, temperature, blood pressure and breathing rate. Most muscles become atonic during REM sleep. Increased cerebral blood flow is thought to aid memory storage, learning and concentration2.

All sleep stages are important to health; however, when unwell and in an unusual environment such as a hospital ward, individuals’ sleep patterns change in multiple ways, including with reduced sleep depth, increased sleep fragmentation, including more arousals, awakenings and limited REM sleep. A list of the factors that may disrupt a patient’s sleep cycle is included in Box 1.

Inadequate sleep – its effects

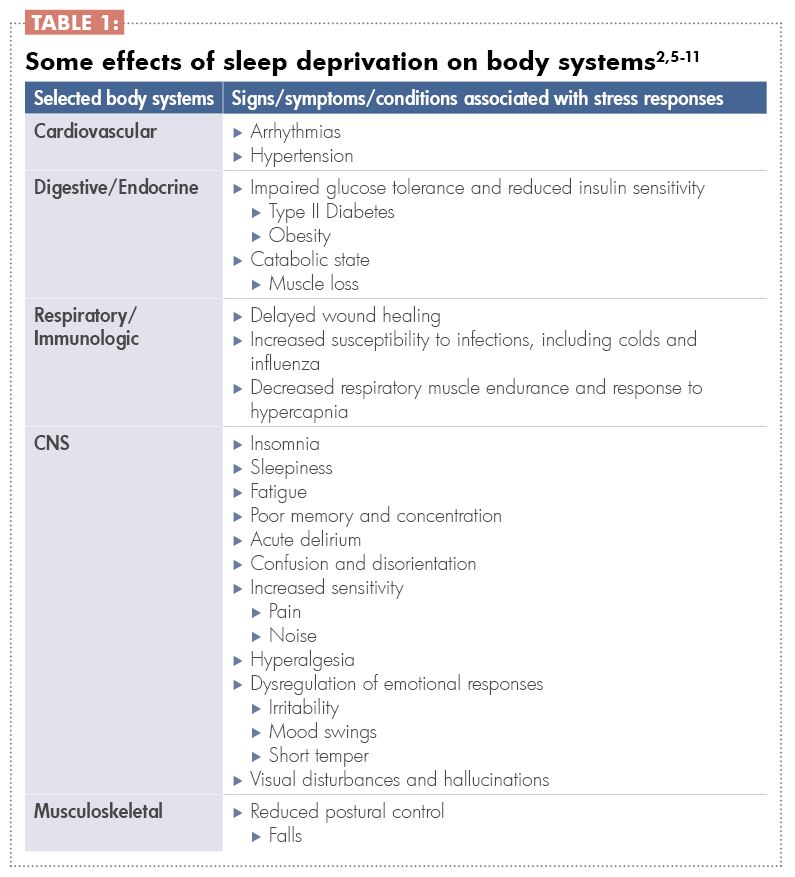

Sleep deprivation, either acute or chronic, causes a stress response that disrupts the key hormone release cycles normally linked to circadian rhythms, including the early evening melatonin release, the late-night release of growth hormone and the peak of cortisol release soon before waking naturally2 (see Table 1).

These effects of sleep deprivation and the stress response combine to contribute to poor health outcomes. Those outcomes include increased length of hospital stay, increased morbidity including nosocomial infections, and hospital-acquired injuries such as pressure injuries, poor wound healing, and mortality2,5,7. Specifically for hospitalised elders, these outcomes increase the risk of needing residential care post-discharge9.

Modifying the sleep environment

As shown in Box 1, many factors impact on sleep, and some are potentially modifiable by either the individual or the institution.

Research findings about sleep quality are consistent, with around 30 per cent of hospital patients reporting unsatisfactory sleep12. Firstly, patients’ sleep is often disrupted. In one study9, patients woke about 13 times per night. Secondly, sleep duration is short – about 3.75 hours per night in one study9. Thirdly, disruptions often mean that patients are woken mid-sleep cycle (of about 90 minutes).

There is the potential for patients to then experience disorientation (sleep inertia), depending on the stage of sleep from which they were awoken, the amount of sleep that they have had and the time of day they are woken13. Patients attempt to catch up on sleep during the day but this is largely unsuccessful6. However, research findings about other factors are more nuanced and contextual, such as the impacts of light and type of noise on sleep, the differences between sleeping in a single or multi-bed room, and even how much the hospital bed affects sleep9,14.

There is, however, much interest in how the environment can be modified and a number of approaches are being tested internationally. While many single approaches, such as ‘quiet times’ are tried, the most successful approaches are those that are whole-of-system, including consideration and management of all the work and of all the staff who affect what happens at night time in a ward or unit14. Successful approaches include a combination of the following activities:

- Agreed ‘quiet times’ when disturbances are limited and routine care activities are put on hold if possible. Those times are usually between 10pm and 6am.

- Lights automatically dimmed corresponding with quiet times.

- Shifting of the times for ‘routine’ cares and vital signs recording throughout the 24-hour period to limit disruptions at night.

- Reducing the prescription of medications given during quiet times, or shifting the times for administration (e.g. intravenous antibiotics).

- Limiting the administration of medications known to inhibit or impact on sleep to earlier in the day.

- Monitoring noise in corridors, with warning lights when a threshold is breached.

- Assessment and care planning so that patients who want to settle first at night are settled first.

- A night-time routine, including quiet music, lights gradually dimming.

- Care with the use of sedatives.

- Grouping of cares overnight 9,10,14.

Personalising sleep interventions

Individualised approaches to promoting sleep have also been researched. Interestingly, while individual patients may respond positively to these approaches, the evidence is quite weak and more research is needed11. The current evidence is strongest for massage, acupuncture, music, and natural sounds 5,11, and weak for ‘sleep hygiene’ (good sleep habits) and relaxation approaches11. However, there is also the opportunity for hospitalised patients to receive information at this time to aid their sleep at home.

Assessing sleep

Considering how important sleep is to healing and recuperation, attention to assessment of a patient’s sleep pattern is important. While sleep measurement is complex and reliant on tools such as EEG, sleep assessment includes understanding the person’s baseline sleep pattern and how the patient perceives their own sleep quality, questions about which are included in every nursing assessment. Standardised sleep assessment tools that are often only used in research could be used in everyday clinical practice12. These tools could replace nurses’ perceptions that are the most common assessment method. Nurses’ perceptions are highly unreliable, with nurses overestimating the perceived sleep quality8,12,15. It also results in the ‘appeared to sleep well’ record commonly seen in clinical notes.

One easy-to-use tool that, to date, has been mainly used in critical care units, the Richards-Campbell Sleep Questionnaire, includes five separate line measures of:

- Sleep depth (light-deep)

- Sleep latency (delay in falling asleep – fell asleep almost immediately)

- Awakenings (awake all night – awake very little)

Returning to sleep (when woken or waking, couldn’t get back to sleep – got back to sleep immediately)

Sleep quality (a bad night’s sleep – a good night’s sleep).

When used in research, another question is added related to the noise level in the environment15. Importantly, this tool requires patient self-report and is therefore a more valid measure of sleep.

Conclusion

The impacts of restful sleep cannot be overestimated and nurses are in a unique position to both monitor and promote sleep in institutional settings and to also support individuals at home. Patients who experience sleep deprivation exhibit poorer health outcomes, some of which are preventable, and identifying poor sleep and its causes are important steps in improving sleep health. There is much potential in a multi-pronged approach to modifying the sleep environment, combined with better use of assessment tools.

Download the learning activity here >>

Box 1:

What affects a patient’s sleep?

The individual, their health condition and responses

- Their normal sleep pattern.

- Current condition.

- Co-morbidities.

- Pain and discomfort.

- Anxiety.

- Pre-existing sleep disorders, such as apnoea.

- Age.

- Cultural needs, including whether sleeping in an environment with strangers or with

- people of other genders is appropriate.

Therapies

- Medications (e.g. steroids, diuretics).

- Indwelling devices (e.g. catheters, IV devices).

- Equipment (alarms, mechanical noises).

- Care interventions.

Environment

- Temperature, such as air-conditioned rooms.

- Noise.

- Disturbances.

- New environments, including hospital beds.

- Light.

- Presence of others in single or multi-bed rooms.

About the authors:

- Lesley Batten RN PhD is a senior researcher at Massey University, Palmerston North.

- Claire Minton RN MN is a lecturer and PhD candidate at Massey University, Palmerston North.

This article was peer reviewed by:

- Sally Powell RN MHSc (Clinical), a clinical nurse specialist in sleep health at Canterbury District Health Board’s Sleep Unit.

- Karyn O’Keeffe PhD, a research fellow and sleep physiologist at the Sleep/Wake Research Centre, Massey University.

Recommended resources

- The Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre website provides self-help information for patients about how to improve their sleep during their hospital stay: www.mskcc.org/cancer-care/patient-education/improving-your-sleep-during-your-hospital-stay.

- The Australasian Sleep Association has resources for health professionals on sleep disorders: www.sleep.org.au/professional-resources/health-professionals-information.

- The Sleep Health Foundation Australia has resources for patients and health professionals on sleep health and sleep disorders and their management:

www.sleephealthfoundation.org.au.

References:

- NIGHTINGALE F (1860). Notes on nursing. Appleton & Company. Accessed 7 April 2017 from http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/nightingale/nursing/nursing.html

- CRAFT J, GORDON C, HUETHER S, MCCANCE K, BRASHERS V, & ROTE N (2015). Understanding pathophysiology. Mosby: Sydney.

- SCHWARTZ JRL, & ROTH T (2008). Neurophysiology of sleep and wakefulness: Basic science and clinical implications. Neuropharmacology 6, 367-378.

- SILBER, MH (2012). Staging sleep. Sleep Medicine Clinics 7 (3) 487-496.

- SU C-P, LAI H-L, CHANG E-T, YIIN L-M, PERNG S-J, CHEN P-W (2012) A randomized controlled trial of the effects of listening to non-commercial music on quality of nocturnal sleep and relaxation indices in patients in medical intensive care unit. Journal of Advanced Nursing 69(6). doi: 10.111/j.1365-2648.2012.06130.x

- PULAK L, & JENSEN L (2016) Sleep in the intensive care unit: A review. Journal of Intensive Care Medicine 31(1) 14-23. Doi 10.1177/0885066614538749

- RADTKE K, OBERMANN K, & TEYMER L (2014). Nursing knowledge of physiological and psychological outcomes related to patient sleep deprivation in the acute care setting. MEDSURG Nursing 23(3) 178-184.

- RITMALA-CASTREN M, LAKANMAA R, VIRTANEN I, & LEINO-KILPI H (2014). Evaluating adult patients’ sleep: An integrative literature review in critical care. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 28, 435-448. doi: 10.1111/scs.12072

- MISSILDINE K, BERGSTROM N, MEININGER J, RICHARDS K, & FOREMAN M (2010). Sleep in hospitalised elders: A pilot study. Geriatric Nursing 31(4) 263-271.

- BARTICK M, THAI X, SCHMIDT T, ALTAYE A,

& SOLET J (2010). Decrease in as-needed sedative use by limiting night time sleep disruptions from hospital staff. Journal of Hospital Medicine 5(3) E20-E24. doi; 10.1002/jhm.549 - HELLSTRÖM A, FAGERSTRÖM C, & WILLMAN A (2011). Promoting sleep by nursing interventions in health care settings: A systematic review. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing 128-142. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2010.00203.x

H - OEY L, FULBROOK P, & DOUGLAS J (2014).

Sleep assessment of hospitalised patients: A literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies 51, 1281-1288 http://dx.doi.org/10.1061/j.ijnurstu.2014.02.001 - TROTTI LM (2016). Waking up is the hardest thing I do all day: Sleep inertia and sleep drunkenness. Sleep Medicine Reviews http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2016.08.005

- FILLARY J, CHAPLIN H, JONES G, THOMPSON A, HOLME A, & WILSON P (2015). Noise at night in hospital general wards: A mapping of the literature. British Journal of Nursing 24(10) 536-540.

- KAMDAR B, SHAH P, KING L, KHO M, ZHOU X, COLANTUONI E, COLLOP N, & NEEDHAM D (2012). Patient-nurse interrater reliability and agreement of the Richards-Campbell sleep questionnaire. American Journal of Critical Care 21(4) 261-269, doi: 10.4037/ajcc2012111

- NURSING COUNCIL OF NEW ZEALAND (2010, amended 2016) Competencies for registered nurses. Retrieved May 2017 from www.nursingcouncil.org.nz/Publications/Standards-and-guidelines-for-nurses.

The app was launched by the Asthma and Respiratory Foundation NZ and the information on signs, triggers and treatments includes links to downloadable documents and pages on the foundation’s website. It also provides users with a digital template they can work through with their nurse or doctor to develop an asthma action plan that matches the medication and treatment required for different peak flow levels and symptoms ranging from ‘feeling good’ to ‘severe’ or ‘emergency’. The app also links to an external website where users can take an asthma control test.

PROs include: Engaging and appealing design. Asthma action plan can be shared as an email attachment with family members and sport coaches etc.

CONs include: Only has generic, not real, images of commonly used inhalers. Doesn’t feature symptom tracking or reminder settings.

Full app review at www.healthnavigator.org.nz/app-library/m/my-asthma-app

The NZ App Project: Health Navigator, a non-profit trust, is using technical and clinical reviewers to help develop a New Zealand-based library of useful and relevant health apps. Health professionals who would like to be part of the project can email [email protected].

]]>But major health reforms underway means that hospitals like Shenzen People’s Hospital (SPH) now need to develop a more decentralised health service. In the absence of community healthcare facilities, one model adopted by SPH – the largest public hospital in the southern Chinese city of 20 million people – has been for hospital nurses to provide a follow-up discharge health service. By the end of 2016, a total of 1,590 patients from the 2,400-bed hospital had received home visits from their primary care nurses after being discharged.

Alternative models of delivering health care were among the topics discussed when last year some of SPH’s 1,174 registered nurses were hosted by Wintec during a series of one-week visits to learn more about the New Zealand healthcare system.

The thinking behind SPH’s model was that hospital nurses were more familiar with their patients’ health situation and therefore best positioned to provide both inpatient and outpatient care. In the neonatal unit, for example, neonatal nurses who had supported the parents and caregivers of premature babies (weighing less than 1,500 grams) would provide an extension of their hospital role during home visits, taking follow-up blood samples when needed and arranging other postnatal support.

However, a critical shortage of nurses in China is now looming because of a relaxation of the one-child policy, forcing SPH to revise the model. The visiting SPH nurses learnt that in New Zealand, rather than providing home visits by primary nurses from a hospital, the inpatient team, prior to discharge, arrange outpatient follow-up with the appropriate professionals, such as a GP, district nurse or nurse specialist. Discharge summaries accompany patients and relevant information – such as medication, diagnostic tests and follow-up needs – are shared with these primary health professionals.

In addition, the SPH nurses, during discussions about the differing healthcare systems and sociocultural contexts in which nurses in China and New Zealand practise, recognised that primary healthcare provision in New Zealand was not defined solely by the provision of medical care. And that while treating illnesses and monitoring a patient’s programme of recovery is important, comprehensive community health care focuses on education and empowerment so that people are aware of the influences affecting their health and have more personal choice accordingly. In other words, comprehensive community health care not only addresses medical concerns but also examines other issues that stem from a person’s broader social landscape.

For the Chinese, it can be foreseen that the New Zealand model might better suit the needs of their nation in order to promote a balanced system of health promotion, disease prevention, rehabilitation and illness treatment.

Separating inpatient care from follow-up outpatient care would doubtless also take the pressure off hospital nurses. Perhaps it is time for the development of off-site community healthcare hubs, where multidisciplinary teams of general practitioners, social workers, physiotherapists, occupational therapists and other healthcare professionals work together to address the social, political and environmental factors that impact on people’s health.

]]>After nearly 25 years working in primary health – a journey that has taken her from practice nurse to chief operating officer of one of the country’s four biggest primary health organisations – Kerr knows she has some catching up to do on secondary care nursing.

She is also aware that a DHB appointing a director with such a strong primary health background may be “quite unique”, but suspects she was successful because as a leader she is “very pragmatic, systems-oriented and clinically sound”.

With integrated services high on the health policy agenda, her background in primary health can be seen as a strength for a nursing leadership role covering nurses across the health sector – and not just in secondary care.

And she says what she doesn’t know about hospital systems and hospital nursing she is ready to learn.

Kerr’s career to date certainly shows a willingness to learn. In 2000 the practice nurse leader was tapped on the shoulder to join Hora Te Pai Health Services, a new iwi provider on the Kapiti Coast.

She started out as the nurse and manager of two community workers, an admin person and a voluntary, part-time GP.

By the time she left nearly a decade later, the staff numbers had swelled to 17.

Her latest role has been chief operating officer for Compass Health, the primary health organisation serving the greater Wellington and Wairarapa regions. Compass Health provides not only general practice services but also a range of wider, mostly nurse-led, community health services, including school-based services, outreach nursing and mental health, which Kerr managed along with integrated care development.

Kerr trained at Wellington Hospital between 1980 and 1983 and nursed in women’s health until 1989, rising to acting charge nurse before taking maternity leave.

She returned to nurse part-time in residential aged care nursing and then in an older people’s health ward, before beginning practice nursing in 1993. Along the way she also gained her postgraduate diploma in primary health.

By 2000, when she was asked to become Hora Te Pai’s first registered nurse and manager, she was already a practice nurse leader, having helped to set up a new practice and mentoring nurses new to primary health.

So when in 2001 the Wellington Independent Practitioners Association (WIPA) came to talk to the iwi provider about the move to primary health organisations (PHOs) and becoming part of the new Kapiti PHO, Kerr was ready to take a leadership role.

She quickly became a member of the PHO’s establishing committee, then the board, and then became its chair from 2006 to 2009, only resigning to become clinical director at Compass, which ultimately absorbed Kapiti PHO in 2010.

Kerr believes she gravitated quite naturally to leadership roles. “My passion and my drive is really to make a difference to people, so when these opportunities come up I haven’t held back,” she says. “But I will always see myself as a nurse first and foremost, no matter what I do.”

She acknowledges the main learning curve in the new role she started on 31 July is gaining a better understanding of the nursing workforce she leads and how the hospital works. “Finding out things like are there enough nurses at the right level and the right skill mix and the right training to be able to do what is required? Do they need nurse prescribers? What is the place of nurse practitioners within wards?”

She also plans to bring her primary health experience to the fore to improve the integration of care and how the DHB can empower nurses in the community to do more, including supporting primary health nurses to work at the top of their scope.

It sounds a heady time, but it’s one that Kerr is enjoying. She says her family keeps her balanced – as does a love of trail running/hillwalking (she has set herself a target of completing 21 21-kilometre races).

“It’s about just getting out in nature where you can offload, clear your mind and get rid of some of the clutter,” she laughs.

]]>When PhD researcher Margaret Hughes interviewed registered nurses and enrolled nurses about direction and delegation roles, she found “utter confusion”. But that confusion only becomes visible, she says, if a delegation of patient care goes “horribly wrong”.

Hughes’ qualitative research involved indepth interviews with 36 nurses – 17 registered nurses and 19 enrolled nurses – across a range of settings and from the inexperienced to the very experienced. She concluded that gaps in the Nursing Council’s direction and delegation guidelines need to be filled and aspects of the delegation process should be made more overt.

“The strength of the guidelines is that they are broad, but that is also their downside,” says Hughes. “And very few nurses actually read them as they don’t provide the practical help nurses are seeking.” She says all the nurses she spoke to wanted more training and support from their leaders on how to direct and delegate.

Hughes says the current workforce includes a generation of registered nurses (RNs) who rarely worked with enrolled nurses (ENs). So the arrival on wards and other healthcare settings of a new cohort of ENs – plus health care assistants (HCAs) with variable skillsets and qualifications – exposes skill gaps in direction and delegation. As one RN she interviewed put it: “We are just supposed to know this stuff by osmosis.”

Hughes says her findings highlight not only the confusion around the different roles in the direction and delegation relationship, but also the need to overtly state that ENs (and likewise HCAs) have the right and responsibility to self-assess and decline a delegated nursing task if they believe they can’t do it safely.

The confusion could be reduced, believes Hughes, by leaders and managers providing workplace-relevant information and training on how to carry out ‘good’ direction and delegation. Some of her suggestions for useful additions to the nursing tool box in this area include looking at communication strategies, how to quickly assess or self-assess an EN’s or HCA’s skills, and providing clear, workplace-relevant guidelines on who is responsible for what. (See also related article ‘Utter confusion’ and the PD article and learning activity Providing nursing direction and delegation with confidence, wisdom, and respect.)

Not just an allocation of tasks: good communication needed

Respectful communication is essential for developing a good direction and delegation relationship, says Hughes.

A harried nurse standing hands on hips in the corridor telling an EN or HCA to “go do this” or “go do that” is neither good communication nor a respectful relationship.

Hughes’ research shows that for delegation to be successful it needs to be a relationship rather than just one person issuing a set of instructions to another. And communicating professionally and well is crucial, otherwise the relationship can break down and patient safety suffers as a result.

Providing staff with training in respectful and inclusive communication styles and strategies is therefore important, says Hughes – including the basics such as what tone to use, and avoiding body language like hands on hips.

“I know nurses are busy; you are tired and you are running, but if you don’t get the communication right you have a communication breakdown and that puts the patient at risk.”

Speedy assessments required

In a busy ward the delegation of patient care can by necessity happen very quickly.

A lot needs to happen in that short time including, according to the Nursing Council guidelines, the RN assessing “the health status of the health consumer, the complexity of the nursing intervention required, the context of care, and the level of knowledge, skill and experience of the enrolled nurse”. At the same time, though not stated, the EN (or HCA) needs to self-assess whether they currently have the skill and experience to do the task or tasks asked of them.

Hughes says during her interviews it became clear that nurses want guidance from their leaders and inservice education on performing this quick but very important assessment role.

If the RN and EN (or HCA) has a longstanding working relationship, this assessment may be relatively simple. But when staff are new, inexperienced or – as increasingly happens under the Care Capacity Demand Management system – have been sent to help out in an unfamiliar ward or service, they may have to start that relationship from scratch.

Hughes says the first rule is to ask and not assume anything, which sounds obvious, but her research showed it wasn’t happening. “Just because the enrolled nurse looks older – don’t assume they are experienced, as they may have just graduated.”

Likewise, because an EN or HCA is able to perform a task in a surgical setting, don’t assume they are skilled enough to do it in a spinal unit or mental health service.

RNs also need to make sure they are asking in an environment where the EN or HCA doesn’t feel too intimidated to say, “I’m really sorry but I can’t do that”.

“But I’ve come across examples of RNs putting their hands on their hips and asking (in a scathing tone) ‘so what can you do?’” says Hughes. “And if an EN or HCA doesn’t feel safe to say they aren’t skilled enough for a certain task then that impacts on patient safety.”

Of course, says Hughes, an EN or HCA can’t just continue to say “I can’t do this” as it will eventually become an employment issue. But there is also an onus on the clinical nurse management team to provide training opportunities so an EN or HCA can upskill, as well as provide clear role descriptions for staff, based on their scopes. In addition, employers are responsible for ensuring the right skill mix to provide safe patient care and for ensuring that RNs are supported and sufficiently competent to safely delegate care and that ENs and HCAs understand their delegated roles and responsibilities.

Dedicated training and planning tools could be useful

Developing an e-learning tool dedicated to training nurses in the knowledge and skills needed for direction and delegation would be very useful, believes Hughes.

Similar training programmes have already been developed in district health boards around the country to teach the handover or communication tool ISBAR (introduction/identify, situation, background, assessment, request/recommendation – also known as SBARR or SBAR).

She says such a tool needs to go beyond the current delegation guidelines and should cover areas like handy hints on collaborative communication, guidance on how to assess and self-assess skills, and making clear the responsibilities of each party to a delegation relationship.

These include making clear that an RN is not responsible for the nursing practice of the enrolled nurse (or an HCA’s actions) but is responsible for the way that direction and delegation is initiated and the patient’s overall plan of care. Similarly, the EN or HCA is responsible for self-assessing and declining a task that they don’t have the skill or experience to undertake safely.

Depending on the model of care, the development of suitable planning tools could also be useful. Hughes says she spoke with one RN who had experienced a planning tool used in an Australian hospital where the RN and EN worked through a patient’s care plan together to decide who was best suited to perform each listed task, and then ticked them off as they were completed.

Hughes acknowledges that having good direction and delegation all takes time and, while the Nursing Council recommends employers factor time into a nurse’s workload to safely delegate care, this doesn’t always happen.

“The RN has got to slow down and take the time to quickly – in seconds – assess the EN (and find a replacement if the EN is not able to do it). And also take the time to make sure that the tone, and what, and how she is saying things is collaborative. Also time for the EN to self-assess, do the job, and report back to the RN. All of this takes time.”

Hughes says you could argue that expecting nurses to find the time to do delegation properly is just “pie in the sky”.

“But actually there were two patient deaths just in the course of this research and many, many examples of lack of patient dignity, like patients wetting beds as their bells weren’t answered,” says Hughes. “That is not acceptable and it goes totally against the Bill of Rights.”

All nurses she spoke to want to do it better to ensure they keep their patients safe.

“It’s the how to do it that they are asking for.”

Recommendations for nurse leaders to improve direction and delegation skills

- Enrolled nurses (and healthcare assistants) must be given time to quickly self-assess and decline a task they are not confident to do.

- Workplace leaders supply information and training to support ‘good’ direction and delegation interactions including on assessment roles, communication styles and who is responsible for what in the interaction.

Recommendations for updating Nursing Council guidelines

- The guidelines should make clear that an EN has both the right and the professional responsibility to self-assess and decline a delegated task.

- That there should be separate guidelines for registered nurses and enrolled nurses that make clear who is accountable for what in the delegation relationship and include guidance on good communication strategies.

The “bit of a disaster” was a fire in the wee hours of that morning in Lakes DHB’s main computer server room in the Rotorua Hospital site. The fire had started in the, somewhat ironically named, uninterruptable power supply (UPS) that had more than interrupted the DHB’s IT system – all electronic services served by that main computer server were out of action, leaving the Rotorua and Taupo hospital sites and community service teams without access to electronic patient management systems, the internet, email or even voicemail.

As a result, everybody was about to start the new week with blank screens.

Lees says everyone in the DHB’s executive team is trained to operate within the CIMS (coordinated incident management system) structure but he has a special interest and had just recently completed a postgraduate diploma in emergency management at AUT. So when it was agreed that a formal emergency operation centre was needed, the DHB’s director of nursing and midwifery volunteered to become incident controller, set up an emergency control centre and called the first of the three-hourly incident meetings for 9am.

The situation was fairly grim. How long it would take to get ‘all systems a go’ again was a big unknown. Meanwhile two hospitals had to continue safely.

“We couldn’t get anything to come up on any computer screen anywhere in the system,” says Lee. People could phone each other, but couldn’t leave voicemail messages, and there was no intranet or access to the electronic management systems that staff now took for granted. In all, 54 software products used by DHB clinical and administration staff were unavailable, including electronic meal ordering.

Lees says that on the good news front the laboratory was on a different computer system so blood reports were still available and also radiology could still do scans and imaging so those diagnostic tools weren’t affected.

The problem was how to share results and information that people were now accustomed to receiving and storing electronically.

The DHB’s business continuity plan meant it already had on-hand templates for paper versions of all the electronic forms commonly used by the DHB.

The team quickly got a laptop and printer to work printing off templates; IT staff were sent running about the hospital to set up ward printers to be used as photocopiers, and the communications officer was set up to be able to write and print staff bulletin updates. Lees says by about 10am the hospital had switched into paper mode and was tracking admissions and discharges on paper, as well as taking meal orders.

To get paper from A to B and back again – and keep staff updated – the incident team ramped up the existing internal post system by bringing in more runners, including nurses in roles such as nurse educators, who could be pulled out of their normal duties to help out during the IT crisis.

Fortunately the DHB’s patient records were not fully digitised, so it had paper files containing paper copies of most, if not all, the patient information and reports held electronically up to the time of the outage.

Lees says it was also lucky that the medical records office was in the habit on Friday afternoons of printing off the electronic theatre and outpatients list for the first days of the following week, so the DHB had paper lists of who was due to present and made the clinical decision to postpone some surgery and appointments until the impact of the outage was clearer.

The emergency department was a clinical priority so it was loaned the incident control team’s stand-alone wifi hotspot, which can connect up to six laptops or tablets, so that it could access national systems to check or create NHI (National Health Index) numbers.

Also supporting ED was the “absolutely brilliant” primary health organisation, Rotorua Area Primary Health Services, which turned up at ED with some of its own computer equipment, allowing ED staff to regain their usual access to GP patient records, but directly via the PHO’s network.

The DHB’s pharmacy found its own quick fix by logging in to Taranaki DHB’s ePharmacy system using a mobile phone, the 4G network and a laptop, so it was quickly back dispensing medicines as normal. Lees says that staff in other areas popped home and got their laptops and printers. He expects a number also used personal mobile data and devices to access clinical apps or support systems – improvisation was the order of the day.

Getting back on track

Day one had started with some clinical concern and uncertainty about attempting business as usual in the midst of an IT outage, says Lees. But by midday people were “much happier”.

By the end of that first day the two hospitals were functioning, slowly and with some inconvenience – and with some inevitable concern about missing something stored electronically – but overall Lees said there was an “amazing response” by everyone. “We were so, so pleased with how the nurses, allied health, doctors, support staff and admin people all pulled together.”

By Tuesday, surgery and outpatients were basically back to normal and the hospital’s free public wifi system, provided by an external company, was up and running. It wasn’t secure so it couldn’t be used for transferring patient data, but it did give staff with mobile devices and laptops free access to the internet, and the DHB’s external website could be used to share outage updates.

While the emergency control centre worked on keeping the hospital up and running under a paper-only regime, the specialist IT team was swiftly seeking expert advice on how best to get the IT system’s backup running.

The DHB had to track down and fly in forensic cleaning experts to clean up the smoke and soot in the server room and it had to find, hire and install a replacement UPS. This meant IT staff working round the clock, and neighbouring DHBs lent IT and emergency planning staff to share

the load.

The first time the switch was flipped on the replacement UPS, the air-conditioning failed and the DHB had to wait another 24 hours to get replacement parts to ensure that the room had the consistent temperature and humidity control required by the sensitive server equipment. The IT team also started working on setting up a backup secondary server to run a skeleton IT system and was on standby to redeploy 50 desktop computers or laptops – to replace computer monitors that couldn’t run without the main server – to every ward or outpatient clinic room to run the patient management system.

Fortunately, when the switch was flipped again on the Wednesday night, the full system came back to life.

With the health system nationwide moving steadily towards full electronic health records, the Lakes outage has highlighted the vulnerability of a health service being reliant on a single server site.

Having a backup server offsite in theory sounds a good idea, but Lee says he was told that there was about $2 million of IT ‘kit’ in the server room so duplicating that wasn’t an option for small DHBs. And also it wasn’t the server itself that failed – all data was safely backed up and not at risk of being lost – it was the loss of a guaranteed uninterrupted power supply to the server that was the major issue. (Not taking the risk of plugging the server straight into mains power was brought home that week by a storm cutting power to Rotorua homes and creating a power spike big enough to have blown everything in the server room.)

The July IT outage has prompted Lakes to speed up joining the regional data centre being developed in Hamilton for the Midland region DHBs. This is part of the national infrastructure platform that aims to increase the security and reliability of DHBs’ IT infrastructure and reduce the risk of critical outages.

“Business as usual”

Everyone involved was relieved that the outage lasted just three inconvenient and challenging paper-shuffling days.

Returning to “business as normal” turned out to be, however, not just a matter of successfully flipping the switch.

Electronic patient management systems were up and running on the Thursday, but patients who had been admitted on paper couldn’t be discharged electronically until somebody manually uploaded the information from the paper admission forms. This meant that paper discharges had to continue until the hospital caught up with inputting the backlog of paper forms.

Hiccups emerged when staff inputting the forms discovered gaps in the information – that electronic templates would normally prompt nursing or clerical staff to complete – and these gaps were time-consuming to fill once the patient was long gone home.

This has prompted another lesson learnt for Lees, who says if ever Lakes had to revert to paper forms again it would set up a small team to check over filled-in forms immediately and send them straight back if gaps were spotted.

Lees and the incident control team finally handed over to a recovery manager at 2.30pm on the Thursday after an intense and challenging three and a half days.

Time to take a deep breath… and catch up on all those emails that spilled into his mailbox after Lakes rejoined the digital world.

Advice and lessons learned

- Have a business continuity plan – even if the reality is different, having worked through different ways of responding to emergencies is invaluable.

- Use a CIMS (Coordinated Incident Management System) approach right from the beginning of a major incident – don’t think you can manage it with your normal processes.

- Set up a system so you can save and still access electronic surgery and outpatient client lists if an outage occurs.

- Keep paper templates of electronic forms up to date and consider having a stockpile of pre-printed paper forms.

- Consider knowing how many standalone desktop computers and laptops you can deploy i.e. that aren’t reliant on the main server to operate.

- Have more than one stand-alone wifi hotspot device on-hand for emergencies.

- Move the UPS (uninterrupted power supply) outside of the server room to remove the risk of a fire in the UPS damaging the server.

- Big picture – pursue shifting to regional IT data and infrastructure models sooner rather than later to increase security and reduce the risk of critical local outages disrupting electronic services.

Registered nurses worry they’ll get into trouble if the person to whom they delegate a nursing activity ‘mucks up’. Enrolled nurses (or healthcare assistants) worry what will happen if they turn down a task they think is outside their skill set.

Looking at the Nursing Council’s Guideline: responsibilities for direction and delegation of care to enrolled nurses is a useful starting point for discussing what is actually required for good direction and delegation. And who is responsible for what.

The 2011 guidelines are by necessity broad-brush as they cover both registered and enrolled nurses’ responsibilities across the diversity of nursing workplaces. (Similar guidelines were also released in 2011 for delegating to unregulated health care assistants (HCAs). The guidelines provide definitions (see box) of direction, delegation and accountability, and list a number of responsibilities required of both registered and enrolled nurses (RNs and ENs), and employers during delegation.

Accountability is clearly defined in the guidelines as “being answerable for your decisions and actions”. In the guidelines, and also in the enrolled nurse scope of practice, it states that the enrolled nurse is “accountable for their own nursing practice”. (Likewise the Nursing Council’s HCA delegations make clear the HCA is accountable for their own actions.) But despite no guideline or nursing document in New Zealand stating that an RN is responsible for a delegated EN’s nursing practice, many RNs continue to believe that they are.

At the same time, the enrolled nurses’ scope states that the RN maintains responsibility for the overall “plan of care”. But there is a lack of recognition that RNs are responsible for the way that direction and delegation is initiated and managed (as direction or delegation may be part of the overall “plan of care”).

This can create confusion for nurses who are told in their respective scopes of practice that they are required to direct or delegate, or be directed or delegated to, but are unsure how exactly to carry out this role.

This is especially true for new, inexperienced RNs who are required to delegate to highly experienced ENs, casual and agency RNs unfamiliar with the specialised ward they have been sent to, and new inexperienced ENs emerging on to the employment scene in greater numbers expecting to be directed, or delegated to.

Some of the direction and delegation assessments required of the RN include the need to “assess the health status of the health consumer, the complexity of the nursing intervention required, the context of care, and the level of knowledge, skill and experience of the enrolled nurse” (Nursing Council of New Zealand, 2011, p. 8). However, the EN’s role during these assessments is not covered in the guidelines.

The story in the following sidebar is a true account of an experienced EN who is sent to an unfamiliar ward due to overstaffing in her own workplace. The story illustrates what can happen when the art of delegation goes wrong because the skills and attributes required for ‘good’ delegation are not known (or used). So instead, delegation just becomes an allocation of tasks. (See also related article: Direction and Delegation: when it goes wrong and the PD article and learning activity Providing nursing direction and delegation with confidence, wisdom, and respect.)

The art of assessment

The advanced communication and, more importantly, listening skills required by registered nurses to assess the knowledge and skills of an enrolled nurse (or HCA) they are delegating to are part of the art of ‘good’ delegation, along with the ability of the enrolled nurse (or HCA) to self-assess their own competence to take on a delegated activity or task.

Deanna’s story (see sidebar) shows that an essential element for ‘good’ delegation practice is registered nurses understanding that enrolled nurses are responsible for self-assessing their own knowledge and skills and for saying ‘no’ if they are unsure of the delegated task or do not feel comfortable or safe to carry it out. A poor understanding of the rights and responsibilities of delegation can lead to confusion and poor outcomes for the nurses involved.

However, how an RN should carry out this professional competency – in particular the swift assessments required before delegating and directing a nursing task – are not included in any guidelines on direction or delegation in New Zealand. Nor are the advanced self-assessment skills required of the ENs. When registered nurses do not understand these roles and do not make the required assessments before delegating, there can be negative consequences for the patient, such as the EN carrying out unfamiliar and therefore unsafe tasks.

There is also an ambiguity related to lines of accountability in the guidelines, and there is no advice or discussion about the RN’s role in leading the direction or delegation interaction. The impact of a lack of leadership, and confusion about the direction and delegation role, are magnified when there is poor communication.

Poor communication and confusion about roles and responsibilities can lead to a reluctance to be directed or delegated to, or to direct or delegate. A lack of direction or delegation interactions means that both registered and enrolled nurses could be working outside their scopes of practice.

Summary

The art of direction and delegation is a delicate balancing act between ensuring a thorough set of assessments are carried out, leadership of the delegation interaction is provided, and that there is good communication. These skills and abilities are required in busy nursing workplaces where there are many decisions needed.

The consequences of getting it wrong can impact negatively on the patient on the receiving end of the direction or delegation decision – and on a nurse’s registration.

To master the art of direction and delegation, nurses need time to carry out assessments, to learn about direction and delegation, and time for their leaders to support their access to direction and delegation information and advice.

AUTHOR: Margaret Hughes explored registered and enrolled nurses’ direction and delegation communication practices in New Zealand for her PhD thesis (see p. 26). She is a senior lecturer at Ara Institute of Canterbury’s school of nursing.

Direction or delegation?

Direction is the active process of guiding, monitoring and evaluating the nursing activities performed by another. Direction can be provided directly or indirectly.

Delegation is the transfer of responsibility for the performance of an activity from oneperson to another, with the former retaining accountability for the outcome.

Recommendations

- Separate guidelines for registered and enrolled nurses that clearly explain who is accountable and for what (including the registered nurses’ role in leading the delegation interaction).

- Guidelines make clear that an enrolled nurse has the right and the professional responsibility to self-assess and decline to do a delegated task.

- Guidelines include advice on inclusive and respectful communication strategies required by registered and enrolled nurses during the direction and delegation relationship.

- Workplace-specific information about direction and delegation roles and responsibilities would be a useful addition to the nursing tool box (see related story in Leadership & Management on p. 26).

Deanna’s story – a true account

Deanna* had been transferred to an unfamiliar ward because the ward was short of staff. Being shifted between wards had happened many times in her 40-year nursing career, but this shift turned about to be slightly different. The lack of welcoming to the ward and the lack of consultation about the tasks Deanna was ‘instructed’ to do were the start of an unpleasant and anxious time for her.

On arrival the RNs told her they had really wanted an “IVed” registered nurse, “not an enrolled nurse!” They then assigned her a set of tasks to carry out saying that “at least you can be another pair of hands”. Deanna explained that she did not feel confident doing the tasks they were asking of her as she had not worked in this specialty nursing workplace before. The delegating RN became angry and accused her of “being difficult”.

That evening the RNs got together to write a formal complaint about her poor performance. The charge nurse of the ward in question – new to her position and unfamiliar with delegation – had not supported Deanna’s right to self-assess and to decline to do the delegated tasks. The complaint from the RNs about her was upheld and there were further meetings and repercussions that “really knocked her confidence”.

The avoidable and unpleasant situation was hard for her to come back from and made her question if she wanted to continue in nursing. Deanna knew and understood that she had a responsibility to say ‘no’ if she felt that the task being asked of her was outside her skill level, training and confidence, but the charge nurse and the registered nurses who had written the complaint, did not.

It wasn’t until many weeks later that she realised how the lack of being welcomed on to the ward, and being referred to as “another pair of hands” had devalued and affected her. Deanna explained that she had worked with many RNs who had shared their knowledge with her and supported her to be a contributing member of the team. “We’re not just here for ourselves you know. We’re here to help others, so anything or anyone who helps me do this is respected by me.”

She believed that ENs needed to be assertive and know how to politely and diplomatically say ‘no’ to a delegated task when required so that they did not take on tasks that were unsafe for the EN, and therefore the patient. However, there needed to be a respectful and inclusive communication approach from RNs too.

*Not her real name

]]>Children in the community with signs of mildly infected eczema respond well to topical emollient and corticosteroids. Adding oral or topical antibiotics appears to have little clinical benefit.

Clinical scenario

As a nurse, you notice some children’s symptoms improve with just the usual topical emollients and corticosteroids. You decide to review the evidence on the effectiveness of antibiotics for treating mildly infected eczema.

Question

In children with signs of infected eczema, do antibiotics, in addition to topical emollient and corticosteroids, improve symptoms?

Search strategy

PubMed Clinical Queries (therapy, narrow): eczema AND antibiotics

Citation

Francis NA et al. (2017). Oral and Topical Antibiotics for Clinically Infected Eczema in Children: A Pragmatic Randomized Controlled Trial in Ambulatory Care. Ann Fam Med, 15(2), 124-130. doi: 10.1370/afm.2038

Study summary

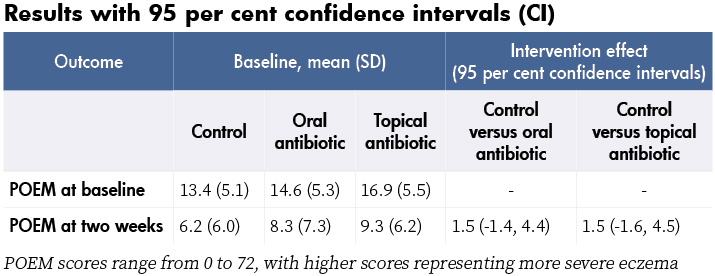

The CREAM (Children with Eczema Antibiotic Management) study was a three-arm, double-dummy, blinded, randomised controlled UK trial involving children with atopic eczema presenting with clinically suspected infected eczema. Included were children (mean age was 3.1 years) with signs of infected eczema that could include: failing to respond to standard treatment with emollients and/or mild-to-moderate topical corticosteroids; a flare in the severity or extent of the eczema; weeping or crusting. Excluded were those who had recently used potent topical corticosteroids or antibiotics, had features of severe infection, or significant comorbidities. Of 171 children assessed, 113 were randomised to one of three study arms.

Standard care: Topical corticosteroid: hydrocortisone one per cent for the face and clobetasone butyrate 0.05 per cent (or equivalent) for other parts of the body, and an emollient of parents’ choice (non-antimicrobial). Follow-up at two weeks, four weeks by research nurse and at three months via clinical record review.

Intervention 1: (n=36) Oral antibiotic and topical placebo (oral antibiotic group): flucloxacillin (floxacillin) suspension (250mg/5mL), or erythromycin suspension (250mg/5mL) for those with penicillin allergy, for seven days using age-adjusted doses.

Intervention 2: (n =37) Topical antibiotic and oral placebo (topical antibiotic group): two per cent fusidic acid cream, applied three times a day for seven days.

Control: (n= 40) Oral and topical placebos (control group): Placebos were matched by taste and appearance.

Primary outcomes: Eczema severity (skin redness, cracking, soreness, itch, sleep disturbance, oozing or weeping, bleeding, and fever) at two weeks measured by the patient-oriented eczema measure (POEM).

Secondary outcomes: Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), Infants Dermatitis Quality of Life instrument or Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (depending on age of child); Dermatitis Family Impact (DFI)18 instrument, and the Atopic Dermatitis Quality of Life instrument; adverse events.

Study validity

Randomisation – yes; allocation concealment – yes (information from protocol); complete follow-up – small loss to follow-up for primary outcome; intention-to-treat analysis – all participants with baseline and two-week POEM scores were included; blinding – yes, children, parents, outcome assessors; equal treatment between groups – appears so; groups similar at baseline – yes, including POEM scores, infection features, and skin swab S. Aureus results. Overall, a high-quality study.

Results

At baseline, 104 children (93 per cent) had one or more of the following: weeping, crusting, pustules, or painful skin. Also 70 per cent had S. aureus isolated from a skin swab and 27 per cent of those were resistant to fusidic acid. At two weeks, POEM scores had reduced (improved) in all three groups, with no significant differences in the POEM scores of the two intervention groups compared with control (see table). No significant differences in POEM scores were found at four weeks and three months either, or in secondary outcomes or adverse events. No serious adverse events were reported.

Comments

- Children recovered quickly, regardless of treatment group.

- Topical corticosteroids use was measured and similar in each group. Adherence to oral and topical antibiotic (or matched placebos) was 61.3 per cent and 81.8 per cent respectively. Adjusting for adherence differences did not change the results.

- Although recruitment targets were not met, the lower boundaries of the confidence intervals (-1.4 and -1.6) are less than an effect from treatment considered to be important to patients (published minimal clinically important difference for POEM is three), suggesting that a larger study would not change these results.

- Results do not apply to children with severe infection.

Reviewer: Cynthia Wensley RN, MHSc. Honorary Professional Teaching Fellow, University of Auckland and PhD Candidate, Deakin University, Melbourne. [email protected]

]]>

This 1909 statement from Hester Maclean, our country’s first chief nurse, could probably take pride of place as Exhibit A when arguing the case that a nurse’s monetary worth has historically been undervalued because of the association with ‘womanly’ qualities.

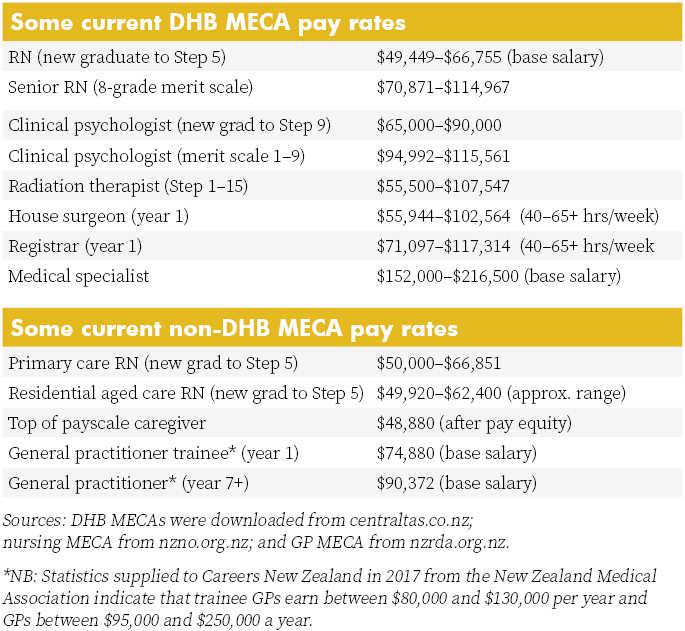

Such evidence might be needed after the NZNO lodged a pay equity claim in June for nurses working in DHBs as part of its bargaining talks. Pay equity claims are said to have merit if the work is performed predominantly by women; there are ‘reasonable grounds’ to believe the work has been historically undervalued because it uses skills or qualities ‘generally associated with women’; and the work continues to be subject to gender-based undervaluation.

Nobody is expecting such a claim to be settled quickly, particularly as the shockwaves from the historic pay equity settlement for caregivers are still being worked through, particularly by nurses in the residential aged care sector who have lost pay relativity with their unregulated co-workers (see story last edition).

But NZNO sees the pay equity claim as the first page in the final chapter of closing the gender pay cap for its DHB nurses (and other members) and, eventually, nurses beyond the public health sector.

The union argues that, unlike the 2005 Fair Pay settlement, this time around the Kristine Bartlett vs TerraNova pay equity settlement is creating not only a legal precedent but also a legislative framework to pursue and settle pay equity claims (although unions are not happy with the current wording of the draft bill introducing that framework).

It is also acknowledged that the pay equity process will take time, with NZNO industrial services manager Cee Payne writing in Kai Tiaki recently that eliminating the gender pay gap would “most likely take the next decade to be fully realised”.

“Not for the sake of money-making”

Our formidable first matron-in-chief and chief nurse Hester Maclean’s belief that nurses should put caring before commerce set the culture for much of the first half of the 20th century.

Nursing shortages in World War II saw a revised salary scale negotiated and a salaries advisory committee for public hospitals set up in 1947, but as the country settled back into peacetime nurses lost industrial traction, with little salary movement for nearly two decades. Nursing was once again seen as a feminine vocation not to be marred by talk of money.

In 1957 the New Zealand Nurses Association (the forerunner of today’s NZNO) even withdrew from the Council for Equal Pay and Opportunity for fear that the professional organisation might become “too political”.

But times were changing and in 1962 international advice was sought by the association on better methods for negotiating pay and conditions, leading in 1965 to the introduction of overtime and weekend penal rates – the first real pay rise since 1950 – and the replacement of the salaries advisory committee with an arbitration mechanism in 1969.

The 1970s saw public hospital nursing unionised, but it wasn’t until 1985 with the ‘Nurses are worth more’ campaign that nurses really tried to use industrial clout and public opinion to seek fairer pay, including marching on parliament for the first time. In an even bigger first, in 1989 nurses took strike action for the first time, followed soon after by a decade of health restructuring and industrial reform that saw nursing go into survival mode for much of the 1990s.

Pay jolt and pay gaps between sectors

With the new millennium and the return of national bargaining, nurses were again ready to look at the issue of pay equity. On Suffrage Day 2003, NZNO launched its ‘Fair pay – because we’re worth it’ campaign to gain pay parity for DHB nurses with teachers and police. After a hard-won campaign to get such a deal funded, a settlement was reached, leading to ratification in early 2005 of a national DHB multi-employer collective agreement (MECA) that introduced an up to 20 per cent pay jolt for nurses.

That pay jolt created a gap between DHB nurses and many of their non-DHB nursing colleagues. A decade later, that pay gap is nearly closed for nurses covered by MECAs in sectors such as primary health, family planning and prisons.

But the pay gap still remains for nurses with less industrial clout, including nurses in residential aged care, whose take-home pay is on average 23 per cent lower than their colleagues in public hospitals. And some nurses working for Māori and iwi providers are earning up to 20 per cent less than colleagues working for similar primary healthcare services. Those pay gaps are thrown into even starker relief by the realisation that the caregiver pay equity settlement could see the pay gap between nurses in those sectors and their unregulated colleague shrink or even disappear.

NZNO believes that the best step toward pay equity for all nurses is to begin by negotiating in the DHB sector, where it has the greatest numbers and influence. The State Services Commission and Combined Trade Unions (CTU) had also agreed that unions in the public sector could lodge pay equity claims through collective bargaining using the principles agreed by the tripartite Joint Working Group on Pay Equity late last year.

This led to NZNO lodging its claim when talks began in June, rather than waiting for the progress of the draft Employment (Pay Equity and Equal Pay) Bill, which NZNO and other unions oppose in its current form, saying it takes a backward step by placing new and “unreasonably onerous” requirements on women taking claims.

Meanwhile, once NZNO and the DHBs agree on terms of reference for pay equity talks, the task of assessing, with a gender-neutral eye, the value of nursing work in terms of skill, knowledge, responsibility, effort and working conditions will begin. Then comes selecting historically male-dominated occupations of equal value as comparators to back the claim that nurses are underpaid because of historic and ongoing gender inequity.

Hester Maclean might not approve, but it is probably about time that the value of a nurse “working for the good of her [his] fellow creatures” was calculated once and for all.

Lessons learnt from midwives’ pay equity case?

Community midwives lodged an historic pay equity claim under the Bill of Rights Act in 2015 and found that proving gender inequity was far from simple.

The College of Midwives’ claim for its self-employed lead maternity carers (LMC) led to mediation in 2016 with funder the Ministry of Health. In May this year it withdrew its court action after winning an interim pay increase and a legally binding agreement from the ministry that midwives would work with officials to design a new funding model for midwifery-led care that resolved the college’s longstanding concerns about pay equity and working conditions.

But in a report to members, the college said that after putting thousands of hours and dollars into researching and providing more than 3,000 documents for the case, it had proven easier to prove that midwifery pay was inequitable than it was to legally prove that inequity was due to gender.

LMC midwives had fought a case for equal pay for work of equal value in 1993 through the Maternity Benefits Tribunal and won, but there had been only two small increases since 2007, raising questions as to whether midwifery funding provided a sustainable income for the 24-hour, on-call service.

The midwifery case was unique because, as self-employed health professionals, community midwives were not covered by the Employment or Pay Equity Acts. But they too went through the process of looking at the historic discrimination of a female-dominated ‘caring profession’ and seeking out comparators in historically male-dominated professions. So are there lessons to share?

Alison Eddy, a midwifery advisor for the College of Midwives, says proving that a profession’s pay is inequitable because of gender is potentially difficult. She says it is easier to measure the clinical and technical skills and the professional accountability required of nurses and midwives than the so-called ‘soft skills’ that are also key to both female-dominated professions. The skills such as building relationships, working alongside people, and empowerment are all areas that can potentially be undervalued.

Commodifying those skills in order to match and compare pay with a comparator occupation in a field that has been historically male-dominated can also be challenging. Eddy says that after going through a lengthy process of using equitable job evaluation tools, the midwifery case had opted for pharmacists and GPs as two potential comparators and decided that midwifery fitted somewhere above the role of pharmacist and slightly below the role of GP.

Under the agreement with the ministry was the commissioning of an independent evaluation of the midwifery role and the provision of comparators and a market value for the role, using a gender-neutral lens, in readiness for a new funding model being in place by July 2018.

However, Eddy says that there are real concerns that the numbers now leaving the midwifery workforce due to feeling undervalued could impact on the sustainability of the service.

]]>