Reading this article and undertaking the learning activity is equivalent to 60 minutes of professional development.

This learning activity is relevant to the Nursing Council competencies 1.1, 1.4, 2.1, 2.8, 2.9, 4.1, 4.2 and 4.3.

Learning outcomes

- define catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI)

- describe the pathogenesis of CAUTI

- identify risk-factors associated with CAUTI

- identify CAUTI prevention strategies that nurses can implement to promote patient safety.

Introduction

Introduction

Catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI) is the most common healthcare-associated infection (HAI) worldwide1. Urinary tract infections (UTI) comprise 40 per cent of HAIs and 80 per cent of these UTIs are attributed to indwelling catheters2. Catheter-associated urinary tract infection complications include genito-urinary tract infections and life-threatening bloodstream infections that develop secondary to a UTI4.

The primary risk factor for CAUTI is the prolonged use of urinary catheters5. With the catheter in place, the daily risk for bacterial growth in the urine or bacteriuria is about 3 to 7 per cent6,7. Ten per cent of patients with bacteriuria will develop CAUTI, while three per cent will go on to develop bloodstream infections. Bloodstream infections result in discomfort, prolonged hospital stays, increased costs and, sometimes, deaths3,4,8.

CAUTI events are costly for both the patient and the entire healthcare system7,9. The clinical consequences and economic burden of CAUTI makes CAUTI prevention fundamental to patient safety. (See Box 1 below for definition of CAUTI)

CAUTI pathogenesis

Indwelling urinary catheters are used therapeutically to drain urine from the bladder; however, when used inappropriately, catheters can pose both mechanical and physiological risks to patients1.

Catheters cause mechanical erosion of the bladder mucosa and ischemic damage when swelling occurs due to blockage. Catheters also provide a route for microbial entry from the colonised perineum to the sterile bladder through a catheter’s internal and external surfaces1. Microorganisms that colonise the perineum and intestinal tract cause about two-thirds of CAUTI, while a third are caused by urine collection systems contaminated by healthcare workers’ hands11.

Urinary catheters interrupt the normal bladder defence mechanism1,11. When bacteria are present in the urinary system, the bacteria bind to the sterile mucosa, which starts an inflammatory response characterised by the inflow of neutrophils and shedding of epithelial cells12. When the catheter is in place, the bacteria bind to catheter surfaces and form a biofilm, which bypasses the normal bladder defence mechanism11.

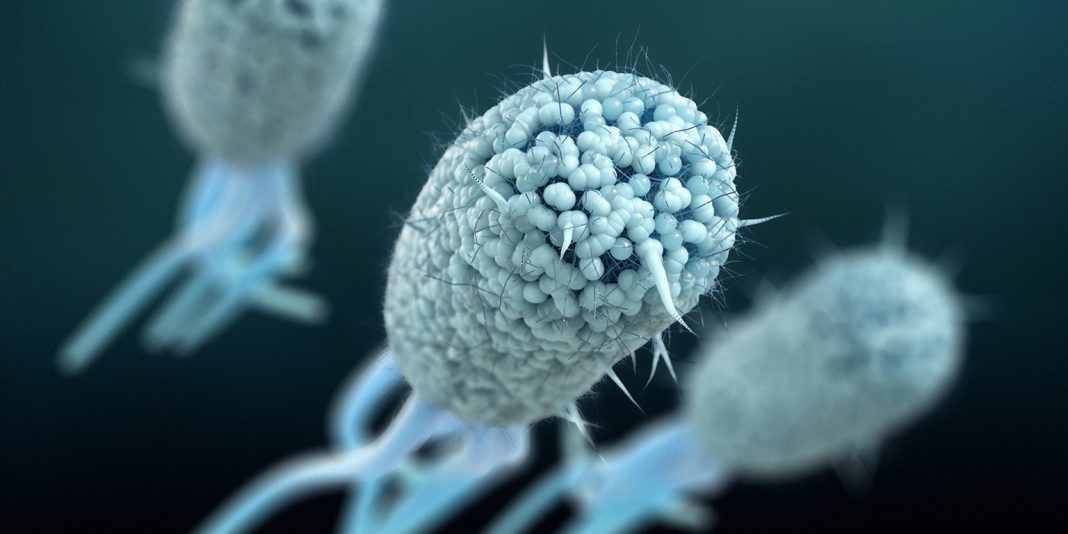

Biofilm

Biofilm formation is central in the development of CAUTI12. Biofilms are slimy structures made up of communities of microorganisms. Biofilm forms when a conditioning film of host components attaches itself to the inner and outer surface of a urinary catheter after insertion. Biofilm traps free-swimming microorganisms that then multiply, attract more microorganisms, and further secrete extracellular matrix that makes the biofilm grow in size. Biofilm microorganisms function as a community and communicate closely with one another1,13. Some microorganisms also detach from the biofilm and seed the urine1.

Biofilms help microorganisms survive through: resistance to being swept away by shear forces; resistance to being engulfed by other cells, and resistance to antimicrobial agents1,13. Studies have shown that antimicrobial agents penetrate biofilms; however, the slow growth of microorganisms in a biofilm confers antimicrobial resistance11. The affinity of microorganisms with each other in a biofilm also permits the exchange of antimicrobial resistance genes, thereby increasing the risk for other CAUTI complications12.

Risk factors for CAUTI

Prolonged catheterisation is the major risk factor for CAUTI3,5. Other risk factors include: non-adherence to aseptic technique during catheter insertion11; poor hand hygiene compliance8; catheter insertion after the sixth day of hospitalisation; poor hand hygiene; catheter insertion outside the operating room9, and a break in the closed drainage system8,14.

Strategies to prevent CAUTI

Multiple strategies have been shown to prevent CAUTI. Prevention strategies were published by the US CDC in 1981 and subsequently updated in 20098 and 20143. These strategies and recommendations were summarised by the USA-based Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI)7 into four components of urinary catheter care. Australia and New Zealand’s 2013 catheterisation guidelines break down the principles for reducing CAUTI into similar sections or components, but with the addition of a section on selecting the appropriate catheter type and drainage system18. The following discussion expands on those components of care to include other evidence-based recommendations.

Component One: Reduce inappropriate use of urinary catheters

Urinary catheter presence in the bladder is the primary risk for CAUTI; thus, reducing inappropriate use is the best way to prevent it11,15.

Catheters should only be inserted when clinically indicated.

Some indications for using short-term catheterisation are:

- acute and chronic urinary retention

- urinary obstruction

- close monitoring of fluid intake and output of critically ill patients

- risk of worsening sacral decubitus ulcer due to urinary incontinence or end-of life care5,8,16,17

- selected surgical procedures that last more than three hours

- management of acute urologic conditions when straight catheterisation is not possible8,16,17

- patients undergoing urologic surgery or surgery on other genitourinary tract structures

- patients anticipated to receive large-volume infusions or diuretics during surgery, and the need for intraoperative monitoring of urinary output.

- urinary catheterisation may also be indicated for patients requiring prolonged immobilisation8.

Inappropriate indications for using indwelling catheters include:

- as a substitute for nursing care of incontinent patients

- as a means of obtaining urine for culture when the patient can voluntarily void8

- for prolonged postoperative duration without appropriate indications8.

Nurses are also encouraged to: use a bladder scanner in assessing urine volume to reduce unnecessary catheter insertions, and consider other bladder management methods such as intermittent catheterisation3,8.

Component Two: Perform proper techniques for indwelling catheter insertion

Indwelling catheter insertion is an invasive procedure that requires care and proper technique to avoid pain, trauma and infection. For more guidance you can view the best-practice urinary catheterisation guidelines [see recommended resources] developed by the Australia and New Zealand Urological Nurses Society (ANZUNS)18.

Selection of catheter

- Select appropriate length and type of catheter for patient.

- Use smallest gauge catheter possible, while ensuring good drainage to minimise bladder neck and urethral trauma3,8.

Hand hygiene

Hand hygiene before and after catheter insertion prevents the introduction of microorganisms into the catheter, thereby minimising CAUTI risk3,8.

Aseptic technique and the use of sterile equipment

Aseptic technique minimises the risk of microbial entry into the sterile urinary system. Aseptic technique during catheter insertion, the use of sterile equipment, and even the setting of catheter insertion all play a significant role in reducing the incidence of bacteriuria19. The use of sterile gloves, drape, sponges, an appropriate antiseptic or sterile solution for periurethral cleaning, and a single-use packet of lubricant jelly for insertion is recommended8.

Secure indwelling catheters after insertion to prevent movement and urethral traction

Indwelling catheters should be kept secure to minimise movement that may cause urethral trauma or erosion of the bladder mucosa7,8,20. Trauma to the bladder mucosa releases organic molecules, which, when combined with glycoprotein from the urine, facilitate bacterial colonisation, thereby increasing CAUTI risk12.

Component Three: Implement proper urinary catheter maintenance procedures

Proper maintenance of urinary catheters focuses on maintaining a closed system and maintaining an unobstructed urine flow8. Ongoing good hand and general hygiene is also very important3,8.

Maintain a closed drainage system

Urinary drainage systems should remain closed because disconnections at the catheter-collecting tube junctions have been shown to significantly increase bacteriuria risk due to bacterial spread along the internal surface of the catheter.

The relative risk of acquiring CAUTI the day after catheter disconnection has been shown to double21. If there are breaks in aseptic technique, disconnection or leakage, nurses should replace the catheter and collection bag using aseptic technique and sterile equipment8.

Microbial spread along the internal catheter surface can also happen if urine in the collection bag is contaminated through improper emptying. In this way microorganisms can gain access to the drainage system and ascend to the bladder, particularly if standard precautions are not observed22. When draining the bag, nurses are also encouraged to avoid splashing urine, to use a separate clean collecting container for each patient, and to prevent contact of the drainage spigot with the non-sterile collecting container3,8,20.

The CDC further recommends that the collection of urine samples should be performed aseptically through the needleless sampling port or the drainage bag using a sterile syringe/cannula after the port is cleansed with a disinfectant8.

Maintain an unobstructed urine flow

Unobstructed urine flow can be achieved through the following measures: keeping the catheter and collection bag free from coils or kinks and off the floor at all times, and emptying the collection bag regularly3,8,20,23.

A study conducted among intensive care patients showed that drainage tubing kinking or coiling was significantly associated with fever and bacteria in the urine23. The presence of kinks and coils is thought to compromise bladder emptying and possibly increase bladder hydrostatic pressure, thereby causing transient bacteriuria, thus the fevers.

The recommendation that the collection tubing and bag should always remain below the patient’s bladder to allow proper urine drainage is supported by a large prospective study in the US showing that improper positioning of the collection tubing and bag is associated with a significantly increased risk in CAUTI because of the backflow of potentially contaminated urine from the drainage bag24.

The authors of a European microbiology study explain that when the drainage bag is placed above the level of the bladder, microorganisms from the urine bag can gain access to the drainage system along the internal catheter surface and ascend to the bladder22.

Component Four: Review catheter necessity daily and remove promptly

The length of time a urinary catheter is in place is the strongest predictor of CAUTI development8. Recommendations indicate that indwelling urinary catheters should be removed as soon as possible post-operatively, preferably within 24 hours unless there are indications for continued use8. It has been found that patients develop bacteriuria at a rate of three to seven per cent per day7. This risk increases to 25 per cent when the catheter remains in place for one week and increases to nearly 100 per cent when the catheter remains in place for up to a month7.

Effective catheter care involves collaborative effort8; however, nurses remain largely responsible for indwelling catheter care. Daily assessment of catheter need and the possibility of removal is recommended3, with electronic alerts or other daily reminder systems important in acute care. Nurses are also advised to use standard precautions during catheter removal to prevent cross-transmission of microorganisms, thereby preventing CAUTI8.

Conclusion

In summary, the components of care to prevent CAUTI include: reduction of inappropriate use of urinary catheters; performance of proper indwelling catheter insertion techniques; selection of correct catheter and drainage system; implementation of proper catheter maintenance procedures, and removal of catheters in a timely manner.

These catheter management components are all inter-related and can help to prevent this most common of the healthcare-associated infections – CAUTI.

In addition, education on CAUTI prevention should not only focus on one aspect of care, but should also be spread across all components

of care.

Box 1: CAUTI definition

The definition of CAUTI varies worldwide, as does the criteria for identifying CAUTI. One of the more commonly used definitions in acute care settings is that of the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) of the United States Government’s Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The NHSN define CAUTI as a urinary tract infection in a person with an indwelling urinary catheter for more than two days and at least one of the following criteria:

- With catheter still in place, the person develops at least one of the following – fever (> 38C), suprapubic tenderness, costovertebral angle pain, and a positive urine culture of > 105 colony-forming units (CFU)/ml with no more than two species of microorganisms.

- With catheter removed the day prior to, or on the day, the person manifests at least one of the following – fever (> 38C), urgency, frequency, dysuria, suprapubic tenderness, costovertebral angle pain, and a positive urine culture of > 105 CFU/ml with no more than two species of microorganisms (reference 10).

View the PDF of this article (and related learning activity) here >>

Recommended resources:

Detailed best-practice urinary catheterisation guidelines from the Australia and New Zealand Urological nurses Society (ANZUNS) can be downloaded from their website at www.anzuns.org

Evidence-based guidance on the prevention of healthcare-associated infections in primary and community care can be found at the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) website at www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg139/evidence

The CDC website also offers resources for both patients and healthcare workers. The CDC guideline for CAUTI prevention is downloadable from their website at https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/cauti/index.html

About the authors:

- Monina Gesmundo RN, BSN, PGCertTT, PGDipHSc, MNur (Hons) until recently worked as a clinical nurse specialist for infection prevention and control at Counties Manukau Health. She is currently a lecturer at the School of Nursing, Massey University.

- Dr Anna King is a lecturer at the School of Nursing, the University of Auckland.

Lisa Stewart, RN, BA, PGDipHSc, MNur (Hons) is a professional teaching fellow and PhD candidate at the School of Nursing, the University of Auckland.

This article was peer reviewed by:

- Ruth Barratt RN BSc MAdvPrac (Hons), a clinical nurse specialist infection prevention and control for the Canterbury District Health Board.

REFERENCES

- SIDDIQ D & DAROUICHE R (2012). New strategies to prevent catheter-urinary tract infections. Nature Reviews Urology, 9, 305-314.

- WEBER D, SICKBERT-BENNETT E, GOULD C ET AL. (2011). Incidence of catheter-associated and non-catheter-associated urinary tract infections in a healthcare system. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 32(8), 822-823.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/661107 - LO E, NICOLLE L, COFFIN S ET AL. (2014). Strategies to prevent catheter- associated urinary tract infections in acute care hospitals: 2014 update. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 35(5), 464-479. doi:10.1086/675718

- CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL (2013). April 2013 CDC/NHSN protocol corrections,clarification, and additions. Retrieved from

https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/7psccauticurrent.pdf - MOHAJER M & DAROUICHE R (2013). Prevention and treatment of urinary catheter-associated infections. Current Infectious Disease Reports, 15(2), 116-123.

- REBMANN T & GREENE L (2010). Preventing catheter-associated urinary tract infections: An executive summary of the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology, Inc, elimination guide. American Journal of Infection Control, 38(8), 644-646.

- INSTITUTE FOR HEALTHCARE IMPROVEMENT (2011). How to guide: Prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infection. Retrieved from http://www.ihi.org/Topics/CAUTI/Pages/default.aspx

- GOULD C., UMSCHEID C, AGARWAL R, ET AL. (2009). Guideline for prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Retrieved from

www.cdc.gov/hicpac/pdf/cauti/cautiguideline2009final.pdf - BURTON D, EDWARDS J, SRINIVASAN A ET AL. (2011). Trends in catheter-associated urinary tract infections in adult intensive care units – United States, 1990–2007. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 32(8), 748-756

- CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL (2015). Urinary tract infection (catheter-associated urinary tract infection and non-catheter-associated urinary tract infection and other urinary system infection events. Retrieved from

www.cdc.gov/nhsn/PDFs/pscManual/7pscCAUTIcurrent.pdf - CHENOWETH C & SAINT S (2013). Preventing catheter-associated urinary tract infections in the intensive care unit. Critical Care Clinics, 29(1), 19-32 doi:10.1016/j.ccc.2012.10.005

- TRAUTNER B & DAROUICHE R (2004). Role of biofilm in catheter-associated urinary tract infection. American Journal of Infection Control, 32, 177-183.

- NIKOLAEV Y, & PLAKUNOV A (2007). Biofilm -“City of microbes” or an analogue of multicellular organisms? Microbiology, 76(2), 125-138.

- KING C, GARCIA ALVAREZ L, HOLMES A ET AL. (2012). Risk factors for healthcare-associated urinary tract infection and their applications in surveillance using hospital administrative data: a systematic review. Journal of Hospital Infection, 82, 219-226.

- BERNARD M, HUNTER K & MOORE K (2012). A review of strategies to decrease the duration of indwelling urethral catheters and potentially reduce the incidence of catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Urologic Nursing, 32(1), 29-37.

- TITSWORTH W, HESTER J, CORREIA T ET AL. (2012). Reduction of catheter-associated urinary tract infections among patients in a neurological intensive care unit: A single institution’s success. Journal of Neurosurgery, 116(4), 911-920.

http://dx.doi.org/10.3171/2011.11.JNS11974 - MURPHY C, FADER M & PRIETO J (2013). Interventions to minimise the initial use of indwelling urinary catheters in acute care: a systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 1-10.

- AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND UROLOGICAL NURSES SOCIETY CATHETERISATION GUIDELINE WORKING PARTY (2013). Catheterisation Clinical Guidelines. ANZUNS, Victoria.

www.anzuns.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/ANZUNS-Guidelines_Catheterisation-Clinical-Guidelines.pdf - BARBADORO P, LABRICCIOSA F, RECANATINI C, ET AL. (2015). Catheter-associated urinary tract infection: Role of the setting of catheter insertion. American Journal of Infection Control, 43(7), 707-710.

- HOOTON T, BRADLEY S, CARDENAS D ET AL. (2010). Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of catheter-associated urinary tract infection in adults: 2009 international clinical practice guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 50(5),625-663. doi:10.1086/650482

- PLATT R, MURDOCK B, FRANK POLK B, & ROSNER B (1983). Reduction of mortality associated with nosocomial urinary tract infection. The Lancet, 321(8330), 893-897. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(83)91327-2

- WENZLER-RÖTTELE, DETTENKOFER, SCHMIDT-EISENLOHR ET AL. (2006). Comparison in a laboratory model between the performance of a urinary closed system bag with double non-return valve and that of a single valve system. Infection, 34(4), 214-218.

- KUBILAY Z, LAYON A, KUBILAY Z ET AL. (2013). What we don’t know may hurt us: Urinary drainage system tubing coils and CAUTIs – A prospective quality study. American Journal of Infection Control, 41(12),1278-1280. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2013.06.009

- MAKI D, & TAMBYAH P (2001). Engineering out the risk for infection with urinary catheters. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 7(2), 342.