Why do we need hydration?

Water is an essential nutrient which the body loses and cannot produce in the amounts it requires. It accounts for up to 80% of body weight and fills the spaces between cells, supports biochemical reactions and forms structures of large molecules like protein. Water is essential for physiological processes such as digestion, absorption and transportation.

If we do not consume water, or water containing foods or fluids regularly throughout the day, we become dehydrated.

Dehydration occurs in two ways, either the body is short of fluid because of “low intake” and failure to drink sufficient fluids, or due to increased fluid loss known as “volume depletion” caused by diarrhoea, vomiting or excessive bleeding.

What really happens when we become dehydrated?

Whatever way dehydration occurs it is serious. In normal healthy adults thirst is the signal that stimulates us to seek fluids. Thirst is stimulated when osmolality increases or the extracellular volume decreases. Unfortunately older people often have impaired thirst mechanisms and the signal to seek fluids is defective, which leads to dehydration.

Also when there is insufficient fluid intake or excessive fluid loss, the kidneys compensate by producing a more concentrated urine to maintain the individual’s fluid balance. However, in older people the kidneys ability to concentrate urine is impaired and dehydration occurs.

What are the risks of dehydration?

Older people who don’t drink enough (or have increased fluid losses) have an increased risk of:

- Pressure injuries

- Low blood pressure, Dizziness and Falls

- Cognitive impairment, confusion and delirium

- Constipation

- Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs) and acute kidney injury

What puts older people at risk of dehydration?

There are a wide range of reasons why older people are at higher risk of dehydration than younger adults, including:

- Decreased thirst sensation.

- Dysphagia – reduced ability to swallow thin fluids with aspirating and not enjoying prescribed thickened fluids

- Medication commonly required by older people such as diuretics and laxatives

- Hot weather – extreme summer temperatures will increase fluid requirements for some older people

- Fever, diarrhoea and vomiting increase fluid losses, so more than usual fluid intake is required to make up for these losses.

- Decreased renal function in older people

- Cognitive issues with forgetting to drink or losing the ability to drink independently

- Inability to access or communicate the need for drinks

- Concerns around continence – older people restrict fluid intake due to fear of having an accident.

- Inadequate staffing to meet recommended regular fluid rounds and assist residents to drink throughout the day

How do we know if the older person is dehydrated?

Simple signs and tests to assess dehydration such as skin turgor (how quickly your skin returns to normal position), urine colour or weight change are not sufficient indicators of “low intake” dehydration. A blood test (serum osmolality) is the gold standard measure to assess hydration status if necessary. However, all older people living in residential aged care facilities should be considered at risk of low intake dehydration (ESPEN 2018).

How much fluid do older people need and how do they get it?

It’s estimated that 20% of fluid requirements will come from food and 80% of daily fluid needs from drinks.

Minimum Fluid requirements:

- Females: 1.6L/ day

- Males 2L/day.

On average an intake of 30 mls/kg body weight is required to maintain fluid balance, individuals will vary in their requirements.

Fluids are not just limited to water, and for any older people at risk of malnutrition they should contain energy and protein (e.g. yoghurt, custards, ice-cream, smoothies etc.).

Making drinks more exciting by adding colour, flavour and for some people increasing the sweetness, may support increased intake.

Tips for reducing the risk of dehydration

- Put hydration plans in place for each resident with individual goals and regularly assess and review resident’s fluid needs.

- Continuous use of prompts for residents, from carers and relatives, encouraging them to regularly consume drinks.

- Set up hydration stations for residents and visitors in shared areas with drinks the residents enjoy.

- Encourage visitors to have a drink with residents they are visiting.

- Provide assistance with drinking and put in place flags. For example, use different coloured coasters for patients at risk of dehydration.

- Implement bedside wall charts identifying residents needing extra support to meet daily fluid goals.

- Educate all members of the team; residents, relatives and all staff on the importance of fluid consumption.

- Appoint a “Hydration Champion” in the care team to monitor hydration audit outcomes.

Then if you still continue to have concerns about a resident’s fluid intake consult with the facilities Doctor, Consultant Dietitian and/or Speech Language Therapist.

Want to take action now?

- Conduct regular fluids rounds every hour to 90 minutes during the day or as indicated in the facilities Hydration guidelines

- Remind residents, carers, family members/whanau it is everyone’s responsibility to ensure residents get the fluids they need.

- Access to water is a basic human right – Resolution 64/292, the United Nations General Assembly 2010

About The Pure Food Co

The Pure Food Co is a pureed food and fortified ingredient company on a mission to nourish our older people with NZ’s quality produce and best-in-class nutritional science. Visit www.thepurefoodco.co.nz or call 0800 178 733 for more information.

Try the Award Winning Peanut Butter Slab Smoothie

During these hot summer months, we ran a smoothie competition where aged care chefs and kitchen staff were invited to enter in their best smoothie creation so they could be in the running to win a grand prize worth $800!

We took the Top 3 smoothie recipes to the Highgrove Village & Patrick Ferry House & the awesome residents were our judges, voting for the smoothie they enjoyed the most!

The votes are in and the winner is… The Peanut Slab Smoothie by Nikolai Balanski from Ryman Healthcare Ltd Princess Alexandra won!

Congrats Nickolai, your delicious & nutritious Peanut Butter Slab Smoothie was a true crowd pleaser. Using our Choc Brownie dessert as the fortified smoothie base, his recipe provides 12.6g of protein per serve!

Check out the full story here.

By Krinessa Valenzuela and Monina Hernandez

________________________________________________________________________

Reading this article and undertaking the learning activity is equivalent to 60 minutes of professional development.

Learning outcomes

Reading and reflecting on this article will help nurses to:

- Increase awareness of the challenges multicultural patients experience as inpatients.

- Identify the barriers that affect the health outcomes of multicultural patients.

- Identify strategies or interventions to remove the barriers.

The learning activity is relevant to the Nursing Council competencies 1.5, 2.1, 2.2, 2.3, 2.6 and 3.2.

________________________________________________________________________

INTRODUCTION

New Zealand is an ethnically diverse society and is set to become more so, with record levels of net migration in the past five years.

In Census 2013, the major ethnic groups in New Zealand were European (74 per cent); Māori (14.9 per cent); Asian (11.8 per cent); Pacific (7.4 per cent); and Middle Eastern/Latin American/African – also abbreviated as MELAA (1.2 per cent)1.

Multicultural populations require a healthcare system that provides culturally safe care. Culture and language barriers have a big impact on health outcomes for patients from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds. Understanding the patient’s experiences, identifying their challenges and implementing strategies to help solve these challenges ensures that patients receive culturally safe nursing care, disparity is reduced and good health outcomes are achieved.

LOCAL CASE STUDIES

This article draws on the authors’ own case study research, which is aimed at helping nurses understand the in-patient experiences of patients belonging to CALD groups in New Zealand and identifying strategies to support patients and their families during their hospital stay. The case studies involved patients from CALD backgrounds who received care at the coronary care unit of a district health board hospital between April and May 2018.

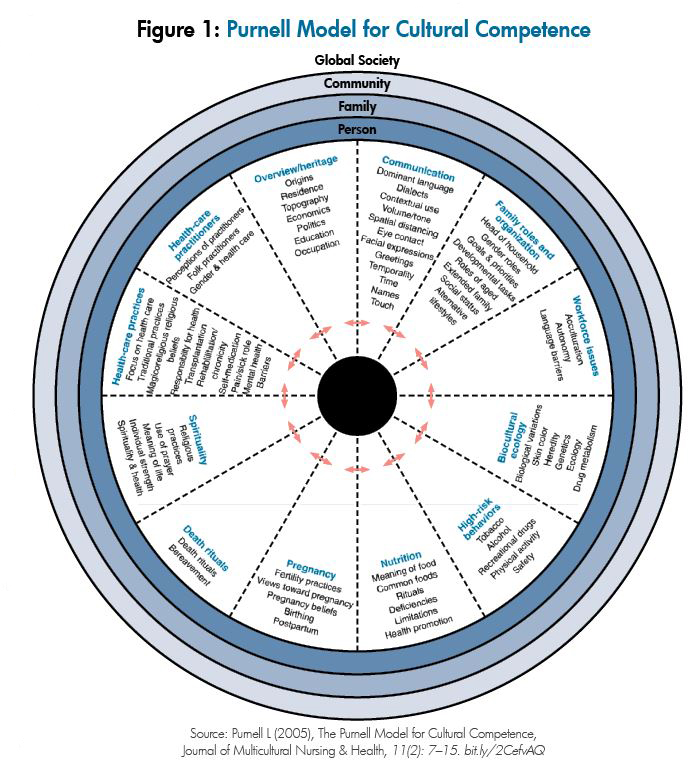

Three themes emerged from interviewing the coronary care patients using Purnell’s Model of Cultural Competence (see Figure 1). These are: the importance of family; views about illness and its impact on their lives; and barriers in accessing healthcare services.

The importance of family

Patients from collective cultures value family involvement and engagement in their care. The first theme that emerged from the interviews was the importance of family support in the care of a sick family member.

“Children and grandchildren look after the loved ones.”

Mr VM, 67, ventricular fibrillation arrest, Tongan.

“To look after the elder, it is important.”

Son of Mrs VN, 80, end-stage IHD, Indian.

Looking after family members was central to the patients interviewed, who were from Tongan, Samoan, Indian and Serbian backgrounds.

“It is better for us to look after the sick at home so they don’t feel lonely in the hospital.”

Mr VM, 67, VF arrest, Tongan.

“Always stay with the sick. We look after the sick.”

Son of Mrs VN, 80, end-stage IHD, Indian.

Extended family also play an important role in looking after sick family members.

It [extended family] is important. Grandkids look after their grandparents.”

Mr O, 60, NSTEMI, Samoan.

Family support is important in providing patients from CALD groups with physical and emotional support while in hospital2.

Views about the illness and its impact on their lives

Cultures have different ways of understanding illness and may attribute different causes to the origin of their symptoms. How illness is explained is strongly influenced by families’ cultural and religious backgrounds. Patients’ views about disease causation and how it impacts on their lives vary.

One patient attributed his illness to a higher power.

“It [illness] is a way God

teaches you sometimes in life;

a wake-up [call] from God”

Mr VM, 67, VF arrest, Tongan.

Whereas another attributed it to lifestyle.

“The first reason is smoke. Then after 15 years, illness comes. Second is food; I eat anything.”

Mr S, 60, STEMI – PCI to LAD, Serbian.

“Keep rules, restrict – no fats,

stop smoking, exercise.”

Mr S, 60, STEMI – PCI to LAD, Serbian.

Some of the patients displayed feelings of contentment even when they were sick.

“I’m better, I’m happy.

Everything is in my hands now.”

Mr S, 60, STEMI – PCI to LAD, Serbian.

BARRIERS TO ACCESSING HEALTHCARE SERVICES

Patients’ views and explanations of their illnesses affect the way they respond to and manage them. In addition to the wider systemic barriers, language and cultural issues are the two most widely experienced barriers to service utilisation3, 4.

Patients identified several barriers in accessing healthcare services. Migrants from CALD backgrounds may be unfamiliar with New Zealand health services and how to access them. One patient saw the need for advertising healthcare services to the Samoan community.

“Some people do not know how to access health care. Public should be aware what services are available. Broadcast services.”

Mr O, 60, NSTEMI, Samoan.

Another patient identified language as a barrier and also the concerns that patients may have about their privacy and confidentiality when interpreters are used.

“The difficulty is the language barrier. The problem with the translator is that she will not say the same thing to the translator that she will say to me.”

Son of Mrs VN, 80, end-stage IHD, Indian.

Patient insights in the interviews about barriers to accessing healthcare services highlight a number of areas for improvement. The first is the need for translated information in relevant languages delivered through ethnic media, such as radio stations and newspapers. Targeted and tailored health education needs to be available to ethnic communities.

The second is patient’s concerns about their maintaining privacy and confidentiality when professional interpreters are used. Confidentiality becomes an issue, particularly in smaller communities. Patients may be reluctant to use an interpreter because they know the interpreter or have fears that their medical information will be made public. At the beginning of a consultation, it is important to reassure the patient and their family that the health practitioner and the interpreter will respect the patient’s rights to confidentiality.

HEALTH CARE CHALLENGES AMONG CALD GROUPS

Patients from CALD groups may face psychological stress, treatment barriers, language barriers, challenges with informed consent, and the risk of adverse events when there are communication difficulties.

Psychological stress

The stresses that CALD patients experience are not just physical in nature but also psychological5. For any patient, illness can be a major stressor, but for patients from CALD backgrounds, the stress may be exacerbated by communication difficulties.

In particular, patients with limited or no English language experience anxiety and powerlessness because of their inability to communicate with health practitioners2.

Even with the use of interpreters, the patient may feel stressed as they may not feel fully understood. Moreover, the problem with communication causes stress not only to patients but also to healthcare providers6. For this reason, knowing how to work with interpreters – including how to pre-brief and debrief when using an interpreter for a consultation – is an important skill for health practitioners to gain.

Treatment barriers

Besides the psychological stress that the patients may experience while in the hospital, they may also encounter treatment challenges.

A CALD patient is more likely to refuse treatment7. Treatment refusal may be due to the patient’s inability to understand their illness and the treatment offered2, 8. Treatment refusal can lead to non-adherence with prescribed treatment plans, longer hospital stays and increased risks of readmission compared with English-speaking patients9. Communication problems also lead to treatment delays10.

Patients who have limited or no English language require an interpreter before they can make decisions regarding treatment. This may delay treatment, including procedures where the patient is required to follow instructions, such as X-rays and surgical procedures. Successful treatment requires good communication between the health practitioner, the patient and their family5, 11.

Language barrier

Good cross-cultural communication is important for health practitioners and patients to understand each other. Health practitioners need to assess, for example, whether patients are using traditional remedies or herbal medicines. Patients need to understand their illness and the treatment being offered. In acute care settings, health practitioners must utilise professional interpreters, where needed, to help them communicate effectively.

However, some studies prove that errors in transmitting information still occur even with the utilisation of professional interpreters12. This often occurs when the health practitioner is not trained in how to work with an interpreter and is not in control of the interpreting session.

Underutilisation of interpreters has also been reported in the literature13. It is sometimes easier to not utilise interpreters for patients who can speak basic English. However, this may lead to major impacts on the patient’s health outcome14. Sometimes bilingual staff are accessed as interpreters; however, because of the lack of professional training, errors such as omissions, addition, substitution and condensation of information occur8.

Patients who require interpreters have problems with taking in and remembering information15. It is therefore important to ensure that patients get adequate support from the healthcare team to ensure that correct and adequate information is provided for successful care and discharge.

Challenges with informed consent

Communication is also important when patients provide informed consent. Since informed consent is legal in nature10, patients should understand what they are consenting to. The transfer of information should be clear and accurate.

When medical information regarding a necessary procedure is given to a patient, it is critical for informed consent that they understand and agree to what the health practitioner is communicating to them. It is difficult enough at times to obtain informed consent from an English-speaking patient, but it is much more so from those who speak no or limited English.

In such cases, interpreters play an essential role. Regardless of the language spoken, informed consent is a patient’s right and healthcare providers need to ensure that this process is managed competently and professionally.

Adverse events

CALD patients are at risk of adverse events when there is a language barrier between themselves and the health professional. Diagnostic and medication errors are examples of adverse events9, 16, 17. Non-English-speaking patients may struggle to understand medical terms in English18, which may directly affect the quality of services they receive and their timely access to services18, 19. These patients are disadvantaged in accessing health services equitably with other groups due to the cultural and linguistic barriers discussed8. Healthcare practitioners can improve the quality of care that CALD groups receive by gaining the knowledge, attitudes and skills needed to become culturally competent.

STRATEGIES TO REDUCE THE HEALTHCARE CHALLENGES

There are ways to help reduce the challenges faced by minority ethnic groups in health care. These include promoting and practising cultural competence and safety among healthcare providers, using professional interpreters, and encouraging family support.

Providing culturally competent care

Cultural competence can be defined as developing an awareness of one’s own existence, sensations, thoughts and environment without letting it have an undue influence on those from other backgrounds; demonstrating knowledge and understanding of the client’s culture; accepting and respecting cultural differences; adapting care to be congruent with the client’s culture (Purnell, 1998)20.

Providing culturally competent care is a way to reduce barriers to accessing healthcare services for CALD patients18. Practitioners’ abilities to engage patients and their families and to assess and understand their explanatory models of health and illness will contribute to good health outcomes for the patients6, 16, 21.

Developing cultural competence

Campinha-Bacote and Munoz (2001)22 proposed a five-component model for developing cultural competence, which is outlined as follows:

- Cultural awareness involves self-examination of in-depth exploration of one’s cultural and professional background. This component begins with insight into one’s cultural healthcare beliefs and values. A cultural awareness assessment tool can be used to assess a person’s level of cultural awareness.

- Cultural knowledge involves seeking and obtaining an information base on different cultural and ethnic groups. This component is expanded by accessing information offered through sources such as journal articles, seminars, textbooks, internet resources, workshop presentations and university courses.

- Cultural skill involves the nurse’s ability to collect relevant cultural data regarding the patient’s presenting problem and accurately perform a culturally specific assessment. The Giger and Davidhizar model23 offers a framework for assessing cultural differences in patients.

- Cultural encounter is defined as the process that encourages nurses to directly engage in cross-cultural interactions with patients from culturally diverse backgrounds. Nurses increase cultural competence by directly interacting with patients from different cultural backgrounds. This is an ongoing process; developing cultural competence is a journey.

- Cultural desire refers to the motivation to become culturally aware and to seek cultural encounters. This component involves the willingness to be open to others, to accept and respect cultural differences, and to be willing to learn from others.

The disparities that arise due to cultural factors make cultural competence a priority in health care24. But there is no simple formula for solving cultural issues and establishing plans in delivering culturally competent nursing care. When challenging cultural issues arise, nurses might like to discuss and consult with senior colleagues and management to ensure that such issues can be resolved in the best interest of the patient.

Using trained interpreters

Using trained interpreters, rather than family members or bilingual staff, is important10 as it ensures that correct information is being relayed to patients, reduces the risk of errors and leads to improved health outcomes16. The importance of using trained health professionals to ensure good cross-cultural communication and safe, effective care for non-English-speaking patients is also highlighted in this article.

Extended family provides support

“To look after the elder, it is important.”

Son of Mrs VN, 80, end-stage IHD, Indian.

It is important to recognise the role of extended family in the care and support of the sick in collective cultures18. Knowing how to engage with family members, to work with the decision-makers and to communicate respectfully is an essential part of building trust and rapport.

The family will expect to be engaged and consulted and will play a significant role in decision-making for those who are sick2. Family members may advocate for the sick member, facilitate communication among healthcare providers, as well as provide basic care2. They may also communicate the sick member’s fears, needs and feelings to the health practitioner2. Encouraging family support in the care of patients from CALD groups is recommended.

Patients’ and families’ cultural and religious beliefs and practices should also be included in treatment regimes where practicable and safe16.

CONCLUSION

Providing culturally competent and safe care to all patients is an essential nursing responsibility. Due to the growing number of patients from CALD groups – and the challenges and barriers they experience in the healthcare setting – it is important for nurses to practice cultural competence, to use professional interpreters, and to encourage family support. It is essential for nurses to reflect on the experiences of their cross-cultural interactions with patients and their families’ experiences, as well as the cultural knowledge and skills needed to ensure that quality care can be provided for CALD patients at all times.

View the PDF of this learning activity here >>

___________________________________________________________

About the authors:

- Krinessa Valenzuela, RN, BSciNsg, PGDip gained her nursing degree at the University of the Philippines and currently works in the coronary care unit of Hutt Hospital HVDHB while studying for her Master of Nursing.

- Monina Hernandez, RN, BSN, MNur (Hons) is a lecturer at the School of Nursing, Massey University.

This article was peer reviewed by:

- Annette Mortensen, RN, PGDipEd, MPhil (Nursing), PhD, project manager research and development for eCALD services at Waitemata DHB.

- Jenny Song, RN, BN (Wintec), PGDip (Nursing), Bachelor of Medicine (Xuzhou),

a senior academic staff member at Wintec’s Centre for Health and Social Practice.

RECOMMENDED RESOURCES:

- eCALD: the Ministry of Health-funded eCALD service provides free, accredited e-learning courses for health professionals working with culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) groups in New Zealand, including working with interpreters: www.ecald.com/courses/cald-cultural-competency-courses-for-working-with-patients.

- Cultural awareness assessment tool: a simple, 17-question tool for gauging a nurse’s cultural awareness from Catalano’s Nursing Now: Today’s Issues, Tomorrow’s Trends. Available online at bit.ly/2oUDQC1.

- Cultural assessment model: key components of the Giger and Davidhizar cultural assessment model23 for assessing cultural differences in patients can be viewed at bit.ly/2O3rzGn.

- Working with interpreters for primary care practitioners: an e-learning module developed by the University of Otago: https://www.otago.ac.nz/wellington/e-learning/arch/story_html5.html

Nursing Council definition of cultural safety:

The effective nursing practice of a person or family from another culture, and is determined by that person or family. Culture includes, but is not restricted to, age or generation; gender; sexual orientation; occupation and socioeconomic status; ethnic origin or migrant experience; religious or spiritual belief; and disability.

The nurse delivering the nursing service will have undertaken a process of reflection on his or her own cultural identity and will recognise the impact that his or her personal culture has on his or her professional practice. Unsafe cultural practice comprises any action which diminishes, demeans or disempowers the cultural identity and well being of an individual.

References

- STAT NZ (2013). 2013 Census quick stats bout culture and identity. Retrieved July 2018 http://archive.stats.govt.nz/Census/2013-census/profile-and-summary-reports/quickstats-culture-identity/ethnic-groups-NZ.aspx

- GARRETT P, DICKSON H & WHELAN A (2008). What do non-English-speaking patients value in acute care? Cultural competency from the patient’s perspective: A qualitative study. Ethnicity & Health13(5) 479-496.

- MEHTA S (2012). Health Needs Assessment of Asian People Living in the Auckland region. Auckland: Northern DHB Support Agency. Retrieved from: https://www.countiesmanukau.health.nz/assets/About-CMH/Performance-and-planning/health-status/2012-health-needs-of-asian-people.pdf

- STATISTICS NEW ZEALAND AND MINISTRY OF PACIFIC ISLAND AFFAIRS (2011). Health and Pacific peoples in New Zealand.Wellington: Statistics New Zealand and Ministry of Pacific Island Affair. Retrieved from: http://archive.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/people_and_communities/pacific_peoples/pacific-progress-health.aspx

- LEE T, SULLIVAN G & LANSBURY G (2006). Physiotherapists’ communication strategies with clients from culturally diverse backgrounds. Advances in Physiotherapy8(4) 168-174.

- COLEMAN J & ANGOSTA A (2016). The lived experiences of acute-care bedside registered nurses caring for patients and their families with limited English proficiency: A silent shift. Journal of Clinical Nursing26 678–689.

- NELSON A (2002). Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Journal of the National Medical Association 94(8) 666-668.

- HEANEY C & MOREHAM S (2002). Use of interpreter services in a metropolitan healthcare system. Australian health review: A publication of the Australian hospital association25(3) 38-45.

- WU M & RAWAL S (2017). ‘It’s the difference between life and death’: The views of professional medical interpreters on their role in the delivery of safe care to patients with limited English proficiency. Plos One(10) doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0185659.

- GARLOCK A (2016). Professional interpretation services in health care. Radiologic Technology88(2) 201-204.

- VAN ROSSE F, DE BRUIJNE M, SUURMOND J, ESSINK-BOT M et al (2016). Language barriers and patient safety risks in hospital care: A mixed methods study. International Journal of Nursing Studies 54 45-53.

- FLORES G (2005). The Impact of medical interpreter services on the quality of healthcare: A systematic review. Medical Care Research and Review 62(3) 255-299.

- SEERS K, COOK L, ABEL G, SCHLUTER P et al (2013). Is it time to talk? Interpreter services use in general practice within Canterbury. Journal of Primary Health Care 5(2) 129.

- ISAAC K (2001). What about linguistic diversity? A different look at multicultural health care. Communication Disorders Quarterly 22(2)110-113.

- LIPSON-SMITH R, HYATT A, MURRAY A, BUTOW P et al (2018). Measuring recall of medical information in non-English-speaking people with cancer: A methodology. Health Expectations21(1) 288-299.

- DAVIES S, DODD K & HILL K (2017). Does cultural and linguistic diversity affect health-related outcomes for people with stroke at discharge from hospital? Disability & Rehabilitation39(9) 736-745.

- SCHYVE P (2007). Language differences as a barrier to quality and safety in health care: The joint commission perspective.Journal of General Internal Medicine22(2) 360–361.

- TRUONG M, GIBBS L, PARADIES Y & PRIEST N (2017). “Just treat everybody with respect”: Health service providers’ perspectives on the role of cultural competence in community health service provision. ABNF Journal28(2) 34-43.

- THOMPSON D (2002). Cultural aspects of adjustment to coronary heart disease in Chinese-Australians: A review of the literature. Journal of Advanced Nursing39(4) 391-399.

- PURNELL L (2013). Transcultural Health Care: A Culturally Competent Approach. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company

- BRACH C & FRASER I (2000). Can cultural competency reduce racial and ethnic health disparities? A review and conceptual model. Medical Care Research and Review57(14)181-217.

- CAMPINHA-BACOTE J & MUNOZ C (2001). A guiding framework for delivering culturally competent services in case management. The Case Manager, 12(2), 48-5.

- GIGER J & DAVIDHIZAR R (2002). The Giger and Davidhizar transcultural assessment model. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 13, (2) 185-188.

- CAMPINHA-BACOTE J (2002). The Process of Cultural Competence in the Delivery of Healthcare Services: A Model of Care. Journal of Transcultural Nursing13 (3) 181–184.

In fact the scope is often undervalued, misunderstood and probably underestimated in terms of the flexibility it offers the New Zealand nursing workforce.

This is particularly so for those nurses who are working, or considering working, in non-traditional settings in non-traditional ways, for example self-employed nurses.

In many countries, nurses who become self-employed can struggle to retain their regulatory equivalent of an annual practising certificate, even if they are delivering clinical practice. Not so in New Zealand. Despite this, self-employed nurses still make up only a tiny percentage of the total nursing workforce; however the number is slowly and steadily rising.

Self-employment in nursing is still relatively unusual, but there are examples from New Zealand, particularly from the 1980s onwards, where entrepreneurial nurses saw an opportunity to deliver a clinically based service and took it, in areas like occupational health and nurse-led primary care services.

Today, nurses are self-employed not only in clinical practice, but also increasingly in non-clinical ‘consultant’ roles working locally, regionally, nationally or even internationally. These nurses are often in management, quality, policy or professional advice roles, where nursing knowledge and experience is vital, alongside project management and leadership skills.

Resources for self-employment

The steady growth in self-employed nurses has been recognised by the College of Nurses Aotearoa which has created a suite of web-based resources to support nurses considering self-employment as a future career option.

Planning a new business can feel daunting, especially for registered nurses and nurse practitioners as – unlike midwifery, physiotherapy or general practice – the New Zealand nursing profession does not have a strong history of self-employment.

For nurses considering solo self-employment or becoming an employer – either as a clinical or non-clinical business – there are now links in the resource kit to support them at each stage, from set-up to self-care, as well as how to maintain an income and professional nursing registration. The resource has six sections containing helpful advice, direction, prompts and links.

- Planning: first steps

Nurses who successfully set up and run businesses usually have a niche, or a specific skill set on which they draw and which will attract clients. Nurses new to this environment need to be sure about their abilities and that they have the professional networks, skill set, infrastructure, capital and qualifications to be offering and charging for the service they plan to deliver. They also need to make decisions about how to position the business, to check the markets and to assess how to find work.

2. Set up: business structure, marketing and tools for business

Businesses come in many shapes and sizes, but there are some fundamental similarities. These include needing a memorable name, registering the company, filing an annual return and deciding on business structure, website and email hosting, as well as managing contracts.

3. Finance: Invoicing and tax

Finance, invoicing and tax considerations are often the steepest learning curve for people new to running a business. They are often experts in the actual work, but not many nurses have had previous experience in calculating GST, dealing with the IRD or sending monthly invoices.

4. Security: insurance, indemnity and privacy

Security and business insurance is not something nurses need to consider as employees, however if they become employers or solo self-employed then these become vital. If delivering a clinical service, nurses need to be sure they are meeting the principles of the Nursing Council’s Code of Conduct and keeping records according to the Privacy Act. Those delivering a clinical service also need to consider public liability insurance.

All nurses should have professional indemnity as this is financially vital if any complaints are made in relation to their practice. Self-employed nurses should also consider insurance for the business, in case they become unwell or unable to trade for any period of time.

5. Nursing regulatory requirements

Registered nurses who move into self-employment in non-clinical roles will often ask if they need to maintain an annual practising certificate (APC) from the Nursing Council of New Zealand:

- Registered nurses undertaking any clinical practice, delivering clinical care must complete the clinical competencies.

- Registered nurses who practise in direct client care AND management or education or policy or research must meet both sets of competencies.

- If only in non-clinical practice then check for the correct registered nurse competencies – either management or education or policy or research.

- The correct competencies and assessment forms are on the Nursing Council website.

- Nurse Practitioners have one set of competencies¹⁵, also available on the Council’s website.

6. Self-care

Research shows that people running their own businesses often forget to look after themselves.

Examples range from never taking holidays and working longer and longer hours to feeling huge responsibility for sustaining an income.

Another vital component of nursing self-employment is keeping professionally connected. This can be through professional nursing organisations, such as the College of Nurses, or making time to attend conferences and nursing events.

Isolation can be a big factor for the self-employed; there is a need to connect with others in similar roles. How self-employed nurses achieve that connection can be varied, but it is important, especially if working from home, to remember to link back up to colleagues and support.

Conclusion

Self-employment can certainly be rewarding, but it doesn’t suit everyone and for most who take that pathway, it means learning a whole new set of skills.

So, before considering setting up any sort of business providing a nursing service – either clinical or non-clinical – it is important to do your homework and consider the niche into which you may fit.

- Do you have the qualifications or experience?

- Do you have somewhere to work?

- Is there a market?

- What is your risk?

- Do you have the ability to manage a potentially precarious income and the day-to-day management of your own business, as well as offering a quality service?

If you need more information, check out the self-employment resources on the College of Nurses website www.nurse.org.nz.

The resource has links to the College’s professional supervisor’s page but for specific enquiries about setting up a business in nursing you can contact the College office on [email protected].

Author: Liz Manning RN, MPhil, FCNA(NZ), is director and owner of Kynance Consulting, where she works as a self-employed nurse consultant and is currently undertaking a PhD research study on self-employed, non-clinical registered nurses in New Zealand.

References

- Nursing Council of New Zealand. (2007). Competencies for Registered Nurses. Retrieved from Wellington:

- International Council of Nurses. (2004). Guidelines on the Nurse Entre/Intrapreneur Providing Nursing Service. Retrieved from Geneva, Switzerland

- Stahlke Wall, S. (2017). The impact of regulatory persepctives and practices on professional innovation in nursing. Nursing Inquiry, 1-8. doi:10.111/nin.12212

- Wall, S. (2015). Dimensions of Precariousness in an Emerging Sector of Self-Employment: A study of Self -Employed Nurses. Gender, Work and Organisation, 22(3), 221-236.

- Wilson, A., Whitaker, N., & Whitford, D. (2012). Rising to the Challenge of Health Care Reform with Entrepreneurial and Intrapreneurial Nursing Initiatives. The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 17(2). doi:10.3912/OJIN.Vol17No02Man05

- Nursing Council of New Zealand. (2010). The New Zealand Nursing Workforce: A Profile of Nurse Practitioners, Registered Nurses and Enrolled Nurses 2010. Retrieved from Wellington http://www.nursingcouncil.org.nz/Publications/Reports-and-workforce-statistics

- Nursing Council of New Zealand. (2011). The New Zealand Nursing Workforce: A profile of Nurse Practitioners, Registered Nurses and Enrolled Nurses 2011. Retrieved from Wellington: http://www.nursingcouncil.org.nz/Publications/Reports-and-workforce-statistics

- Nursing Council of New Zealand. (2013). The New Zealand Nursing Workforce: A Profile of Nurse Practitioners, Registered Nurses and Enrolled Nurses 2012-2013. Retrieved from Wellington: http://www.nursingcouncil.org.nz/Publications/Reports-and-workforce-statistics

- Nursing Council of New Zealand. (2015). The New Zealand Nursing Workforce: A profile of Nurse Practitioners, Registered Nurses and Enrolled Nurses 2014-2015. Retrieved from Wellington: http://www.nursingcouncil.org.nz/Publications/Reports-and-workforce-statistics

- Hawken, L., & Tolladay, J. (1985). Short-term autonomous nursing in a small community. Palmerston North: Massey University.

- MacDonald, J. (1989). Two Independent Nursing Practices: An Evaluation of a Primary Health Care Initiative(T. Scotney Ed.). Wellington: Department of Health.

- Nevatt, E. A. (1989). Occupational Health Care: An Entrepreneurial Venture in New Zealand. Palmerston North: Nevatt, E A.

- Nursing Council of New Zealand. (2012). Code of Conduct. Retrieved from Wellington: http://www.nursingcouncil.org.nz/Nurses/Code-of-Conduct

- Privacy Act (1993)

- Nursing Council of New Zealand. (2017). Competencies for the nurse practitioner scope of practice. Retrieved from Wellington: http://www.nursingcouncil.org.nz/Nurses/Scopes-of-practice/Nurse-practitioner

- Mason, C. M., Carter, S., & Tagg, S. (2011). Invisible businesses: The characteristics of home-based businesses in the United Kingdom. Regional Studies, 45(5), 625-639.

- Sankelo, M., & Åkerblad, L. (2009). Nurse entrepreneurs’ well-being at work and associated factors. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 18, 3190-3199. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02666x

This followed the censuring last year of another nurse who, in a rush, mixed up one of the vaccines for a 15-month-old after she couldn’t find the yellow card (the Ministry of Health’s National Immunisation Schedule reference card) that spells out which vaccines to deliver at each age milestone.

Neither child was harmed, but sadly, in Samoa, two nurses are awaiting trial after the tragic deaths of two infants following MMR vaccinations. The cause of the deaths is still unknown, but Samoa’s use of multi-dose vials of the MMR vaccine raises questions over dilution errors.1

New Zealand uses the single-dose MMR vaccine with the diluent provided in a prefilled syringe in the same package. This minimises the risk of dilution errors, but other minor errors remain a risk – the same as in any medication administration environment. This is particularly the case for busy practice nurses juggling elderly patient phone calls, GP requests to squeeze in patients’ blood tests or wound dressings, plus waiting rooms of stressed mums with restless toddlers and crying babies.

New Zealand’s immunisation standards for vaccinators are provided in the appendix of the Immunisation Handbook 2017 to guide nurses and other vaccinators on competent deliveries of safe and effective immunisation services so a patient doesn’t receive the wrong vaccine at the wrong age or by the wrong route or at the wrong interval. The handbook also provides, in another appendix, specific instructions for the preparation (including the reconstitution) and the administration of vaccines.

Nursing Review talked to Immunisation Advisory Centre (IMAC) education coordinator Trish Wells-Morris and checked out Health Quality & Safety Commission advice for tips on safe vaccination and infection control for busy nurses.

Wells-Morris says New Zealand has access to very good quality vaccines that are supplied ready for use and delivered via pre-filled syringes. “So the opportunity for contamination or to make a mistake is minimised.”

When a very occasional vaccination error occurs, she says New Zealand’s open and voluntary approach to incident reporting means nurses will often ring IMAC’s 0800 IMMUNE number to discuss concerns and whether any further action is needed.

“Organisations have quality systems to follow up and investigate any incidents and it’s a non-punitive system that works best.”

These errors usually don’t cause harm; for example, a lack of documentation resulting in a child inadvertently receiving the same vaccine twice. “So the nurse is concerned about any harm to the baby… that the baby has had an extra vaccine and will they suffer… fortunately, babies are very resilient.”

But it’s a given that no nurse wants to cause anxiety or the risk of harm to a patient through avoidable human error.

Don’t shortcut pre-vaccination checks

Following a clear pre-vaccination check list, including gaining informed consent, helps to ensure the right vaccines are given to the right child or adult.

But a rushed nurse – working with a mother distracted by tired and fractious children – can miss a check and risk an error happening.

“Take a few breaths, slow down, and follow the process,” recommends Wells-Morris. “The potential for error increases if corners are cut.” This is particularly the case when everybody is busy, children are crying and a hard-working practice nurse is under pressure.

The pre-vaccination check includes not only screening to check there is no reason why the vaccine/s shouldn’t be given that day but also which vaccine the child or adult is due to have and what their current vaccination status is.

In the case of a child, Wells-Morris says that may involve checking firstly their Well Child record; secondly the practice’s electronic patient management system record; and thirdly, the National Immunisation Register.

Checking is particularly important if the family are new or infrequent visitors to the practice and they may have had an opportunistic vaccination at another practice by an outreach nurse or during a hospital visit. With no national register for adults, nurses must rely on patient recall.

When the vaccines are taken out of the vaccine fridge, the vaccine expiry date is checked and the nurse visually checks the vials for any contaminants; for example, if anything has broken off the rubber seal that could be drawn up into the syringe.

Wells-Morris says ideally at this point the vaccinator would check the selected vaccines with another vaccinator using the yellow card to ensure that they are the correct vaccines for the child in question.

In the two recent Health & Disability Commission complaints mentioned in the opening paragraphs, the vaccinating nurses’ errors were not picked up. In one case, they had mislaid the card and failed to correctly inform the checking nurse of the child’s age. In the other case, the checking nurse was told the 12-year-old girl was having her 11-year-old Boostrix vaccine rather than the requested Gardasil.

The HDC’s expert nurse advisor in the Gardasil case suggested that the vaccine check should have been done in the same room as the patient and, if working alone, a nurse could use the caregiver or patient to confirm the vaccine. Wells-Morris agrees that, in the right circumstances, nurses may wish to ask a parent or caregiver to check the vaccines against the Ministry’s yellow card.

Gaining informed consent from the caregiver or adult to each vaccine administered is also another safeguard.

Once the right vaccine is consented and confirmed, the nurse draws up and mixes the vaccine and administers it as directed on the vaccine’s data sheet. They then document the vaccine details, including on the National Immunisation Register and Well Child book if vaccinating a child, to complete the records.

Common vaccine errors and causes

- Wrong vaccine: often because they have similar names or cover the same diseases i.e. Infanrix.

- Wrong interval between doses: the immunisation history is not up to date.

- Wrong age: usually involves vaccines with age restrictions or different vaccines targeted at different age groups.

- Wrong injection site or route: an intramuscular vaccine given in site without enough muscle, or MMR given intramuscularly rather than subcutaneously.

- Wrong patient: multiple siblings turning up at the same time to a busy clinic for vaccinations.

- Incorrectly prepared vaccines: multiple component vaccines where an extra component, e.g. Hib, is not added or only the diluent is administered.

- Expired vaccine used: nurse forgot to check or the expiry date is unreadable.

- Cold chain failures: failure to keep vaccines at 2–8 degrees C at all times.

Tips for avoiding vaccine errors

- Store vaccines appropriately in a pharmaceutical refrigerator to reduce risk of child/adult vaccine formulations or vaccines with similar names being confused.

- Always confirm which vaccine the adult or child has presented for.

- Check their vaccination status via health records and, if a child, via the National

- Immunisation Register to avoid double-up errors and ensure correct interval between vaccine doses.

- When administering two component vaccines like DTaP-IPV-HepB/HiB (Infanrix hexa), document both vials’ details before vaccinating to reduce risk of missing HiB.

- Get a colleague to check you have the correct vaccines for the correct child using the Ministry of Health’s immunisation schedule yellow card guide.

- Involve the parent or patient in verifying you are administering the right vaccine, as well as getting informed consent.

- If more than one child from the same family is being seen, only bring one child’s vaccines into the room at a time.

- Check the child’s identity by using both name and birth date prior to administering each vaccine.

- Promptly document the details of vaccines given in the health record and, if a child, in the National Immunisation Register so the vaccination status is updated for future vaccinators.

Sources: Health Quality & Safety Commission, Medication Safety Watch, October 2015

FURTHER RESOURCES:

- Immunisation Advisory Centre’s vaccine administration overview: www.immune.org.nz/health-professionals/vaccine-administration-overview

- Ministry of Health Immunisation Handbook 2017: includes the Immunisation Standards for Vaccinators: www.health.govt.nz/publication/immunisation-handbook-2017

- Vaccination video guides: IMAC has vaccination guide videos available on its community pharmacist advice page: www.immune.org.nz/pharmacists

- Cold chain guidelines: www.health.govt.nz/publication/national-standards-vaccine-storage-and-transportation-immunisation-providers-2017

-

The WHO-approved MMR vaccine used in Samoa is delivered in multidose vials containing five doses, and vaccines from the same batch have been used safely around the world. (The only multidose vial vaccine used in New Zealand is the BCG vaccine, which is only administered by specially trained vaccinators.) Samoa’s Commission of Inquiry into the deaths of two infants who died after being administered the MMR vaccine in July was adjourned in September until after the court case of the two nurses charged with manslaughter is heard early next year. The cause of the deaths is still unknown, but there have been calls in Samoa for ongoing nurse training, with indications that human error may have been involved in the dilution of the multidose vaccine.

]]>

That’s wound care nurse specialist Liz Milner’s first rule of thumb on her ‘hobbyhorse’ of wound swabbing. And if a swab is called for, do it properly, otherwise the results may be of little use.

Milner says people often appear to take wound swabs for the sake of it. If they don’t do it right – or for the right reason – the laboratory results are likely to come back showing a predictable ‘mixed skin flora’ result.

“But if there’s no clinical markers of infection then we’re not going to treat,” says Milner, “because a lot of the wounds, particularly of long duration, are going to have colonised bacteria, which we wouldn’t treat anyway.” (The common skin flora or bacteria colonising a wound are mostly harmless and won’t result in infection.)

But swabbing for the right reasons with the right technique can isolate the bacteria causing the infection and ensure that the patient is on the right antibiotic to treat it.

A wound swab can be helpful or necessary when the nurse observes the likely signs of an underlying infection impeding the healing process, such as redness, heat and swelling, an increase in pain, a malodorous wound and an increase in exudate.

Milner reminds nurses that patients with diabetes may not present with the classic infection symptoms so the threshold for swabbing should be lower.

“Some people with diabetes have a decreased arterial flow – so you may see a pale wound with minimal exudate, no change in pain levels (due to a sensory neuropathy) and no redness, heat or swelling. So just be mindful that the diabetic group is quite unique.”

Swabbing technique has zigged and zagged

Milner says that over the years wound swab advice has changed.

“Back in the day, we’d take a lab swab and the more pus we could get on it the better – it was quite exciting. We’d stick it in the tube and send it off to the lab.”

Then there was a shift to the ‘Z’ technique, in which swabs are passed over the wound surface – avoiding the wound margins – in a zigzag fashion.

More recently, the new ‘Levine’ technique was found to generate more useful bacterial results from the lab than the zigzag. The Levine technique involves applying slight pressure with the swab to take a sample from about one square centimetre of tissue at the centre of the lesion or in an area of the wound that appears infected.

But that was then, says Milner. Now, the evidence-based method seen as even better at detecting the most types of bacteria present across the whole wound surface is the ‘Essen Rotary’ method.

The Essen Rotary method involves taking the sample by moving the swab from the periphery toward the centre of the wound (covering the entire wound area) using a spiralling motion while applying slight pressure.

Doing it correctly

The first step before taking a wound swab is to cleanse the periwound and wound thoroughly so the swab sample can gather the bacteria in the wound bed and not the harmless skin flora or contamination from the previous primary dressing. For example, taking a swab on a wound that has an iodine base dressing will not provide an accurate result.

Milner advises not to clean the wound with an antiseptic, such as povidone-iodine, and instead use water or normal saline. If the wound bed is dry, pre-moisten the cotton-tipped swab to increase the chance of recovering organisms from the wound bed. Then combine the Essen Rotary swab technique with a gentle pressure that squeezes up bacteria from the deeper underlying structures.

Recent research has shown that this method is a quick and easy-to-use modification of conventional swabbing methods, such as the Levine technique and the Z technique. It involves only slightly more effort and offers significantly higher sensitivity in detecting superficial bacterial colonisation in chronic wounds like venous leg ulcers.

Once the swab is placed into the culturette tube and labelled, the next important step is to ensure the laboratory request form includes relevant information.

“It’s really important that you fill out on the lab form what antibiotics the person is on, whether you are using an antimicrobial dressing, and whether it’s iodine, silver, honey, etc,” says Milner.

She says the more information a nurse can give the lab the better – including the nature of the wound, whether it is acute or chronic and any chronic conditions or illnesses the patient has that may affect the healing process.

Providing the laboratory with accurate information will ensure a much better result, she says. Rather than receiving a result of ‘mixed skin flora’ after having ‘swabbed for swab’s sake’ the swab sample may aid the patient’s healing by ensuring they are on the right antibiotic for the right bacteria.

Consider wound swabbing when:

- there are clear clinical markers of infection like redness, heat, swelling or pain and the wound is malodorous and with an increase in exudate

- cellulitis is present

- antibiotic treatment is failing

- the wound is deteriorating, increasing in size or failing to heal

- the patient has high risk factors for MRSA.

- There is a lower threshold for swabbing wounds if the patient is very young, elderly, has a lowered immunity, diabetes or another chronic condition affecting circulation.

How to swab a wound:

- Clean the wound and periwound thoroughly with water and gauze.

- Swab the wound in a circular/spiral pattern moving from the wound periphery to the centre of the wound area (covering the entire wound area).

- Apply slight pressure while swabbing so fluid/bacteria is pushed up from below the wound surface.

- Label the swab sample and add relevant information to the lab request form, including type and history of wound, if the patient has a chronic condition and what systemic antibiotics or topical antimicrobials were being used.

The aim of reducing the harm of surgical site infections (SSIs) – and the estimated millions of wasted health dollars through readmissions – led to a targeted SSI monitoring and improvement programme, focusing first on hip and knee replacement surgery, being launched in 2012 in public hospitals across the country.

Because SSIs are the cause of nearly all the healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) in private elective surgical hospitals, the 10 Southern Cross hospitals began much earlier monitoring and reporting results on not one but 10 surgical procedure groupings. An increased focus on the problem saw the Southern Cross SSI rate start to fall and an active quality improvement programme started in 2010 saw the rate fell even further.

Recently published research in the New Zealand Medical Journal (NZMJ)1 shows that the Southern Cross campaign made a significant impact, with the number of patients experiencing an SSI within a month of their surgeries reducing from 3.5 per cent in 2004 down to 1.2 per cent in 2015.

Nurses, particularly the network’s infection prevention and control nurses, played a major role in introducing the interventions, monitoring changes in practice and collecting data on the nearly 43,000 patients whose surgeries were part of the study.

Rosaleen Robertson, Southern Cross Chief of Clinical Governance and a registered nurse, says it was a real team effort and not without its challenges – including getting everybody on board. “It is quite resource-intensive, but when you see the results it makes it all very rewarding.”

The two main evidence-based interventions of the programme introduced in 2010 were delivering pre-surgery prophylactic antibiotics more often at the right time and at the right dose, as well as encouraging a shift on the operating table to using alcohol-based surgical site skin preparation.

Also impacting on SSI rates was ongoing work on hand hygiene compliance, nurse-led pre-admission screening and education, raised awareness of the increased SSI risk for patients who are obese or have diabetes, plus good blood glucose and patient temperature control pre- and post-surgery.

Pre-admission challenges

A particular challenge for private surgical hospital nurses is the tight time frame they have to educate patients about the risks of infection, says Robertson. Most patients come into hospital almost immediately before their operations.

This makes the assessment by pre-admission nurses of the comprehensive patient health questionnaire even more important. The questionnaire is part of a patient’s pre-admission pack and is required to be sent in at least a week before their surgery so any patients with higher needs or greater risks of SSIs can be contacted as early as possible and, if needed, brought in for pre-admission consultations.

Southern Cross engaged with patients using a co-design method to improve how it communicated one piece of pre-admission advice: the request for patients not to remove hair from surgery sites.

“It’s really important that the patient avoids any method of removing hair themselves from their operation site before coming into surgery,” says Robertson. “Any breach of the skin caused by shaving – and they may only be micro-breaches of the skin – can provide an opportunity for pathogenic organisms to grow.”

She says the few patients that do so are generally trying to be helpful, but any hair removal should be left up to health professionals because of the heightened

SSI risk if patients do it themselves.

Although little can be done about some of the SSI risk factors in the usually short lead-up to elective surgery, patients can be educated about hair removal, hand hygiene, pre-op showering and hair washing, and advised that having their diabetes under good control and stopping smoking will help their surgical wounds heal faster.

Obesity, smoking and diabetes

The patients at greater risk of a surgical site infection include those who are obese, smoke, have higher surgical risk scores or have diabetes.

And while the Southern Cross statistics indicate the number of surgical patients who smoked decreased between 2004 and 2015, the numbers who were obese, had high surgical risk scores or had diabetes all increased. The proportion of surgeries on people with a body mass index (BMI) over 30 grew from 29 per cent to 36 per cent of

all surgeries.

The Southern Cross research confirmed the findings of Health Quality & Safety Commission’s public hospital SSI reduction programme, with both finding that obesity is a key SSI risk factor.

Dr Arthur Morris, a clinical microbiologist and lead author of the NZMJ’s Southern Cross article, says while the average SSI rate for orthopaedic surgery is about 1 per cent, if a patient is morbidly obese (a BMI of 40 or more), the infection risk may be four or five times higher. Morris is an infection control advisor to Southern Cross Hospitals and also clinical lead for the Commission’s public hospital SSI improvement programme.

He says for smokers, people with diabetes and the obese the common risk is poor vascular supply affecting their bodies’ abilities to fight any bacterial contamination of wounds. For the morbidly obese, in addition to the problems caused by restricted blood supply to the wound are issues like less mobility and how well the wound edges can adhere to each other.

With an obese person, it can be harder to get the skin edges on either side of the wound to be evenly matched, says Victoria Aliprantis, a registered nurse, who is Southern Cross’s Chief of Risk and Quality. She says that uneven wound edges can create gaps where the skin is not touching, which increases the chance that bacteria can enter the wound and cause infection.

Aliprantis says nurses need to be mindful of the risks and build it into their monitoring and care of wounds post-op. She says that if a wound is not closing particularly well then this should be escalated to the surgeon, but nurses can also use steri strips and other wound care dressings to pull the wound together and improve how the wound edges meet.

Antibiotics use: right time and right amount

For nurses to be as influential as they want to be in reducing SSIs, they need the time to be able perform their roles well, says Robertson.

This includes their important role in supporting the ‘sign-in’ and ‘time-out’ safety checklist procedure in the operating room that includes prompts over the timing of when prophylactic antibiotics are given.

Antibiotics timing is one of the key interventions in the SSI reduction strategy, with the aim of intravenous antibiotic cefazolin being given at the optimal time more often, to ensure enough antibiotic is in the tissue close to the surgery incision site before ‘knife to skin’, says Robertson. The optimal window of time is from one hour before surgery or, ideally, at least five minutes before ‘knife to skin’.

The study found that on-time antibiotic delivery improved from 72 per cent of the time in 2004 to 95 per cent by 2015 and the better timing had helped to reduce the SSI rate. Morris says in the last 10 minutes before ‘knife to skin’ there are many things going on and sometimes ensuring the patient is properly anaesthetised and is breathing properly overrides the timing of the antibiotic. Their new guidelines are now recommending that the antibiotic is given at least 10 minutes before ‘knife to skin’ to avoid it being missed before the focus shifts to critical procedures like intubation.

The right dose of antibiotic was another focus, says Morris, with a recommendation to use 2g or more of cefazolin for every patient to prevent the risk of the increasing number of obese patients receiving a dose that is too low.

Nurses ‘nudge’ shift to alcohol-based skin cleansing

In another of the major interventions – increasing the use of alcohol-based skin preparation – nurses are in key position to influence a surgeon’s choice.

The Southern Cross research confirmed that using an alcohol-based skin preparation can help reduce the SSI rate by almost 50 per cent and is ideal for most operations.

But some surgery areas and some surgeons have protocols that still favour using aqueous-based skin preparations.

Morris says some people are “a bit nervous” about using alcohol preparations as they are worried about a fire risk or a harm.

“Though if it is properly applied and left to dry, there is no risk or danger, but people have their preferences,” he says.

Aliprantis says there is a lot of ritual in theatre and it can be a challenge to ‘nudge’ people who have developed a preference for one method to change to another.

Robertson and Aliprantis say nurses are encouraged to be proactive in starting conversations and presenting the evidence to doctors to encourage them to consider change or to discuss it peer-to-peer with Dr Morris.

The research shows the use of alcohol-based skin preparation increased over the study period from 63 to 84 per cent, but a 2016 audit showed that there is still room for improvement as in 60 per cent of the time an aqueous skin preparation was used, an alcohol product should have been used instead.

Another area where it believes there is an opportunity to further reduce the SSI rate is targeting the most common bacteria causing SSIs – Staphylococcus aureus. A recent literature search for the Health Quality & Safety Commission (HQSC) showed using a proven ‘anti-staph bundle’, involving antiseptic nasal swabbing and antiseptic skin solutions to decolonise S. aureus from the skin and nose could reduce orthopaedic SSIs by about half.

“We are piloting [the bundle] in one of our hospitals that was part of the HQSC bundle collaborative,” says Muriel McIntyre, a registered nurse who is a Southern Cross Clinical Safety Quality Risk Coordinator.

“This is another initiative that is very much a collaborative process with nursing and doctors following through from pre-admission to admission services,” she says.

1. The full NZMJ research article can be read at https://bit.ly/2zKzlQP.

]]>Each year around 55,000 people get pressure injuries (PIs), once known as bedsores or pressure ulcers, ranging from an early-stage reddened patch over a pressure point, like a heel, to gaping wounds to the bone from which people can die.

Isitt and Nurse Maude district nurse Jade Lippiatt (pictured above), are two of the more than 50 nurses across the Canterbury and West Coast DHB regions who have successfully applied to become pressure injury prevention link nurses.

The new link nurse role is supported by a $6 million, three-year ACC campaign to reduce preventable PIs that kickstarted with Canterbury DHB last year and will see other regional initiatives rolled out nationwide.

It is part of the momentum that has built after years of lobbying by wound care nurses and the New Zealand Wound Care Society for PIs to be taken seriously at a national level. PIs are regarded as a quality marker of care because the risk rises when care rationing due to understaffing or lack of awareness results in patients not being moved in bed or having their skin assessed regularly enough.

This month the first quarterly reports on pressure injuries are being lodged with the Health Quality & Safety Commission by DHBs as a new joint strategy by the Commission, Ministry of Health and ACC steps up a notch.

The strategy follows a major 2015 report commissioned by KPMG on reducing PI harm, which estimated that about 3,000 of, the 55,000 people will have a PI wound so severe that muscles, bones or tendons may be exposed, requiring surgery to treat and repair the skin and tissue damage.

The DHB quality and safety marker reports will help to build the first solid, nationally consistent statistics on the scale of the problem and help to monitor the impacts of prevention strategies.

Link nurses

Julie Isitt has worked in orthopaedics for 16 years and says it is changes in the patients she cares for in the past five years that has increased her awareness of the risk of PIs.

An increasing number of older people are coming into hospital with complex co-morbidities like diabetes or dementia and less mobility, which has made her conscious of the need to turn and move patients at risk of PIs.

Jade Lippiatt first started working in older people’s health after graduating four years ago. After seeing the impact of PIs, she was motivated to become a link nurse to help stop these preventable injuries.

The aim of the Canterbury/West Coast initiative is to have 72 pressure injury prevention link nurses – one in every ward and aged residential care facility, plus one to two from each of the district nursing providers.

Susan Wood, a nurse and the Director of Quality and Patient Safety, Canterbury and West Coast DHBs, says the link nurse role is based on a UK concept to develop the skills of a network of nurses in a specialty area, in this case pressure injuries. And in turn, the link nurses can act as change agents in their own workplaces with an expectation they will drive PI quality improvement programmes in their workplaces.

The voluntary link nurses are expected to be at a proficient PDRP level and to have already completed an online PI prevention course. In return, they are funded to complete a three-day PI prevention and management paper at Ara Institute of Canterbury and meet once a month to network and support each other in their PI prevention work.

]]>Professor Gregor Coster, the review chair, said the colonoscopy workforce capacity remains a significant risk and is constraining the current NBSP roll-out.

In 2014 the National Nurse Endoscopy Advisory Group was established to develop and implement endoscopy nursing roles to help meet the expected workforce demands of the bowel screening programme.

Implementing the training programme to meet the demands for this new workforce, while being able to meet the targets set for the National Bowel Screening Programme, has not been without its challenges. Some of those we have faced and conquered, while some are still being addressed.

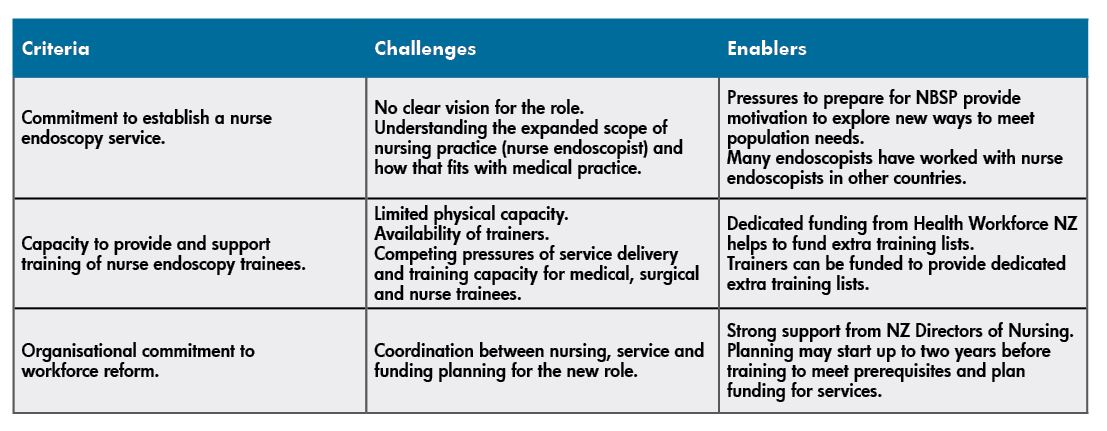

One of these challenges is that DHBs have to demonstrate a level of organisational readiness to be able to support nurses to complete the nurse endoscopy training and credentialing programme. The training programme needs not only nurses who have met the academic and clinical practice prerequisites but also the endorsement by DHBs of nurses performing endoscopies and a plan for the execution of the programme in accordance with the Nursing Council of New Zealand’s guidelines for the expanded practice for registered nurses.

The first priority for credentialed nurse endoscopists will be to provide routine endoscopies, which will free up experienced endoscopists to carry out bowel screening colonoscopies.

The criteria for determining DHB readiness are discussed in the table below, where we look at the particular challenges we have faced, and are still currently facing, in the ongoing delivery of the endoscopy training programme.

Delivery of the inaugural nurse endoscopy training programme got underway at the University of Auckland in 2016 as part of the Health Workforce New Zealand initiative to introduce the role of the nurse endoscopist.

The first cohort of four candidates has successfully completed the one-year academic programme (plus over 200 scopes each) and all have been accredited in at least one of the three scope modalities: gastroscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy. It takes at least two years of supervised training for any endoscopist trainee to reach competence, with the timing varying on their access to training lists and individual ability.

The challenges mentioned earlier meant there was no cohort in 2017, but a further four candidates started the academic programme this year and it is hoped to have four students in 2020. DHBs still have many questions about how to prepare for nurse endoscopists and part of our role has been to coach and support DHBs in introducing the new role.

Geographically, the students are from Auckland, Waikato and Otago, with five DHBs – Auckland, Counties Manukau, Waitemata, Waikato and Southland – currently engaged in the programme. There is growing interest from other DHBs, which is promising.

Nurse endoscopists have the potential to work across the continuum of care and this is already becoming evident, with two of the candidates from the inaugural course completing their prescribing pathway; one following the RN designated prescriber pathway and the other on the nurse practitioner pathway.

Collaborative curriculum

The University of Auckland developed the curriculum in collaboration with clinical experts to provide the theoretical and clinical skills component.

The academic component of the programme includes two postgraduate courses at master’s level completed in one academic year. To join the programme, nurses must have a clinical postgraduate diploma and a minimum of five years’ clinical experience post-registration. Three of those years are required to be in gastroenterology/endoscopy or a related specialty area such as colorectal surgery.

The endoscopy training programme focuses on the ongoing development of clinical expertise, using a practice development approach emphasising person-centred, evidence-based practice and critical thinking skills to improve health outcomes.

The clinical course coordinator of the endoscopy programme plays a crucial role, using knowledge of the sector to work with DHBs and clinicians to support trainees. Work-based training starts alongside the academic programme to allow the integration of increasing theoretical knowledge with practical skills.

Training continues until competence is achieved against an independent set of criteria aligned to national standards set by the Endoscopy Guidance Group of New Zealand (EGGNZ) for performing bowel screening colonoscopies. These standards apply to all endoscopists, whether they are medical practitioners or nurses.

The first priority for credentialed nurse endoscopists will be to provide routine endoscopies, which will free up experienced endoscopists to carry out bowel screening colonoscopies.

The academic/clinical partnership was critical when it came to working with the national steering group and setting the expectation that nurses provide both clinics and endoscopy lists to ensure holistic practice and the development of assessment and diagnostic skills.

The nurse endoscopy candidates are encouraged to spend time with areas aligned to the service to develop networks and gain a wider knowledge of pathology, radiology, surgery and multidisciplinary meetings. We have also worked with DHBs to develop standing orders as the sedation drugs commonly used during endoscopy are not currently on the list of drugs available to designated nurse prescribers. The support from anaesthetists in providing theoretical and simulation training has also been appreciated and is ongoing as we plan for changes at a national level to support this new role.

We have worked closely with DHBs and interested nurses to ensure they are ready before starting their journey. It has been a pleasure and a privilege to work with a wide range of people to overcome barriers when implementing this new role and delivering services to patients in a new way.

It is humbling to witness the personal and professional growth of students as they undertake the endoscopy training programme and lead the way for the future nursing workforce.

About the authors: Lesley Doughty RN MEd (Hons) (PG Programme Director) and Jacky Watkins RN MN (Course Coordinator) are professional teaching fellows at the University of Auckland and are responsible for developing and implementing the nurse endoscopy training programme.

]]>But regulation needs to be done well. Council decisions can have a cascading effect on public safety, nursing education, nursing practice, nursing registration and the everyday lives of 57,500 nurses. Developing good, sustainable regulatory policy is also resource and time hungry.

Looking back on her ten years in the top job Reed is not surprised that she feels tired sometimes.

“I look back and see what the team is achieved (over those ten years) and I think no wonder I’m tired and I’m sure other people are too.”

It’s been a big decade for nursing. Back in 2008 there were only 50 nurse practitioners – and not all of those NPs prescribed let alone registered nurses. Enrolled nurses were controversially called ‘nurse assistants’. The largest source of internationally qualified nurses (IQNs) was the UK not the Philippines and India as it is today. And uncertainty reigned over whether expanded nursing practice roles, like the first surgical assistant (FSA), fell in or outside the existing scope of practice for registered nurses.

The Nursing Council staff and governance board during Reed’s time has consulted, discussed and negotiated itself a path forward that met its mandate to ensure public safety and also helped meet the nursing profession and sector’s wish to evolve new nursing roles. Along the way it faced its fair share of criticism and resistance from those who thought the Council too strict or too liberal in its regulatory role.

The consensus amongst nursing leaders is that Reed did a darned good job in her dual role as CEO and registrar. The announcement of her resignation brought praise both personal and professional of her vision, her leadership, her approach and the resulting ‘right touch’ regulation which kept the public safe but still allowed the profession to be forward-focussed. The Council chair for the past three years, Catherine Byrne, is to step into Reed’s job in the New Year and says she wants to continue Reed’s ‘right touch’ approach to the Council’s role.

Reed also says progress during her time is partly a matter ‘of everything in its time’ as often innovation and change – like the introduction of the nurse practitioner (NP) in 2001 – initially causes resistance that reduces over time.

“Sometimes you have to bring in new roles or policies with a tight rein on them to reassure the public and others (like some in the medical profession) that there is not a public safety risk. And then you can evaluate them after a few years and say we don’t need to have such high surveillance,” says Reed.