LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Reading and reflecting on this article will enable you to:

- The nurse will describe a quick and opportunistic screening method to detect atrial fibrillation in patients who are asymptomatic.

- The nurse will feel more confident in providing health information and advocating for patients with atrial fibrillation, regardless of their practice setting.

Study shows nurses make a difference in AF

Nurse-led care for patients with atrial fibrillation has been shown to be superior to the care of cardiologists in improving adherence to guidelines, a decrease in cardiovascular death and a trend toward decreased hospitalisation8. This is not really surprising as there is a well-established body of evidence that nurse-led care is equivalent to or better than care provided by doctors for managing many chronic conditions9.

No matter where you practice nursing, chances are, if you work with adult patients, you will care for someone with atrial fibrillation. It is estimated that by 2036 about 6.5 per cent of Australians aged 55 and older will have atrial fibrillation1,2. The incidence of atrial fibrillation is estimated at between one and two per cent of the adult population and is increasing in

No matter where you practice nursing, chances are, if you work with adult patients, you will care for someone with atrial fibrillation. It is estimated that by 2036 about 6.5 per cent of Australians aged 55 and older will have atrial fibrillation1,2. The incidence of atrial fibrillation is estimated at between one and two per cent of the adult population and is increasing in

New Zealand, as it is elsewhere, and may be due to more than just the ageing of the population3,4.

While atrial fibrillation itself is rarely fatal, it carries a fivefold increase in risk of stroke, as well as increased risk of heart failure4. These conditions have significant impact on the life of the affected patients. Christensen and colleagues found that the 30-day mortality risk for New Zealand stroke patients who also have atrial fibrillation was 20 per cent. That’s a lot of patients with a potentially preventable problem.

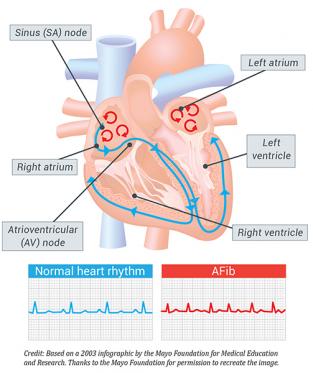

What is atrial fibrillation?

Atrial fibrillation is characterised by the loss of the sinus node impulse in the normal cardiac cycle. The sinus node is the heart’s natural pacemaker and initiates each beat in the normal heart. In atrial fibrillation, this is replaced by rapid and irregular atrial impulses. This leads to an irregular pulse as the atrial impulses are irregularly conducted through the AV (atrioventricular) node to the ventricle. This is illustrated in the figure below.

Some AF patients may have symptoms such as palpitations or ‘skipping’ beats and may feel short of breath or tire easily, while others don’t have any symptoms at all, making it very difficult to diagnose. Patients can experience a single episode of atrial fibrillation or many short episodes (paroxysmal atrial fibrillation) and some are permanently in atrial fibrillation (chronic atrial fibrillation). The incidence of atrial fibrillation increases with age and in conditions such as uncontrolled hypertension, valvular heart disease, sleep apnoea, excessive alcohol and diabetes mellitus. Heart failure can both cause and be a result of atrial fibrillation. Increasingly, obesity is being implicated as a risk factor for atrial fibrillation1,7.

There are a few key points that can help nurses to provide the best care for their patients. The foundation of treatment of atrial fibrillation is stroke prevention and heart rate control.

The European Society of Cardiology recommends opportunistic screening for atrial fibrillation in asymptomatic patients by simple pulse taking. If the pulse is irregular, an ECG should be done to identify the rhythm. This would then identify a significant number of asymptomatic patients with atrial fibrillation and who are at risk of stroke.

Preventing stroke is a key focus of AF patient care

The high risk of stroke is a major focus of the care and treatment of people with atrial fibrillation. The European Heart Journal guidelines suggest anticoagulation with an oral anticoagulant, such as warfarin or dabigatran for all patients who are not low risk4.

Any patient with valvular heart disease and atrial fibrillation should be anticoagulated with a goal INR of 2.0–3.0. (INR, the international normalised ratio, is the gold standard test for anticoagulation with warfarin. If the patient is on dabigatran, INR is not needed.) However, if they also have a prosthetic heart valve, INR recommendations are determined by the type of heart valve they have received.

For all other patients, the need for anticoagulation is determined by their risk level for stroke. Aspirin alone is not effective in stroke prevention unless the patient is low risk4.

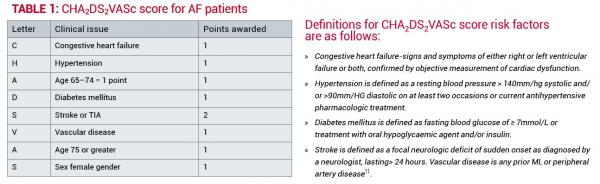

The CHADS2 score was developed in the early 2000s to determine who is at increased risk of stroke and has been recently re-evaluated and modified as the CHA2DS2VASc score. The CHADS2 and CHA2DS2VASc scores are designed to derive a point score for patients to evaluate risk for stroke or other thromboembolic events. Table 1 shows how the score is derived.

A CHA2DS2VASc score of 0 is considered low risk where a decision not to anticoagulate is appropriate12.

A CHA2DS2VASc score of 0 is considered low risk where a decision not to anticoagulate is appropriate12.

A score of 1 is regarded as moderate risk and the benefits of anticoagulation or anti-platelet treatment will be assessed.

A score of 2 or more is considered high risk for stroke and anticoagulation with warfarin and, in selected patients, dabigatran must be considered4,11,12.

Balancing the risks and benefits of anticoagulation therapy

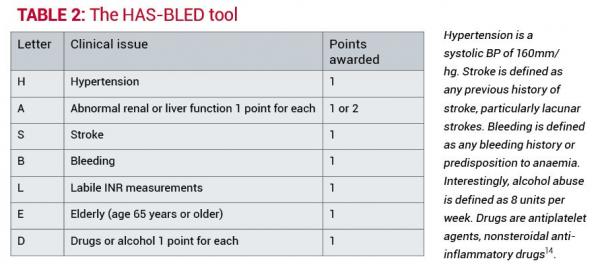

Anticoagulation, though beneficial, carries the risk of bleeding, which can range from simple cuts to major bleeding into the brain or the gastrointestinal tract. The HAS-BLED tool has been shown to be better at predicting bleeding than previously developed tools13. This was developed to assess the potential for significant bleeding versus the potential benefit of stroke prevention. Table 2 outlines how the HAS-BLED score is calculated.

The HAS-BLED score has been validated in several studies and is predictive of intracranial haemorrhage15. In determining the risk of bleeding in an individual patient, care must be taken to understand what the risk implies for a particular patient.

For example, a HAS-BLED score of 3 or more is indicative of caution needed with anticoagulation and also the need for regular review if anticoagulated. A high score should indicate the need to consider any strategies for reducing the risk of bleeding by assuring hypertension is well controlled, cessation of aspirin or other NSAID therapy, or more frequent review of patients with labile INR readings12.

All of this needs to be carefully explained to the patient so that they can make an informed decision on whether they wish to carry the increased risk of bleeding or the increased risk of stroke. A well-informed patient will also be more likely to report any concerning symptoms and follow recommendations for medication management and blood testing16

More about the drugs used to manage AF

Warfarin works by interfering with the synthesis of vitamin K-dependent clotting factors in the liver (e.g. Factors II, VII, IX and X). As a result, it is difficult to determine the exact dose of warfarin required by an individual patient as diet and other issues will alter the level of vitamin K in the body.

The patient needs a diet that has a consistent amount of vitamin K, for example eating one serving of green leafy vegetables every day.

Dabigatran is a useful drug, and patients do not need frequent blood testing. They do need to be aware of signs of bleeding and to seek medical advice if they have any signs of bleeding.

Many patients with atrial fibrillation are managed with medication to control the heart rate and anticoagulation to reduce the risk of stroke. Some patients have significant symptoms, including shortness of breath and decreased exercise tolerance and may need referral to a cardiologist to attempt rhythm control.

Cardioversion, a procedure to restore normal sinus rhythm, can be attempted if a patient is adequately anticoagulated prior to the procedure (well-documented INR readings above 2 for a minimum of three weeks prior to the procedure is the most common). Nurses in primary care may be asked to work with patients to ensure that they have adequate anticoagulation prior to the procedure and in the weeks following. The patient is at the highest risk of stroke following a cardioversion in the first three weeks after the procedure. Most recommendations are for patients to be anticoagulated for a minimum of four weeks following a successful cardioversion4.

To achieve heart rate control, there are several options in drug therapy.The choice will depend on patient factors. Beta blockers are a useful group of drugs and metoprolol is a good choice for rate control. Beta blockers may sometimes cause side effects such as depression or make the detection of hypoglycaemic episodes challenging and so are not appropriate for every patient.

Calcium channel blockers such as verapamil and diltiazem are useful for rate control, but are contra-indicated in patients with heart failure or an ejection fraction less than 30 per cent.

Digoxin is useful for rate control in patients with heart failure. Care must be taken to avoid digoxin toxicity. The symptoms of digoxin toxicity are subtle and include nausea and visual disturbances such as blurred vision and yellow-green halos. Careful monitoring is needed to avoid toxicity as it can cause heart arrhythmias17.

Putting theory into action

The following AF patient scenarios are common and it is important to have a good understanding of the condition to assure that you are promoting the best care for your patients.

CASE STUDY ONE

You start your shift and measure the pulse of a 75-year-old man who is three days post-op following a NOF (neck of femur) fracture. You notice that his pulse is irregular and rapid. Also the pulse oximeter is having a difficult time with the oxygen saturation measurement. The patient feels slightly short of breath and has never noticed an irregular pulse previously. He has a history of hypertension. You obtain an ECG and see that he is in atrial fibrillation with a heart rate of 128. His blood pressure is 128/78mm/hg.

The treatment priorities for this patient would include heart rate control, as a heart rate of greater than 100 beats per minute is associated with the development of heart failure if maintained for more than a few days. You would want to see if the patient had previously been on a heart rate controlling medication, such as a beta blocker like metoprolol, or a rate-controlling calcium channel blocker like diltiazem. If so, have they been resumed post-operatively? What is the patient’s blood pressure? Will it tolerate a blood pressure lowering medication such as a beta blocker or a calcium channel blocker? All of this needs to be discussed with the patient’s doctor or nurse practitioner and appropriate treatment started.

Many patients who experience atrial fibrillation in the post-operative setting have only transient atrial fibrillation and revert back to their normal rhythm in a few days. These patients are at higher risk for recurrent atrial fibrillation, but the decision regarding anticoagulation will need to be made following further evaluation by either the GP or a cardiologist. If the patient remains in atrial fibrillation for more than 72 hours, consideration will need to be made for longer term anticoagulation.

To assist in the recommendation for anticoagulation, you can calculate the patient’s stroke risk by using the CHA2DS2VASc score. As he is a post-operative patient, this is a complex decision. Most patients who are post-operative from a hip joint surgery are prescribed some form of anticoagulation to prevent DVT. When assessing which anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation is required, you will need to take into consideration the risk of bleeding from the recent surgery, in addition to the HAS-BLED score. Discussion with the patient’s doctor about anticoagulation will also be necessary, along with recommendations for follow-up with the patient’s GP.

CASE STUDY TWO

You are a practice nurse in a busy practice. Your GP asks you to follow up with Mrs J as her INR is 3.8 and is too high. You put her on your list of patients to ring today. She is a 68-year-old woman who has had atrial fibrillation for three years. She had rheumatic fever as a child. You notice that she has had very few INR levels within the recommended range of 2.0-3.0 and her warfarin dose has been changed frequently. When you ring her, she tells you of her plans to go to Australia to visit her son and wonders if there is an alternative to this warfarin and all these INR checks. You assess her CHA2DS2VASc and HAS-BLED score. Can this patient be changed to dabigatran as this medication does not require frequent INR measurements?

This is an important question. It depends on whether she has valvular heart disease as a result of her rheumatic fever as a child. Any patient with valvular heart disease and atrial fibrillation has a high risk of stroke and needs anticoagulation. Dabigatran is a useful drug as it does not require blood testing for monitoring and is safe for patients with good renal function (GFR greater than

30mL/min/1.73 m2). It is important to note that it is not approved for use in patients with atrial fibrillation and valvular heart disease.

Despite the challenges, it would not be recommended to change this patient to dabigatran. She should remain on warfarin and you will need to assist her in finding a lab to have her INR drawn in Australia while she is there. You will also want to schedule some time with her to assess why her INR has been labile and to see if you can help her gain better INR control.

CONCLUSION

While these cases might seem very different, they outline the issues that are common to anyone with atrial fibrillation. First, heart rate control is very important in the care of patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart rates over 100 bpm are associated with an increased risk of heart failure. Secondly, atrial fibrillation carries a risk of stroke in most patients. Those at risk can be identified and treatment can be undertaken to minimise the risk of stroke, as well as the risk of bleeding.

About the author:

Sandra Oster RN, MSN, is a professional teaching fellow at The University of Auckland. Prior to coming to New Zealand almost six years ago, she was a hospitalist nurse practitioner at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, USA.

This article was peer reviewed by:

- June Poole RN, MN, a nurse practitioner (cardiology) at Middlemore Hospital for Counties

Manukau District Health Board - Amanda McCracken RN, MHSc, a nurse practitioner (primary health care) for

Southern Nursing Services.

Recommended reading:

- BANG A & MCGRATH N (2011). The incidence of atrial fibrillation and the use of warfarin in Northland, New Zealand stroke patients. The New Zealand Medical Journal 124(1343)

- BPAC (2011) Management of atrial fibrillation in general practice, Best Practice Journal BPJ: 39 www.bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2011/october/af.aspx

REFERENCES

- MIYASAKA Y, BARNES M, GERSH B, CHA S, BAILEY K, ABHAYARATNA W, et al. (2006). Secular trends in incidence of atrial fibrillation in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1980 to 2000, and implications on the projections for future prevalence. Circulation 114(2):119-25.nursing 34(6) 41-7.

- BALL J, THOMPSON DR, SKI CF, CARRINGTON MJ, GERBER T, STEWART S. (2015) Estimating the current and future prevalence of atrial fibrillation in the Australian adult population. The Medical Journal of Australia;202(1):32-5.

- CHRISTENSEN AL, RASMUSSEN LH, BAKER MG, LIP GYH, DETHLEFSEN C, LARSEN TB (2012) Seasonality, incidence and prognosis in atrial fibrillation and stroke in Denmark and New Zealand. BMJ Open 2(4).

- EUROPEAN HEART RHYTHM ASSOC, EUROPEAN ASSOCIATION FOR CARDIO-THORACIC SOC, CAMM AJ, KIRCHHOF P, LIP GY et al (2010). Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). European Heart Journal 31(19):2369-429.

- HANNON N, SHEEHAN O, KELLY L, MARNANE M, MERWICK A, MOORE A, et al (2010). Stroke associated with atrial fibrillation–incidence and early outcomes in the north Dublin population stroke study. Cerebrovascular Disease 29(1):43-9.

- THRALL G, LANE D, CARROLL D, LIP GY (2006). Quality of life in patients with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. American Journal of Medicine. 119(5):448 e1-19.

- GROGAN M, SMITH HC, GERSH BJ, WOOD DL (1992) Left ventricular dysfunction due to atrial fibrillation in patients initially believed to have idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. The American Journal of Cardiology 69(19):1570-3.

- HENDRIKS JML, DE WIT, R., CRIJNS, H. J. G. M., VRIJHOEF, H. J. M., PRINS, M. H., PISTERS, R., PISON, L. A. F. G., BLAAUW, Y., TIELEMAN, RG (2012). Nurse-led care vs. usual care for patients with atrial fibrillation: results of a randomized trial of integrated chronic care vs. routine clinical care in ambulatory patients with atrial fibrillation. European Heart Journal 33:2692-9.

- HORROCKS S, ANDERSON E, SALISBURY C (2002). Systematic review of whether nurse practitioners working in primary care can provide equivalent care to doctors. British Medical Journal 324(7341):819-23.

- GAGE GF, WATERMAM, A.D., SHANNON, W., BOECHLER, M., RICH, M. W., RADFORD, M (2001) Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. Journal of the American Medical Association 285(22):2864-70.

- LIP GY, NIEUWLAAT R, PISTERS R, LANE DA, CRIJNS H (2010). Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the euro heart survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest 137(2):263-72.

- LIP GY (2013) Stroke and bleeding risk assessment in atrial fibrillation: when, how, and why? European Heart Journal 34(14):1041-9.

- ROLDAN V, MARIN F, MANZANO-FERNANDEZ S, GALLEGO P, VILCHEZ JA, VALDES M, et al (2013). The HAS-BLED score has better prediction accuracy for major bleeding than CHADS2 or CHA2DS2-VASc scores in anticoagulated patients with atrial fibrillation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 62(23):2199-204.

- PISTERS R, LANE DA, NIEUWLAAT R, DE VOS CB, CRIJNS HJGM, LIP G (2010). A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: The euro heart survey. Chest 138(5):1093-100.

- OMRAN H BR, RÜBENACKER S, GOSS F, HAMMERSTINGL C (2012). The HAS-BLED score predicts bleeding during bridging of chronic oral anticoagulation. Results from the national multicentre BNK Online bRiDging REgistRy (BORDER). Thrombosis and Haemostasis 108:65–73.

- STREET JR RL, MAKOUL G, ARORA NK, EPSTEIN R (2009). How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician–patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Education and Counseling 74(3):295-301.

- LEXI-COMP (2009) Drug Information Handbook for Advanced Practice Nursing 10th edition, Lexi-Comp, Hudson, Ohio.