By Louise Carrucan-Wood

Reading this article and undertaking the learning activity is equivalent to 60 minutes of professional development

Learning objectives

Reading and reflecting on this article will enable you to:

- Reading and reflecting on this article will enable you to:

- Identify the roles and responsibilities of a preceptor

- Introduce the concept of mentorship within nursing

- Identify teaching strategies to assist you to support a beginner nurse to learn within a clinical practice area.

Introduction

Experienced nurses can recall their own transition from beginner to proficient nurse, where learning occurred by observation, imitation, and role modelling; resulting in growing confidence and competence. When one is new to nursing practice, becoming a confident and effective nurse relies on professional knowledge, skills and responsibilities being passed on from others. Bandura1 suggests that learning can take place simply by being with others and watching them. Loosely referred to as a ‘socialisation’ to the nursing profession, those who are new to nursing accommodate and adjust their understanding of what it means to be a nurse. This is best illustrated when a beginner nurse observes a competent nurse, whom they identify as a role model, and adapts their nursing practice.

Self-efficacy develops as new nurses gain experience, observe others’ success and put in sustained effort; and self-efficacy is widely noted to be the most important predictor of behaviour change. For this reason, knowledge and skills are important, but self-efficacy is the strongest predictor of actual success, and self-efficacy develops best when a learner is engaged2. Bandura’s social cognitive model identifies three factors that influence self-efficacy – behaviours, the learning environment, and personal or cognitive factors. Conversely, a lack of self-belief, disengagement from social learning experiences and a lack of attention can all lead to failure to learn.

It is no surprise then that any negative effect of the ‘reality shock’ of starting their first nursing job is diminished when nurses complete a formal orientation period, are supported by a preceptor (and/or mentor), with close supervision from a senior nurse, and have the opportunity to reflect and debrief. An effective orientation programme has the ability to boost the confidence of the beginner nurse, to promote effective role transition, to increase job satisfaction and reduce attrition3.

Benner recognises that most beginner nurses are at an advanced beginner level stage in their initial practice. She points out that new graduates come with some practical knowledge of clinical nursing, but they are still guided by rules, and are still applying theory to new contexts so require side-by-side clinical instruction from expert nurses who can lead by example4. It is also acknowledged that gaining clinical skill proficiency is deeply embedded in clinical experience so guiding a beginner nurse requires repeated exposure to role modelling over time5.

Preceptors and mentors

The importance of preceptors and mentors cannot be overstated as these team members are critical to the orientation and nurturing of new graduate nurses, and play a key role in the transition from advanced beginner to proficient nurse. Confusingly, the terms preceptor and mentor are often used in the research literature as if they are interchangeable, yet they do have different meanings. Both preceptors and mentors are role models who enable and facilitate learning.

Preceptorship

In this article a preceptor is defined as an experienced and skilled nurse who provides specific teaching and learning opportunities for a beginner nurse over a defined period of time, within a specific clinical context. These learning strategies occur alongside the learner in a planned way. Time is planned to reflect, debrief and discuss the learning event, so that the learner can recognise the reasoning behind the clinical decisions made and the care delivered. In essence, meaning is created from the learning experience.

The preceptor guides this process of transformational learning, by encouraging the learner to critically think about any assumptions or rationale about the learning event. Essentially transformational learning shapes the beginner nurse (learner), so the learning experience produces more far-reaching changes than does learning in general6. More simply put, the role of the preceptor is to bridge the gap between idealism and reality through role modelling, coaching, demonstration, and communication7.

The preceptor – learner relationship is characterised by how the preceptor uses the unique one-to-one peer relationship to gradually socialise the learner into the many dimensions and aspects of the role8. Preceptorship is commonly understood to be for a limited period of time during which a new graduate nurse in their first nursing job is supported by an experienced nurse to consolidate their knowledge and skills.

Mentorship

A key point of difference between a preceptor and a mentor is that the characteristics of a mentor relationship are central to the success of mentorship. A mentor has commonly been regarded as someone who encourages and offers direction and advice. Mentoring relationships develop and grow between individuals over sometimes long periods of time, providing emotional and professional support. Interestingly, mentorship within healthcare can be considered different from classic mentoring, as mentorship relationships can be defined over shorter periods of time and also being able to select your own mentor is not always possible. An example of this is student nurses who may have a ‘mentor’ while in clinical placements for 2–8 weeks. But for the purpose of this article a mentor relationship is one that develops over time, providing emotional and professional support.

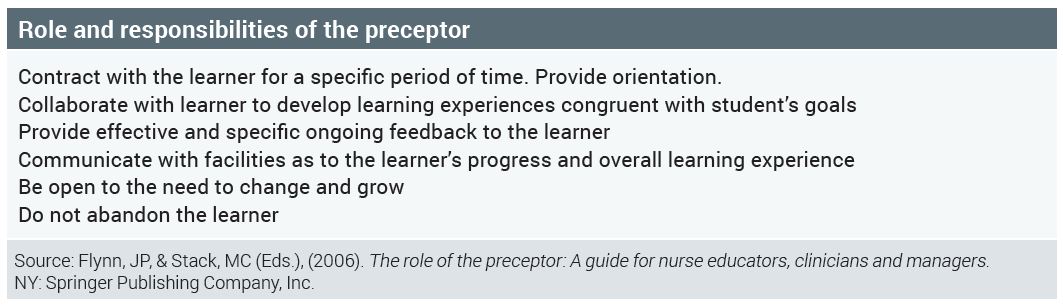

Role and responsibilities of the preceptor

- Contract with the learner for a specific period of time. Provide orientation.

- Collaborate with learner to develop learning experiences congruent with student’s goals

- Provide effective and specific ongoing feedback to the learner

- Communicate with facilities as to the learner’s progress and overall learning experience

- Be open to the need to change and grow

- Do not abandon the learner

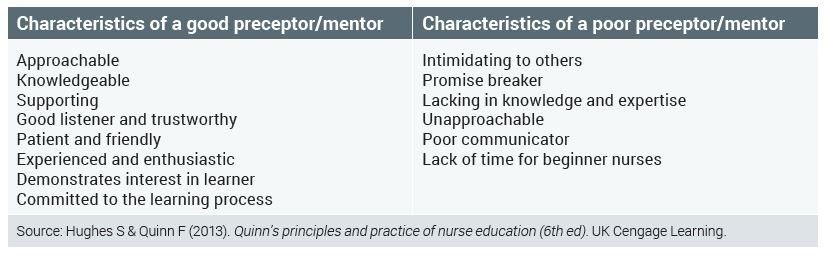

Characteristics common to both

Whether being a preceptor or a mentor is of interest to you, it is important to recognise their common characteristics. Both roles act as enablers of learning and require practitioners who communicate in an open and honest way, are self-confident and positive, are accessible and responsive to the learner’s needs, are trustworthy and able to respect others, and who also seek respect.

A simple point of difference is that a preceptor is a teacher of nursing practice, while a mentor is a trusted guide or counsellor who assists the learner to develop by recognising the learner’s strengths and weaknesses, usually throughout their career9.

Good preceptorship is vital

Although preceptorship is a common and an essential component of education programmes for nurses and other health professionals, there is little empirical evidence in the literature about the effectiveness of any particular approach10. Preceptorship can involve both individual and group educational and support methods. A group orientation model for new graduate nurses, using concepts and techniques familiar to individual preceptorship relationships, has demonstrated benefit to the new graduate nurse and organisation11. The benefits of preceptorship – particularly communication skills, assessment of learning, and providing feedback – were noted to be effective12.

The power of high-quality preceptors and positive preceptor-learner relationships cannot be understated and because of this careful selection and preparation of preceptors is crucial to the success of any orientation programme13. The need for formal preceptor development programmes is well stated in the literature. Preceptors require the necessary resources and tools to assist them to effectively demonstrate nursing care and teach new skills. In the past senior nurses have commonly been allocated as preceptors, while those with less experience were overlooked for the role14. Benner, as cited by Baxter, suggested that nurses with two to four years of clinical experience are best suited to the preceptor role, because as advanced beginners they provide care while ‘thinking out loud’14. This is in contrast to expert nurses who are considered, by Benner, as less able to break down clinical tasks and explain their response to different situations.

Learning in clinical practice areas

When preparing to be a preceptor or mentor, it is important to consider what practice learning experience can be offered, so that you are clear what you can provide for the learner and what is realistic for them to achieve. Although the Nursing Council of New Zealand has defined the scope of practice for nurses in education roles, the Nursing Midwifery Council, United Kingdom (2008) defined four mentor domains that are useful to consider when readying a clinical practice area for the arrival of a beginner nurse:

- Establish effective working relationships – demonstrate effective working relationships with wider inter-professional team

- Facilitation of learning – where appropriate, encourage self-management of learning opportunities and provide support to maximise the learner’s potential

- Creating an environment for learning – where practice is valued and developed to provide appropriate professional and inter-professional learning opportunities

- Context of practice – support learning within a context of practice that reflects healthcare and educational policies and manage change to ensure particular professional needs are met within a learning environment that also supports practice development15.

Collectively, the nursing team plays a vital role in the culture and characteristics of a workplace environment conducive to learning. Additionally, members of the wider health care team also contribute to the learning environment, assisting learners to feel part of the whole team. One of the responsibilities of a preceptor is to create and enhance a positive learning environment so that learning is maximised.

Creating a learning environment

Before a beginner nurse arrives in your clinical area, some preparation is required to ensure that the clinical practice area is an effective learning environment. Start by asking yourself these questions:

- What opportunities are there for learning in my practice area?

- What activities could be undertaken for the beginner nurse to learn?

- Do I understand the requirements of the learning programme?

- Do I understand my accountability and responsibility as a preceptor?

- Do I know how to access support?

Effective teaching strategies for preceptorship

Nurses who preceptor often express a lack of confidence and a need for greater preparation for the role17. A lack of job description about the preceptor role, or formal training for the role has been noted by Yonge et al18. Recommended content for preceptor preparation includes teaching/learning in clinical experiences, using observation and participation, engaging beginner nurses in learning experiences, prompting positive feedback from students, using reflective learning, promoting self-efficacy and a sense of accomplishment, and working with beginner nurses who are perceived to be unprepared or unsafe19,20.

What follows is a brief outline of some effective teaching strategies that preceptors can use to support beginner nurses in clinical practice 21:

1: Learning contracts

A learning contract can be a verbal (informal) or written (formal) agreement, designed by the preceptor (or their organisation) and beginner nurse to specify what will be learnt and how it will be achieved, over a defined period of time. A learning contract is an effective tool for developing self-efficacy; it can be negotiated and modified throughout the preceptorship. It can be referred to frequently throughout the preceptorship and can inform both the planning of teaching strategies and evaluation of learning.

2: Teaching 1:1

This demands different skills from group teaching, as much of one-to-one teaching is opportunistic and most typically occurs as everyday practice. Teaching can be initiated by the preceptor or beginner nurse and may happen in the presence of other staff, patients/clients and family/whānau. The need to appear competent and credible to all can add pressure to the situation. As a teacher/preceptor it is important to be aware of the critical aspects that require explanation during this learning experience, so to ensure that the nursing care of patient/client, family/whānau remains paramount.

3: Case studies

Ideally a case study involves bringing together members of the nursing team to discuss and evaluate aspects of nursing care. There is no standard format to follow, but involving a whole team discussion provides a holistic view of the patient/client.

4: Nursing handover

Verbal handover is a useful teaching strategy, where the preceptor can model effective handover techniques and also act as an observer when the novice learner demonstrates handover. A nursing handover provides opportunity for the beginner nurse to voice priorities and issues in care, within their scope of practice, while receiving feedback on their plan for ongoing nursing care.

5: Reflective practice diary

Reflective diaries consist of brief written descriptions of nursing practice situations that can be used as a basis for reflection. Examples could include the beginner nurse’s first experience of a clinical experience. Asking the beginner nurse to also record their observations of the preceptor’s nursing care may help them identify key learning concepts before they need to apply the concepts themselves to a new situation.

6: Critical incident technique

Critical incident technique is a useful way for the beginner nurse to identify aspects of nursing practice that can be either strongly positive or negative. The focus of learning is the incident and should include a detailed description of the event. Discussing why the incident was critical to the beginner nurse, what the beginner’s nurse concerns were at the time, what they were thinking about during the incident, what they felt and what they found most demanding about the incident, are all valuable. Benner, as cited by Hughes and Quinn, identified critical incidents to be those:

- in which the nurse’s intervention really made a difference to patient outcome

- that went unusually well

- in which there was a breakdown

- that were ordinary and typical

- that captured the essence of nursing

- that were particularly demanding.

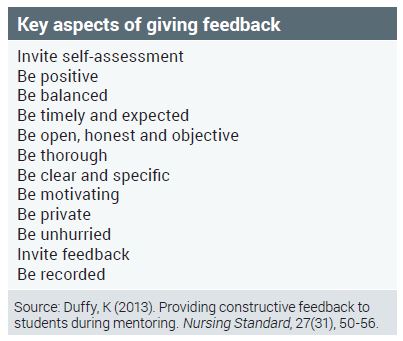

7: Providing constructive feedback

Continuous assessment is an ongoing process where ‘snapshots’ of practice are taken, followed by constructive feedback which can occur formally and informally. Orientation programmes usually clearly state when formal feedback is to be given. Regular constructive feedback has many benefits as it can assist the beginner nurse to maintain and increase their motivation, and increase their confidence and self-esteem. When providing constructive feedback it is important to include a specific example and communicate a positive tone.

A useful way of providing feedback is the ‘mutual learning approach’ – this approach works because instead of identifying what is missing, it requires the preceptor to think of feedback as a way for them and the beginner nurse to make informed choices together. The result can be that feedback is more genuine, levels of anxiety or discomfort are lowered and respect is built22.

How to respond if a beginner nurse is not meeting the criteria?

If you identify a problem with the beginner nurse’s performance, negotiate an action plan with the beginner nurse, including a written contract. Involve the nurse educator or nurse manager to support you and to also ensure objectivity in your assessment of the situation. This can be a stressful time but can be managed with minimal trauma to both you and the beginner nurse. It is important that you remain objective and honest and that you have facilitated a range of learning activities and opportunities for the beginner nurses to achieve. The reasons why a beginner nurse may not meet a criterion may not be so obvious at first. Managing this situation can be broken down into clear stages:

- Early detection – meet early in the preceptor relationship to discuss progress. It is important to identify any deficit and to also give the beginner nurse sufficient time or guidance.

- Meet regularly – by meeting regularly progress and achievement of outcomes can be discussed.

- Identify learning needs – having identified non-achievement of outcomes, learning needs should be identified to inform an action plan.

- Be objective and supportive – seek the views and experiences of others and also of the beginner nurse. Offer support and resources, working closely with the beginner nurse.

Conclusion

While preceptorship and mentoring are not new to nursing, this article has provided an introductory focus on preceptorship. By ensuring their clinical practice areas are positive learning environments, nurses are able to employ learning strategies that benefit both beginner nurses and the wider nursing team. As team members we all contribute to the learning experience of newly employed team members; being a role model who enables learning is of benefit to all.

View the PD learning activity here >>

About the author:

Louise Carrucan-Wood, RN, BN (Distn), MHSc (First Class Honours) is a professional teaching fellow and a PhD candidate at the School of Nursing, The University of Auckland.

This article was peer reviewed by:

- David Mitchell RN, BN, MA (Applied), Senior Academic Staff member, NMIT

- Lesley Macdonald RN, MSocSc, NETP and NESP Coordinator for Waikato DHB

REFERENCES

- BANDURA A (1997). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavior change. Psychological Review, 84, 191-215.

- Nursing theories a companion to nursing theories and models (n.d.). Retrieved 02 July 2015 from: http://nursingplanet.com/theory/self_efficacy_theory.html

- GAVLACK S (2007). Centralised orientation: Retaining graduate nurses. Journal for Nurses in Staff Development, 23(1), 26-30.

- BENNER P (2001). From novice to expert: Excellence and power in clinical nursing practice. NJ: Prentice Hall.

- WINFIELD C, MELO K & MYRICK F (2009). Meeting the challenge of new graduate role transition. Journal for Nurses in Staff Development, 25(2), E7-E13.

- CLARK MC (2006). Transformations Learning. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 57, 47-56. doi: 10.1002/ace.3671993570

- FLYNN J, & STACK M (Eds.), (2006). The role of the preceptor: A guide for nurse educators, clinicians and managers. NY: Springer Publishing Company, Inc.

- O’CONNOR A (2015). Clinical instruction and evaluation: A teaching resource (3rd ed.). MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning.

- RACE T & SKEES J (2010). Changing tides: Improving outcomes through mentorship on all levels of nursing. Critical Care Nursing Quarterly, 33(2), 163-174.

- DEWOLFE J, PERKIN C, HARRISON M ET AL (2010). Strategies to prepare and sup

- WOODWORTH J (2012). A group orientation model for new graduate nurses. Journal for Nurses in Staff Development, 28(5), 219-221.

- KILGALLON K & THOMPSON J (2012). Mentoring in nursing and healthcare:

A practical approach. UK: John Wiley & Sons. - FEY M & MILTNER R (2000). Centralised orientation: Retaining graduate nurses. Journal of Nursing Administration, 30(3), 126-132.

- BAXTER P (2010). Providing orientation programs to new graduate nurses. Journal for Nurses in Staff Development, 26(4), E12-E17.

- ASTON L & HALLAM P (2011). Successful mentoring in Nursing: Helping you to mentor degree-level nursing students. GB: Learning Matters Ltd.

- ELCOCK K & SHARPLES K ( 2011). A nurse’s survival guide to mentoring. China: Elsevier.

- KELLY C (2006). Students’ perceptions of effective clinical teaching revisited. Nurse Education Today, 27, 885 – 892.

- YONGE O, MYRICK F, FERGUSON L & LUGHANA F (2005). Providing effective preceptorship experiences. Journal of Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nursing, 32(6), 407-412.

- EARLE-FOLEY V, KEE C, MINICK P, HARVEY S, JENNINGS B. (2012). Preceptorship: using an ethical lens to reflect on the unsafe student. Journal of Professional Nursing 28(1), 27-33.

- LUHANGA F, YONGE O & MYRICK F (2008). Strategies for preceptoring the unsafe student. Journal for Nurses in Staff Development, 24(5), 214-219.

- HUGHES S & QUINN F (2013). Quinn’s principles and practice of nurse education.) (6th ed.) UK: Cengage Learning.

- DUFFY K (2013). Providing constructive feedback to students during mentoring. Nursing Standard, 27(31), 50 -56.