By Kylie Hodgson

Learning outcomes

Reading and reflecting on this article will enable you to:

- define cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention of coronary artery disease

- describe the risk factors associated with coronary artery disease

- identify areas where nurses can influence secondary prevention of coronary artery disease for patients

- understand how secondary prevention and cardiac rehabilitation relates to positive client health outcomes.

Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is the leading cause of health loss due to premature death, illness or impairment In New Zealand1.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that 7.4 million people died of CAD in 2012 and that most of these diseases could have been be prevented by addressing behaviour risk factors such as smoking, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity and harmful drinking2.

CAD affects people in all socioeconomic groups, spans a wide range of age groups and continues to be the top cause of death internationally.

CAD is a type of blood vessel disorder that falls within the general category of atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis comes from the Greek athere, meaning ‘gruel’, and skleros, meaning ‘hard’, and it is commonly known as ‘hardening of the arteries’3.

Atherosclerosis begins with the formation of fatty streaks in the artery walls due to endothelial dysfunction, the oxidation of lipids and the development of foam cells (lipid-laden macrophages, which invade the intima and extracellular matrix)3. The fatty streaks eventually develop into deeper, complex plaques, which harden over time and form obstructive lesions in the coronary arteries3. These lesions of fatty plaque narrow the artery vessels, causing angina, or they rupture and form blood clots leading to heart attacks (myocardial infarction)3.

Cardiac rehabilitation

Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) after a heart attack assists the patient to return to normal activities2and make lifestyle changes to reduce their risk of further cardiac events4,5. CR has evolved over the decades into a multidisciplinary approach, including patient education, individually tailored exercise training, risk factor modification and looking at the overall wellbeing of the cardiac patient19. Evidence that CR reduces mortality, morbidity and unplanned hospital admissions – along with improvements in exercise capacity, quality of life and psychological wellbeing – is increasing20. CR is now recommended in international guidelines including New Zealand11,20. A very recent Cochrane Review looking specifically at exercise-based CR programmes for CAD confirmed that exercise-based CR reduces cardiovascular mortality and also leads to reductions in hospital admissions and improvements in quality of life21.

New Zealand’s district health boards have designated nurse specialists in the cardiac field to carry out the CR role and they are often part of a multidisciplinary team that can include a cardiologist, pharmacist, physiotherapist, psychologist, dietician, occupational therapist and social worker5. CR has three phases. The first phase starts while the person is in hospital after an acute cardiac event. The second phase is a supervised outpatient programme, usually involving a range of education sessions and an exercise component, which can run over four to 12 weeks depending on location5. Unfortunately, the uptake of CR programmes, both here and internationally, is relatively poor – between 20 and 50 per cent – which has been attributed to referral issues, lack of information, funding issues and travel and time concerns19,20,22. Nurses can have a role in increasing the uptake of outpatient programmes by being well informed about CR and encouraging patients to take up referrals20,22.

The third phase of CR follows on from the outpatient CR programme and is carried out by the patient’s primary healthcare team (their GP, nurse practitioner or practice nurse), who assist the patient with secondary prevention of CAD and the long-term management of the condition5.

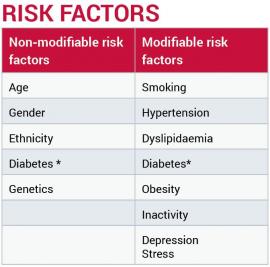

Knowing the CAD risk factors is key

All registered nurses – whether they are working in the cardiac field or as practice nurses, or any other nurses coming into contact with patients with known CAD – should be able to assist in secondary prevention of CAD. Knowing the risk factors for further cardiac events is very important if nurses are to support patients to modify their lifestyles and reduce the impact of these risk factors.

Risk factor management of CAD and continued medication adherence are the key focus areas in the cardiac rehabilitation guidelines for secondary prevention5,6.

How much patients move, what they eat and whether they smoke are all important factors that influence a person’s risk of heart disease4,6. When discussing risk factors, it is important to understand how they impact on CAD and relate this to each individual’s situation4,5,7.

Definitions

Cardiac rehabilitation is the “coordinated sum of interventions required to ensure the best physical, psychological and social conditions so that patients with chronic or post-acute cardiovascular disease may, by their own efforts, preserve or resume optimal functioning in society and, through improved health behaviours, slow or reverse progression of disease”5.

Secondary prevention is defined as “the long-term management of people who have existing cardiovascular disease, have had a cardiovascular event, have had a cardiovascular surgical procedure and are at risk of a cardiovascular event”6. Secondary prevention is evidence-based guidance on how to reduce the incidence of recurrent cardiac events due to CAD6.

CAD risk factors

Smoking: Smoking increases the risk of heart disease by two to four times over those who are non-smokers4. Smoking impacts on endothelial dysfunction due to cellular changes caused by the toxins in cigarettes3. The nicotine increases the workload on the heart by stimulating the heart rate, increasing blood pressure (BP), causing vasoconstriction and impeding oxygen supply5. There is a transient rise in BP with each cigarette, in those who smoke more than 15 per day but, interestingly, habitual smokers generally have a lower BP than non-smokers, possibly due to lower body weight8.

Hypertension: A BP of greater than 140/90mmHg affects the endothelium by pumping blood through the vascular system at force; there is a shearing effect and this increases the risk of coagulation and also increases lipid infiltration3.

Dyslipidaemia (abnormal blood lipids): This involves an increase in low density lipids (LDL) and/or the ratio of total cholesterol to high density lipids (HDL) in the blood. These two types of lipids are sometimes referred to as good (HDL) and bad (LDL) cholesterol9. The LDL infiltrate the arterial lining and are a factor in the formation of atherosclerosis3,4. The HDL removes LDL from the artery walls3,9 and transports it back to the liver in a process known as reverse cholesterol transport. Triglycerides are the main storage form of lipids and when raised are associated with CAD3.

Diabetes: People with diabetes (both type 1 and type 2) are two to four times more likely to have CAD4 as it damages the endothelium by increasing inflammation and making infiltration of lipids and clotting more likely3,9. Diabetes is non-modifiable in its diagnosis, but glycaemic control is modifiable and good control can improve patients’ mortality and morbidity risks4. Early detection and management of pre-diabetes may result in the delay of the onset of diabetes.

Obesity: ‘Globesity’ or global obesity is a worldwide epidemic9. Obesity affects the workload of the heart due to a bigger body mass, as there is a greater demand on the myocardial oxygen demands to meet the supply3. The mechanism of hypertension in obesity is not fully understood, but is associated with central (abdominal) obesity, and hyperinsulinaemia, which may impact on the sympathetic nervous system and increase the risk of sleep apnoea10. Obesity puts a person at greater risk of hypertension, and hence the increased risk of atherosclerosis10.

One of the impacts of obesity is the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome, which increases the risk of developing CAD9,10. Also, due to higher energy stores of fat in the body, the body shuts down its use of glucose for energy, and insulin receptors are reduced, making patients insulin resistant and at a higher risk of type 2 diabetes3.

Inactivity: This impacts on a multitude of factors, namely cardiovascular fitness, blood pressure, lipid levels and weight9. Being active increases cardiovascular fitness, reduces blood pressure over the long-term, increases HDL cholesterol and assists in either losing or stabilising weight. The Cochrane Review found that CR programmes that included structured aerobic exercise programmes led to a reduction in cardiovascular mortality and the risk of hospital admissions, and also to an increased quality of life21.

Stress and depression: The stress that impacts on CAD is long-term stress that is difficult to cope with4. For example, relationship stresses, financial stress, death in the family. Stress of any kind, short or long-term, releases the hormones cortisol and adrenaline, which impact on the workload on the heart and increase the risk of hypertension and the shearing force and damage to the endothelium3. Persistent levels of cortisol increase deposits of abdominal fat, and stress may cause an increase in adrenalin, which may both, in turn, influence a raised BP12. Stress promotes the progression of atherosclerosis, inflammation and endothelial dysfunction and accounts for approximately 30 per cent of the population’s attributable risk of acute MI19. Stress in the long-term may lead to depression and depression increases the risk of mortality5. Depression, anxiety and denial occur in up to 20 per cent of patients following myocardial infarction19. Psychosocial assessment should be done on all patients post-cardiac event and support offered as required5.

Lifestyle modifications

The nurse’s role is to educate patients and their whānau on what risk factors are modifiable and how these risks can be reduced7. Nurses need to communicate clearly with patients by firstly discussing and acknowledging what the patients regard as their risks and then by raising other risk factors that should also be considered4,5,7. All lifestyle modifications should be tailored to meet the individual’s needs and the patient’s social and financial responsibilities should be taken into consideration when discussing ways to reduce their risk factors5,7,13. Engagement of the patient and their whānau is pivotal to any lifestyle change4. The patient must also acknowledge that there is an issue and then want to change, for any success to occur. Successful lifestyle modification does not always require massive change as small differences can have a big impact on health outcomes in the long term4. Having the support of a patient’s whānau has a major impact on the success of any lifestyle change and nurses can help facilitate that4,7. For example, encouraging the involvement of spouses and/or adult children or other family members in discussions about lifestyle changes, such as the need to eat differently, exercise more, adhere to medications and stop smoking14,5,7. Encouraging family to attend the education component of phase two CR programmes is a good way to do this.

Medications

Adherence to medications is another major factor in secondary prevention of CAD5,6. Cardiac medications are paramount in reducing mortality and morbidity; they are lifelong and for many patients constant medication adherence is a struggle to achieve14,15. Patients and their whānau need to be informed of the benefits of taking medications and nurses need to support patients to make an informed decision about treatment4,5.

Secondary prevention by cardioprotective medication adherence decreases the risk of another cardiac event by 25–30 per cent in five years if taken correctly16. The WHO identified that medication adherence among patients with CAD, along with smoking cessation, reduces the risk of a future event by 75 per cent2.

This area is one in which nurses can make a big difference by discussing with their patients during each interaction the importance of adherence to their cardioprotective medications. Assessment of medication adherence is important; if there is an issue, nurses should ascertain the reasons, for example, cost, concern about side-effects or difficulties with remembering to take their medications. Some strategies to improve medication adherence could include:

- providing information about family prescription subsidy cards

- liaising with a community pharmacist

- offering individualised medication education to reflect patients’ health literacy levels

- asking patients what time of day they would prefer to take their medications

- looking at options like blister packaging, smartphone alerts and drug diaries to help people to remember to take their medications regularly

- setting goals for medication adherence supported by regular follow-up, feedback and positive reinforcement14,15.

Goals need to be SMART

Secondary prevention is not about being ‘the poster child for heart disease’ and doing everything right for six months then lapsing back into old ways. If this happens, any reduction in risk is lost and gone.

Goals need to follow the SMART acronym4,7:

Specific: target a specific area for improvement Measurable: quantify or at least suggest an indicator of progress Achievable: is it feasible?

Realistic: state what results can realistically be achieved, given available resources Time-bound: specify when the result(s) can be achieved.

The SMART goal format is used to discuss lifestyle change with patients and their families, to give the goals context and to help set parameters for achieving these goals. Lifestyle modification is not about ‘pointing the finger’ at a patient’s issues but rather about discussing the risk factors and allowing the patient to decide what is important for them to work on and then assisting them to achieve it4. Any lifestyle change needs to be in collaboration with the individual and their whānau, as this increases the likelihood of a long-term successful lifestyle modification4,7.

Case Study

Mr X, aged 60, has been a smoker for 40 years, is overweight and has a sedentary lifestyle.

Mr X stops smoking, using smoking cessation aids. Long term, this significantly reduces his mortality risk and his potential for a recurrent cardiac event5,6,8,9. He is still overweight and has a sedentary lifestyle, which means he remains in the ‘at risk’ category5,6,11. But successful lifestyle modification does not tackle all risk factors at once and instead lets the patient themselves decide which is best to address first4,7.

Case Study

Mr Y, aged 46, is a father of five school-age children and is a factory worker who exercises rarely.

Regular exercise, as discussed on the New Zealand Heart Foundation website4, is a great investment in secondary prevention as it has a positive impact on weight, blood pressure, cardiovascular fitness, stress, and diabetes control. Thirty minutes a day for an adult is recommended9 but due to lifestyle commitments, this is sometimes difficult to achieve. Exercising in chunks of 10 minutes at a time will still be beneficial and in some cases more achievable4. In New Zealand we have available green prescriptions17, which a nurse or GP can prescribe to help support a patient and their whānau to achieve a healthier lifestyle through taking part in regular exercise. There is no point in encouraging a father of five on the minimum wage to join a gym to improve his cardiovascular fitness if that is not financially viable for him or his whānau. Health professionals need to work in collaboration with the patient to find an appropriate exercise intervention that is likely to be successful in the long term.

Conclusion

Secondary prevention has a major impact in reducing future coronary events4,5,6,13,18. The aim is for the patient to return to their daily living activities with an understanding of their condition and having instigated lifestyle changes that will best reduce their risk of further events5,6,13.

Adopting a whānau-based approach to secondary prevention means health professionals can influence not only the individual but also their wider family following a cardiac event4,7.

Secondary prevention reduces mortality and morbidity, reduces hospital admissions and reduces costs to health care6,9.

All nurses involved in the care of patients with coronary artery disease can influence secondary prevention. By acknowledging and discussing the potential risk factors during each patient interaction, and by assessing patients’ medication adherence, nurses can have a positive impact on long-term patient outcomes.

Download the learning activity here>>

About the author:

Kylie Hodgson RN PGDip is a University of Auckland professional teaching fellow and is studying for her master’s degree in health. Her last clinical post was as clinical nurse specialist in cardiac rehabilitation at Auckland City Hospital.

This article was peer reviewed by:

Andrew McLachlan, NP Adult Cardiology at Counties Manukau DHB and chair of the New Zealand Rehabilitation and Secondary Prevention working group of the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand.

Brigitte Lindsay, NP Adult Cardiology, has worked in cardiology for 21 years (eight as an NP for the Taranaki District Health Board) and now also works in general practice.

Further resources and recommended reading

BMJ Clinical Review of Cardiac Rehabilitation (September 2015)

www.bmj.com/content/351/bmj.h5000

New Zealand Heart Foundation

www.heartfoundation.org.nz

Health Navigator. New Zealand website offering health information and self-care resources

www.healthnavigator.org.nz

References

- 1. Ministry of Health (2014). New Zealand Burden of Diseases, Injuries and Risk Factors Study, 2006–2016. [Online] www.health.govt.nz (accessed 18 January 2016)

- 2. World Health Organisation (2015). Cardiovascular diseases Fact Sheet [Online] www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs317/en (accessed 18 January 2016)

- 3. Brown D et al (2014) Lewis’s medical-surgical nursing: assessment and management of clinical problems

- (ANZ 4th edition). Elsevier, Australia.

- 4. New Zealand Heart Foundation (2015). Heart Help First Steps.[Online] http://firststeps.hearthelp.org.nz

- (accessed 18 January 2016)

- 5. New Zealand Guidelines Group (2002) Cardiac rehabilitation guideline. Ministry of Health. [Online] www.heartfoundation.org.nz/uploads/guidelines_summary(2).pdf (accessed 18 January 2016)

- 6. World Health Organisation (2007). Prevention of cardiovascular disease. [Online] www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/guidelines/Pocket_GL_information/en

- (accessed 18 January 2016)

- 7. Best Practice Advocacy Centre New Zealand (2014) Communicating cardiovascular risk effectively.

- Best Practice Journal 63

- 8. Kaplan N et al (2015) Smoking and hypertension. UptoDate. [Online] www.uptodate.com (accessed 18 January 2016)

- 9. World Health Organisation (2011). Cardiovascular disease: Global atlas on cardiovascular disease prevention and control. [Online] www.who.int (accessed 18 January 2016)

- 10. Kaplan N et al (2015) Obesity and weight reduction in hypertension. UpToDate. [Online] www.uptodate.com

- (accessed 18 January 2016)

- 11. Ministry of Health (2012), New Zealand Primary Care Handbook 2012 www.health.govt.nz

- (accessed 18 January 2016)

- 12. New Zealand Heart Foundation (2016). Stress and the Heart. [Online] www.heartfoundation.org.nz/healthy-living/managing-stress/stress-and-the-heart

- (accessed 18 January 2016)

- 13. Alm-Roijer C et al (2004) Better knowledge improves adherence to lifestyle changes and medication in patients with coronary heart disease. E

- uropean Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing 3.

- 14. Brown M & Bussell J (2011) Medication Adherence: WHO cares. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 86(4)

- 15. Bosworth H et al (2011) Medication adherence:

- A call for action. American Heart Journal 162 (3).

- 16. Health Quality and Safety Commission (2015)

- Atlas of Healthcare Variation: Cardiovascular Disease. [Online] www.hqsc.govt.nz (accessed 18 January 2016)

- 17. Ministry of Health (2014). Green Prescriptions. [Online] www.health.govt.nz

- (accessed 18 January 2016)

- 18. Griffo R et al (2013) Effective secondary prevention through cardiac rehabilitation after coronary revascularisation and predictors of poor adherence to lifestyle modification and medication.

- International Journal of Cardiology 167

- 19. Mampuya W (2012) Cardiac rehabilitation past, present and future: an overview, Cardiovascular Diagnosis and Therapy 2 (1)

- 20. Dalal M, Dohert P & Taylor R (2015) Clinical Review: Cardiac rehabilitation, British Medical Journal 351:h5000

- doi: 10.1136/bmj.h5000

- 21. Anderson L, Oldridge N, Thompson D et al (2016) Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease (Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis) , Journal of the American College of Cardiology 67 (1)

- 22. Hutchinson P, Meyer A & Marshall B (2015) Factors influencing outpatient cardiac rehabilitation attendance, Rehabilitation Nursing 40(6)