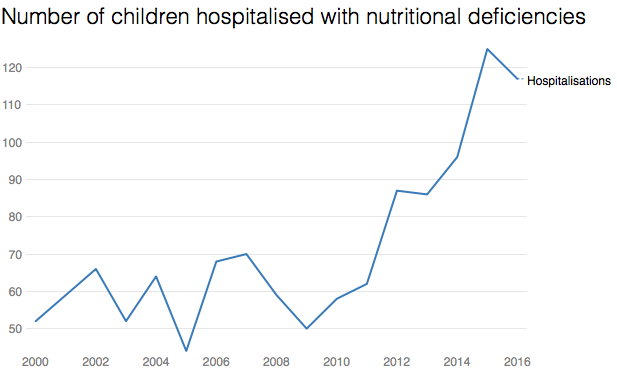

Malnutrition is putting twice as many kids in hospital compared with 10 years ago, as food prices continue to bite into household incomes.

Child hospitalisation data shows around 120 children a year now have overnight stays due to nutritional deficiencies and anaemia, compared to an average 60 a decade ago.

Doctors say poor nutrition is also a factor in a significant proportion of the rest of the 40,000 annual child hospitalisations linked to poverty – and that vitamin deficiencies are more common in New Zealand compared to similar countries.

“Housing, stress and nutrition – it’s all tied together,” said pediatrician Dr Nikki Turner, from the Child Poverty Action Group. “If you want to eat nutritiously on a low-income it’s difficult, and that means you’re more likely to get sick and stay sick for longer.”

The new health data comes as food prices continue to rise, with the consumer price index last week indicating food costs were up 2.3 per cent on a year ago. At the same time, income in the poorest third of households has remained flat since 1982.

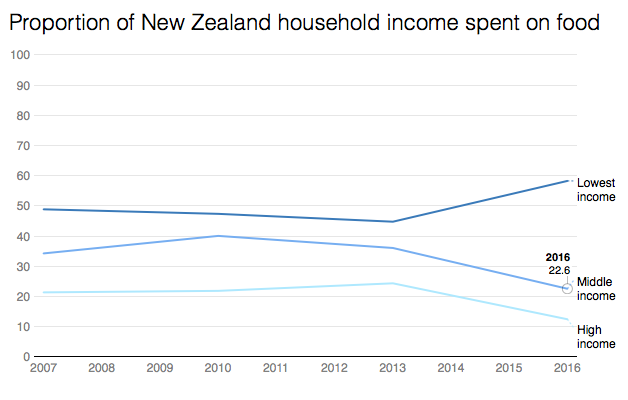

Statistics New Zealand information released to the Herald shows for families on the lowest incomes (under $35,000), that means they’re now spending 60 per cent of their income on food, compared to 48 per cent in 2007.

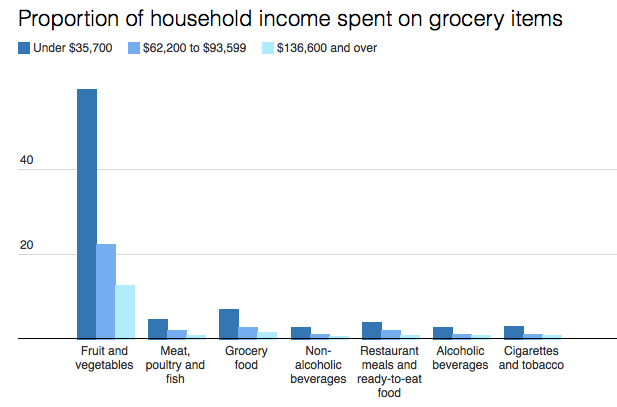

More than half of that goes on fruit and vegetables, data shows. Among middle-income families, 22 per cent of income goes on food, with one fifth of that on fruit and vegetables.

An Australian paper has suggested that “food stress” is believed to be experienced when more than 30 per cent of income is spent on groceries.

In practice, “food stress” means increasing reliance on food banks, charities, cheap “fillers” like white bread and noodles, or simply going without.

“I try to fill up the pantry but it only lasts one or two days and then it’s empty again,” said solo dad of three kids, Daniel*, from Otara. “I have to skip my own lunches because the kids are always hungry and I try to prioritise school lunches for them. I know that’s important.”

Dr Cameron Grant, the head of paediatrics at Auckland University, said it was rare for children to be hospitalised for severe nutritional issues in New Zealand, malnutrition was a factor in a significant proportion of illnesses.

“A third of children hospitalised at Starship have iron deficiency, for example,” Grant said. “A lack of vitamin D is also very common. That increases the risk of respiratory illnesses.”

New Zealand rates of iron deficiency are twice as high as Europe, the UK and Australia, he said, and Vitamin D deficiency was higher than the USA, because our food lacked nutrients.

However, New Zealand diets were also energy rich, meaning children could be both undernourished and obese – a situation that was not improving.

Child Poverty Action Group’s Turner said contrary to popular opinion, it wasn’t an issue of poor budgeting causing the problem.

According to household income data, low-income families spent about the same on cigarettes and alcohol as middle-income earners, for example.

“Low income families are not wasting money any more than anyone else, but it just doesn’t stretch far enough,” she said.

The University of Otago 2016 Food Survey estimates the basic weekly food cost for a man is $64 per week. For a woman it’s $55, and a 5-year-old is $40.

Research at the Auckland City Mission found families coming for food parcels have an average $24 per person each week for all groceries. That’s around $3.50 a day.

However, Massey University PhD candidate Rebekah Graham, who researches food insecurity, said some people had even less – such as one woman who had only $25 a week for herself and two children.

The food she bought – tinned fruit, bacon-and-egg pies, noodles – was barely enough to meet the family’s food requirements. Despite that, the woman still bought a cake as a gift for friend suffering a bereavement.

Graham’s research found families frequently had to make terrible choices to survive. One woman, surviving on $1 loaves of white bread, was unable to produce enough milk to feed her baby. Others put off urgent dental work. She also heard of people taking sleeping pills on a Friday so they could sleep through the weekend and not have to pay for food.

Chief executive of Variety, the Children’s Charity, Lorraine Taylor said food was always the first thing to go if families needed something – whether that was school uniforms or doctor’s bills. They also heard of parents not eating to feed their kids.

The charity, which runs a child sponsorship programme but is increasingly propping up families with food vouchers, said it was unacceptable that charities were left to fill the gap.

“Food should not be a negotiable. We want to live in a country where all Kiwi children are fed nutritious food.”

The Ministry of Health’s principal nutrition advisor Elizabeth Aitken said it last carried out a national children’s nutrition survey in 2002, and did not have more recent data on quantified nutrient intakes for children.

It said diet was just one of a range of causes of anaemia and nutritional deficiencies, but it knew obesity was increasing from poor quality diets.

The ministry had a range of programmes to help parents with advice on nutrition and development, she said.

Daniel’s family

The kids are always hungry at Daniel’s house, but the cupboards are almost never full.

A solo dad to three school-aged kids, he struggles to make the groceries last the week, even though he skips his own lunches and uses all the leftovers – and attended a budgeting course to learn how to make money go further.

“Sometimes I have to lock the cupboard to make sure we have enough,” he says. “I find it hard.”

Daniel – which is not his real name – has at most $200 to spend a week on food, depending on bills or how much work he gets. He earns about $500 a week. His rent it $180, for a three-bedroom in Otara.

The only fruit he buys are apples and oranges, even though his kids love grapes, and they eat toast and spaghetti for dinner most nights a week. A cooked chicken is a luxury, only for special occasions. The kids never buy their lunches, instead having bread and cheese, maybe a muesli bar, and a piece of fruit.

“I know it doesn’t look good if they don’t have lunch,” Daniel says. “I have to skip my own lunches because the kids are always hungry and I try to prioritise school lunches for them. I know that’s important.”

A sponsorship – through the charity Variety – has helped, helping with the children’s shoes and clothes, and occasional supermarket vouchers.

Sometimes, however, the bills push him to line up at the food bank for a parcel, even thought he hates it.

“I feel embarrassed at times, but I just had to tell myself that we are desperate,” he says. “I have no choice.”